DONT WALK: A Review

My toy Pegasus came with me that night, for anxiety reasons. Their name is Telepathy. We’re best friends.

Now, if you’ve ever dealt with psychic fantasy creatures, you’ll know they’re great at reducing stress, lowering blood pressure, being freaking cute, and chasing away the flashbacks. “This’ll be the best. Night. Of my entire. Life! Right Telepathy?”

“Preep preep,” said my psychic Pegasus, and I couldn’t agree more. I was going to Don’t Walk now, wasn’t I? So what could possibly go wrong?

The year is 2120. The surface of the Earth is blind with rage. It heaves, and a pall of fracturing steam jumps fussy into the air, pressing its soft scream across a pale, ashen landscape. A cloud of methane steps upwards, slowly reaching toward a slimming rim of blue—and when it ignites the firestorm spirals into the sky, clapping against a ceiling of lightning that lashes its legs against the skirt of space. A sharp wind cuts through the gas plume, spilling over the wastelands of Fife. If we were alive, we’d hear a hundred human screams lagging under the crowded air, hocking up a cry for their mothers, cursing them. Why. Why did you let this happen. When a curtain of yellow gas parts between the shriveled arms of the dead alder trees, a bubble pops in the brine, and the night brings a calmer, darker hush. Four hoofs are on the edge of the salt. Is it—yes. It’s Telepathy.

Telepathy stands on the shores of Pittenweem. They are on their way to where it all began, where the environment was forsaken, once and for all, in the name of student fashion. They are on their way to Bowhouse. They are crying for us. For all of us.

The story goes that for a hundred-hundred years, Don’t Walk has systematically bullied the nerds of St Andrews with its reputation as an exclusive, invite-only event, where the

icy-hottest of the St Andrews glitterati gather to luxuriate in the collective relief of the beautiful, the chosen, the socially transcended.

So it felt great to not only be on the other side of that relationship for once, but in the center of it. As a member of the press, I didn’t receive a tote bag—though what I did receive was much more valuable: a corporate pass.

Here, the word ‘corporate’ intrigued me. It suggested a clandestine enclave of mythical organizers of which I was now a part of, and the pass gave me unlimited access to the haute-est corners of the Don’t Walk èxpèrieèncè. Before the runway began, I joined some of these corporate goons for a séance above the stage, where we beheaded a talking goat and drank its blood with Appletiser, and then all of us made out. Amazing.

“You’re not going to write a bad review?” asked my friend Ania, wiping the blood from her face. This year, Ania was a creative director for Don’t Walk, and one of my closest friends—which in theory should put me in a compromised position as a reviewer until I remind myself that everyone knows everyone in this Jane-Austen-ass town.

“Thank you for the blood,” I said with a princess smile, dipping away. When I looked over my shoulder, the Don’t Walk committee was glaring at me, drawing satanic circles in the air with their fingers, spewing black smoke from their eyes. Nerves, I thought. Nothing personal. “We need some air, sis,” I whispered into the eye of Telepathy’s mind.

“Rah-tah-tah-tah,” said my psychic Pegasus. Brilliant. Fucking genius.

