A strained tension pervades every corner of my home. As Christmas preparations begin earlier and earlier every year, tinsel replacing cobwebs in the local supermarkets in the first week of November, so does my sense of dread. I feel myself holding my breath for longer as the days grow shorter.

Every year my mother cries during Christmas. Not for the reasons you may think, not joyful tears, not tears of reminiscing Christmases past. Her tears are the tears of a woman who at this moment feels like she doesn’t belong, a heavy crushing feeling of being an outsider. This year is more difficult than most, the stress of coronavirus exacerbating the alienation felt on a yearly basis.

As Sephardi Jews, our celebrations are loud and all-encompassing. Our home is awash with colour, from the mismatched plates and cutlery to the plants perching on every available surface. My father goes full-on D.I.Y and constructs a table extension which he modifies every year. Originally held precariously together with clamps, we are now able to rest our elbows on the table extension without fear of it collapsing halfway through dinner. Guests perch on anything we can find – stools, boxes, chairs borrowed from neighbours – piled in our small kitchen, elbows tucked in to avoid winding each other. Not to mention the food, the vibrant dishes that we spend full days preparing, the shared responsibility of feeding guests providing the energy that drives us.

This year we have had to hold all of our holiday celebrations on zoom or alone in our family bubbles. We made it work, we had to. We tried our best with the knowledge that this was necessary, to prevent the spread of the pandemic and protect not just our community but everyone across the globe. There was no relaxation of restrictions so that we could come together for Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah, Diwali, or Eid – and rightly so!

However, just last week we witnessed how the government announced that it was willing to essentially sacrifice people’s lives for Christmas, fully conscious of the fact that cases would no doubt rise as a result. Refute me if I am wrong, but a surge of cases, unavoidably leading to fatalities did not sound very festive, never mind in keeping with the ‘Christmas spirit’. Although this position was revised a couple of days ago– leading to a sudden U-turn whose economic and emotional impact on those celebrating is of undeniable magnitude, the fact still remains that for a while the government had broadcasted two realities. One being the blatant lack of consideration for those on the front line who are pushing themselves to breaking point to save lives and whose job has not been made easier by government policies. The second being that for a while, the government invariably demonstrated huge double standards that served only to remind all who do not celebrate Christmas, that we are outsiders.

This feeling of being an outsider is both experienced and inherited. With respect to experience, this usually comes in the form of suspicion and judgement for not being caught up in the holiday spirit. The constant apprehension of having to face derision and ridicule if we show ourselves to be unfamiliar with certain Christmas traditions. I had my first Christmas leftovers sandwich on Boxing day last year at my ex-boyfriend’s, much to the amusement and disbelief of his family. A moment so small, so unknown to me, that marked me out as other, being told I had not lived or that my parents had obviously failed when raising me. Advent calendars. Yes, I know what they are and, no, not having one does not mean that my parents have deprived me of happiness.

