Not my style?

Man! The world will end

And you complain.

I want to do

The things I have not done

Not just taste the nectar of the gods

But drown in it too.

Shed my grass-root skin.

Emerge!

A woman!

poet!

writer!

musician!

Kathleen Jean Mary Ruska

Kath Walker

Oodgeroo Noonuccal

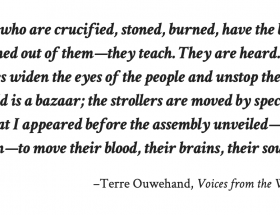

It’s almost ironic that a woman with so many names would become so instrumental in the articulation of identity. As a writer and educator, Oodgeroo Noonuccal expressed an indigenous female narrative that was previously unrepresented and unheard in English literature. Her impact on the First Nations people of Australia, especially those of her fellow Noonuccal people, is immortal. The tools of her activism, her poems, ring haunting truth of the Indigenous Australians’ plight even today. Beyond this, her excellence as a writer and educator not only won her national literary accolade, but recognition from universities abroad.

Above all, she was brave and independent. She would not allow her own voice to be compromised. She helped ensure the continuation of her cultural legacy. And yet, there is a note of melancholy that resonates throughout her writing; a fear that, despite her efforts, an ancient culture will be eclipsed by an unconcerned nation.

Born on Stradbroke Island in the year 1920, Noonuccal only attended school until the age of 13 before she left to become a domestic servant in Brisbane. Many indigenous women were subjected to such jobs with low wages and poor treatment, but in 1941 she was able to find a way out by enlisting in the Australian Women’s Army Service.

In the aftermath of World War II, the Australian government sought European emigrants to Australia, but in accordance with the White Australia Policy denied the legal immigration of Asian and non-white refugees. Noonuccal became invested in the cessation of this policy, joining the only party in its opposition; the Communist party of Australia. This period in her life was vital in developing her voice as a public communicator; particularly in regard to public speaking and writing. In this, she excelled and soon was approached to give speeches and represent the party. She declined, claiming that ‘they wanted to write my speeches’ and was instead supported by fellow writer James Devaney, who sent her own prose and poetry to be published with Jacaranda Press. In 1964, Australia’s best-selling poet was raising two sons as a single mother, having returned to domestic work to support her family.

This groundedness and realness was what people admired most about her poetry; it was simultaneously accessible and beautiful, a celebration and a protest. Her influence was instrumental in the Indigenous fight for voting rights and citizenship, and cultural conservation.

After these rights were granted, Noonuccal spent time travelling and lecturing at universities and conferences around the world. She famously survived a plane hijacking on a flight home from Nigeria, documenting the experience in two poems on the back of an airsickness bag. Perhaps her most culturally significant legacy, however, is the establishment of a cultural learning centre in her home. Over the years she met over 26 000 children in a school she called Moongalba; a ‘sitting place’, teaching them about Aboriginal culture, the balance of nature and encouraging them to see the world ‘colour blind’. Indigenous and non-indigenous children were all welcomed.

In Australia, institutions such as these still hold extreme importance. Once, over 500 nations with distinct nationalities, dialects and cultures lived in harmony on the land. Only 145 of these languages are still spoke, and many of these nations are extinct or critically endangered. Figures such as Noonuccal valiantly light the way for these cultures to be preserved, recognised and understood by us, who now coexist with them. But change is not coming quickly enough. Twenty-six years after Noonuccal’s death in 1993, Indigenous Australians still largely exist in a liminal space within our societies. It’s time to listen and understand before their narratives disappear altogether.

The scrubs are gone, the hunting and the laughter.

The eagle is gone, the emu and the kangaroo are gone from this place.

The bora ring is gone.

The corroboree is gone.

And we are going.