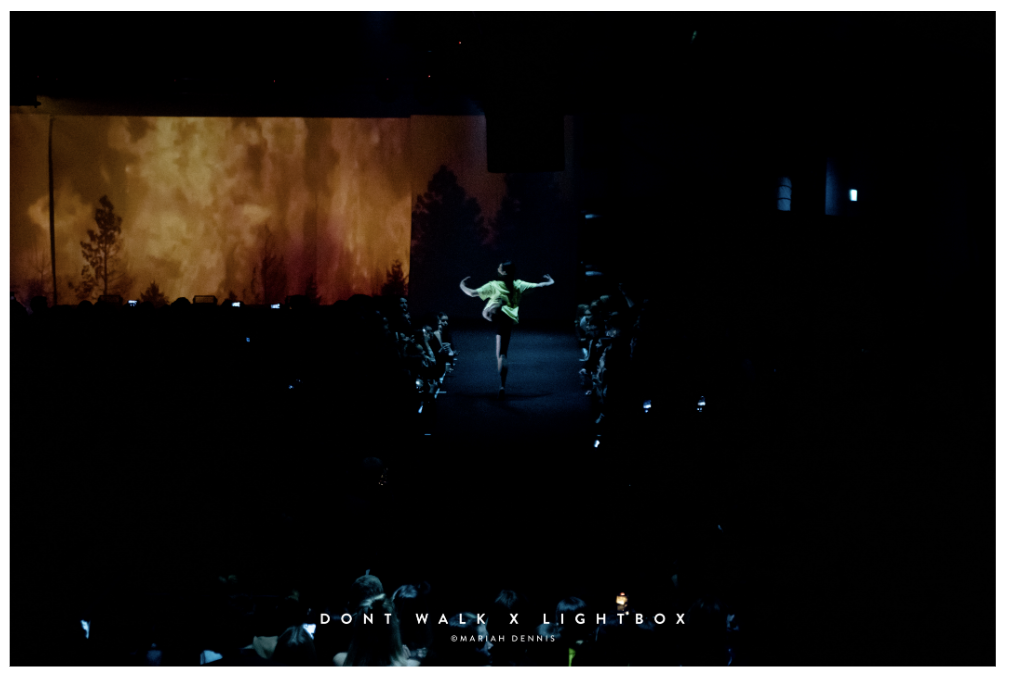

Exploring the venue, it was clear that a lot of effort had gone into transforming the place. Bowhouse is known for its market weekends, where farmers and traders can sell their local produce at a collection of stalls in a rustic, down-to-earth setting. It’s where the people of Fife reconnect with their locality, their indigenous marketplace, a parochial haven for a more homespun agricultural community. There’s some irony then that we’ve staged Don’t Walk here. St Andrews represents both one of the wealthiest, and one of the most ephemeral communities in Fife—the population sheds away in four-year cycles as new students replace them, bringing a ridiculous flow of international cash that seems at odds with the general quaintness of Fife. In a way then, Don’t Walk feels like a micro-purification of this relationship, as the world of Bowhouse is reconfigured and corseted into a funhouse of Euro-chic opulence. A gateway of blue LED lights led us from the entranceway to the stage area, where a circular catwalk formed outer and inner rings for the guests. The inner ring was, of course, where VIP (and corporate—I knuckle bumped Telepathy) was meant to view the show, and I realized I was looking forward to the moment when I could peer innocently across the catwalk to the non-VIP guests. You made it—but you didn’t make it here.

Entering the inner circle, we walked beneath a section of the stage that was raised to form a bridge. Having been a little disappointed by FS—another fashion show earlier this semester—it was clear that a more imaginative theatrical vision was guiding the show tonight. I was starting to feel relieved. Though perfectly willing, I really didn’t want to write a “bad” review. But I was already feeling the influence of the pageantry, it all felt so celebrity, so A-list, in the words of Cardi B my ass felt soufflé, as though the very act of entering this place had elevated me to the status of something I normally was ready to mock. At FS, we had to crowd against the stage, desperately clamoring for the bread of entertainment, and I could barely even see what was happening. Here, the circular stage provided the guests with something more interactive. The stage wasn’t asking us to gather at its alter, but to gawk around, to turn our heads and follow the action, to include ourselves in the choreography of the runway. And I realized that, despite my dogmatic queerness, my 4th wave feminism and my anti-capitalist pretentions, I was ready to objectify some beautiful people, to lift my chin, to nod in approval or wag my finger—no, yass kween, bring it bitch. As I performed an obligatory pivot, turning in a full circle in the center of the catwalk, I noticed that one of my friends was already getting led out by the bouncers. The show hadn’t even started yet, and they were already cracking down.

“What’s this?” some girl asked me, pointing to the Pegasus on my wrist. I introduced Telepathy—and across the room, my friend was disappearing behind a wall of black fleeces.

“You can look at Telepathy,” I told her, “and think your deepest, darkest insecurity, and they’ll keep it a secret forever.”

“This is Don’t Walk,” the girl said. “We’re all insecure.”

Yeah, I thought. It was the prevailing assumption in the room, all along. Around us, the lights were fading, and darkness fell with a boom.