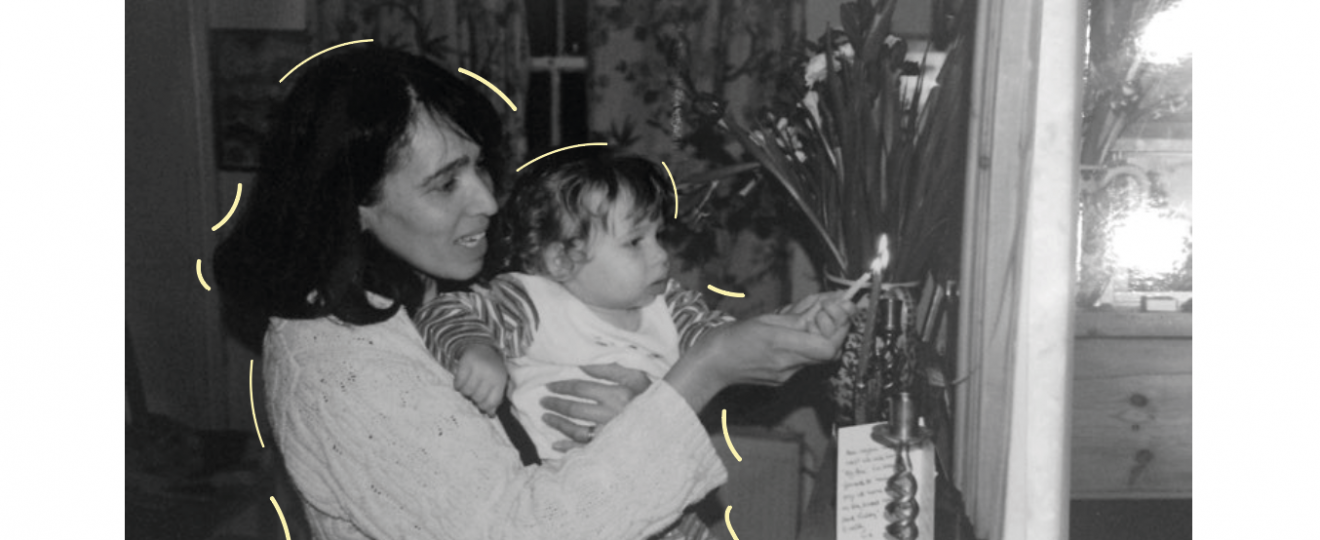

The feeling of being an outsider is also inherited. The feeling that something is not quite rights, the feeling that we are not completely at home is inscribed within us. As much as I see us all assimilating to one extent or another into the practices of British society at this point of the year. I also know that no matter how much any of us believe that we are fitting in, we will never truly understand and remain outsiders. You may laugh, confused at why children of dual heritage born in Britain could feel so alien at times, but I assure you it is nevertheless true. This feeling of not quite belonging anywhere, particularly at Christmas, is something that has been inescapably instilled in us by our mother since birth. My mother made a big point of raising us as outsiders. Brazilian when we did good and British when we didn’t. No English until school. Strict Jewish upbringing. No English food. The constant mantra of being different is good. A constant effort to prevent us from acting like what she said as ‘typical English children’. I grew up believing that this was done in order to plant in us the strong roots of our heritage, to avoid the ever so dreaded phenomenon of assimilation.

However, as I grow older and consequently able to take a step back, to critically question the truths that I have been conditioned to believe, I see that two possible further reasons present themselves. The first being that in drilling in us the notion that we were different and to be proud of it, my mother was preparing us for the probable eventuality that if treated as such by others, it would not come as a surprise or hurt. In creating a protective shield of pride in our culture, she has tried to ensure that any negativity would surely be deflected. The second being that in doing so my mother made myself and my siblings her allies. In making us feel like outsiders to this place as she did, she could have someone to turn to, someone to share her frustrations with, someone who could understand her. As the eldest, the brunt of the responsibility falls on me, the responsibility of being the pillar to hold up my mother when her feelings of alienation overcome her, a translation device through which innocuous comments by neighbors regarding whether our home wanted to be included in the street advent calendar, remained harmless and thoughtless, not thinly veiled attempts to stamp out our culture as was my mother’s immediate reaction.

When asked by others, stupefied looks etched across their faces, why Love Actually is not my favourite film this time of year, or why I am unfamiliar with the Christmas song currently playing on the Tesco’s sound system, it is not because I do not see these aspects of British culture as being worth my understanding. It is rather that these seemingly innocent products serve as warning bells, representing a time period wherein a constant weight rests upon my shoulders, mildly suffocating me, only to be released when the holiday season is over. A time period that reminds us yearly that no matter how entrenched you are in British society, no matter how much your friends love and accept you, you will never truly belong and will invariable take the position of the outsider. This is particularly difficult and challenging because as humans, we need to feel belonging, to feel included within a society, to feel accepted. History has shown us that those on the fringes, those who are not truly accepted are prone to discrimination, to hostility, and above all, apathy.

Photograph provided by Hannah De Almeida Newton