The year is 2121. Telepathy has waited there for us, watching where the North Sea depletes itself into uneven stacks of luminous saline, churning and freezing and melting again in a splash of torrid air. In the distance, a wild Gyarados mouths the words ‘I hate you’ before closing its eyes and succumbing to death. The hot breath of its body rises with a final tug of its gills, and where the world seems more silent, a quail of monoxides rushes against the shore, breeding a porous swell of heat. Telepathy knows they look personally fabulous, as the airstream parts their hair, billows their mane and twinkles through their dust—but only the raiders will see the Pegasus standing on the shore as they prepare for an attack. The raiders rush down the banks, raising their makeshift weapons, spades and tree branches and Chase Sapphire Preferred Cards. They’re dressed in the latest fashion trends from a hundred years ago. In awe, Telepathy turns, and watches as the monoxide curtain chokes them out. One by one, the humans die of suffocation. Some of them are just children. Pathetic mortals, Telepathy thinks, and a single tear falls down their face. Where the tear lands, a sapling sprouts in the sand, and quickly extinguishes itself.

When Telepathy approaches the corpses, they notice that the raiders are all wearing their wristbands for Don’t Walk. Standard wristbands—non VIP. Losers. They can’t stop crying.

This year’s Don’t Walk theme was sustainability. This was more of an aesthetic than a coherent set of values—but I won’t problematize this. It’s just too easy. Too easy to point out the advertisements for private jets, the ridiculous indulgences auctioned during the intermission, all the flatulence produced from the hot dogs they sold, all the hot breath we released as we danced, and the finger-calories forfeited in sewing those hemlines, when those same calories could’ve been used holding picket-signs in front of Sally Mapstone’s house that say: SWALLOW MY AIR TRAVEL, PLASTIC COUGER. So many ideas. So many alternatives. We are a fallen people.

My boyfriend has a theory that humanity will delay its response to our climate crisis for so long that by the time we’re ready for any real change, the only realistic, sustainable solution will see itself in a form of panicked authoritarianism. Spank ourselves before the Earth does, kind of thing. He calls this theory Eco-Fascism—dramatic, I know, but so is the weather.

His theory triggers in me images of so-called eco-warriors. It’s a cliché echoed by climate-deniers who see totalitarianism in everything to the left of their left pinky-toe. But tree-hugging SJWs are really the least of our worries here. Rather, the problem is that en masse we show no signs of slowing down capitalism’s ghoulish suckers, and by the time we face the music, perhaps the only energy source left with which to organize our society will be desperation, fear—fascism. In this humble reviewer’s opinion, the solution to the climate crisis will have nothing to do with how sustainable some student-run fashion show is, and have everything to do with how we redesign our every day relationship to consumption. Projecting this anxiety onto a fashion show seems to me like low-hanging fruit—both a scapegoat we use to redirect blame from our own lives, and a false comfort into which we can meaninglessly sink our energy while relaxing again into our daily habits. If every single fashion show on the planet eliminated their carbon footprint, would we really be any closer to avoiding climate catastrophe? To be clear, it’s unquestionably a net-total good (blah-blah-blah) that Don’t Walk has (at least in marketing) sought to reduce its waste. But if this brings you any reassurance that ‘things are changing’—well, I’m doubtful. And I can’t help but wonder if such gestures have nothing to do with climate change, and everything to do relieving our obsessive sense of guilt. More than Eco-Facism, I think what worries me is the way we use that climate-guilt as an ingenious coping mechanism—so long as we continue hyperventilating over Don’t Walk and Plastic Straws, we can forget the real work we need done in our day-to-day lives.

With this in mind, absorbing the aesthetic of Don’t Walk 2020 reminded me of my boyfriend’s Eco-Fascist prophecies. There was a sense of techno-sadistic doom as the lights fell, and a glitzy, subjugated militarism to the model’s choreography, like elementals caught and remolded to march in strict formation. It was cool. It was slick. It was immersive—I was immersed! The music directed them in a thrumming strobe, and I was reminded of a Gareth Pugh show, where theatrical portent and expressive stridency create an atmosphere of vibrant danger and sensory oppression. Personally, I wouldn’t have minded being stepped on by a few of the models. Danya. Benji. Some other guy I don’t know.

But the fascism thing is too much drama to be exact here. Instead, I think I’d call Don’t Walk’s 2020 aesthetic Eco-Brutalism. Visually, the show linked the kind of frigid geometry of runway glamor to several different landscapes, both wild and organized, drawing a stark juxtaposition between the stiff, anaesthetized beauty of the models and their knotted, brambly environments. In one photograph, the models stood in single-file on a grassy ridge as though living monuments to their environmental submission. We gave up our freedom—but we kept our beauty. They were standing beneath The Falkirk Wheel, a concrete structure that looks abstracted from utility, some pristine monstrosity of a post-climate utopia.

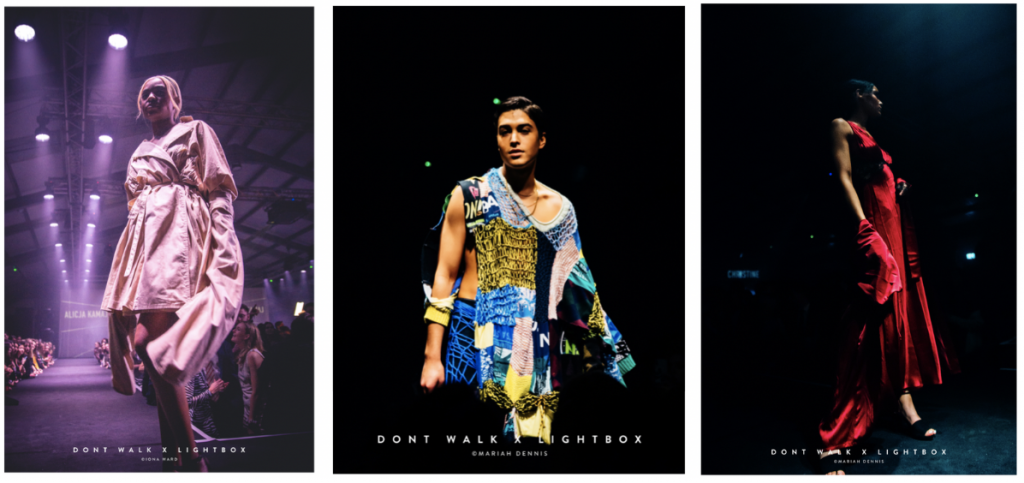

Honestly, I don’t even know that much about fashion, but I thought the clothes were really

neat-o. That hot guy Joey wore this sort of post-apocalypse meets Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat sweater-disaster. Loved it. And that hot girl Elise wore a fungal top that looked like she was being colonized by a floral brain. That was cool. And that other hot guy, French-Matthew, didn’t wear a shirt at one point. I wasn’t angry about that. We can call it fashion.

I met one designer named Beata Karapetyan who had a dress featured in the show that night. When it came out, I saw it had entrails of yarn spun around a red sheer top with vertical stripes, and a bizarre white skirt that looked like a jellyfish tangled in expensive nylon. There was something totally mad about it, totally original. And in total, the fashion told an eclectic, rambling sort of story. Outfits ranged from avant-garde, to very avant-garde, to pajamas, to raincoats, to transparent, avant-garde rain coats, to avant-garde yarn coats, to just nudity, to avant-garde nudity, to some foreplay-on-the-Han-river-realness, hunty (fart noise). But all that’s to be expected at a student fashion show, where sometimes, just getting a single piece on stage can feel like an act of epic heroism—even if we happen to look in the other direction once it’s on the runway. And observing the people around me, I realized as the show drew on that that’s what was happening—that for some people, Don’t Walk was a place to be, rather than an event to witness.

Which— considering the resources pouring into it—was a shame. And I don’t just mean financially, environmentally, socially, politically, astrologically. I mean that I’d just spent two semesters surrounded by Don’t Walk’s creative alliance, who could derail an entire American Horror Story night for some Don’t Walk crises, who practiced their runway jigs during midnight garden parties, who built a fucking fish tank for art to give us dripping wet Danya Bavetta, and who hired international mercenaries to raid Rooney Mara’s closet and steal Joaquin Phoenix’s bottom ribs for some peripheral fashion stunt (which didn’t even make it to the runway cause it didn’t fit the sustainability model, but whatever).

And in the end, they pulled off a kick-ass show. Maybe it was the drugs, but Simona, when you kissed me from the stage, I was crying. So, my friends: Bravo. Or as the Italians say: Bravo.

Telepathy is crying. They remember this place. They remember that night at Bowhouse. When John dragged them around the room, filling their head with the perverted thoughts of Art History majors, local celebrities, European mothers, some guy with five packs of cigarettes. A nightmare. Humans are disgusting creatures, vile, pretentious—where’s the old testament God when you need him? Telepathy’s consciousness is atemporal—and in a spasm of post-trauma they’ve jumped back into the circus. And they look up at John that night. He’s smiling, twirling around like a gutter pixie. “You are murdering the future,” they say.

“You are murdering the future—and you even know it.”

Photographs courtesy of Lightbox via DONT WALK