I was having lunch at my grandparents’ house when I was around 14. I remember it being a Sunday lunch, with chicken and lots of indulgent foods my granny cooked for us all. That might not be true. We were all there – my parents, my brother, my aunts, my cousin and of course Granny and Grandad. No one in my family drinks so when we have nice meals like that, we like to have some J2Os or Shloer. Something special, something nice. Granny has never been as health conscious as my parents (who would reserve such sweet treats only for truly special occasions) and so always had a good stock of fizzy and fruity beverages for her children and grandchildren to enjoy. For whatever reason, when we served the drinks, I decided I didn’t like the one on offer, so I brought a different drink out to have. I poured it out and maybe noticed a difference in the look? Maybe not, I can’t really be sure. But when I tasted it, I noticed the difference. It tasted disgusting. Fermented, rotten and vaguely fizzing. But I didn’t want to say that out loud to everyone, I didn’t want to complain to Granny that her drink tasted bad, so I quietly offered it to my dad to taste. He was equally as disgusted and asked his mum what it was. My 80-year old Granny had no idea what was wrong and might have apologised, might have dismissed it saying no it tasted fine? I can’t say with certainty. Then one of my aunties said that oh, sorry, that must be the celery juice from a few weeks ago. Because Granny replaced almost all the fizzy drinks in the house with homemade celery juice and carrot juice. Didn’t refrigerate them, left them out and forgot about them. So yes, that was probably mouldy celery juice you just had. Granny, who would cook the most buttery, salty, indulgent feasts and offer us sweets and biscuits and crisps every hour, had been keeping mouldy vegetable juice in her kitchen.

Then someone explained that a few weeks ago she had thought celery juice and carrot juice would stop Grandad from dying of cancer. And that, when it didn’t (or when he told her he wouldn’t drink that, or when her daughters told her to stop) she forgot about it completely. It didn’t matter anymore, if it couldn’t save his life. Which it couldn’t. Nothing she did could. And I had just drunk celery juice that tasted so helpless and desperate that I could barely eat afterwards.

My memories of my grandfather in his final months are few and far between. I remember watching The Artist one evening with my family and seeing that he was losing control of his body. He would apologise for disturbances, but we would all stay silent, not acknowledging his embarrassment or our pained sadness. That was around the time I went with my father to buy him adult nappies. I might have cried after both those occasions.

I remember being bed-bound with terrible period pain that Boxing Day, and while my family went sales-shopping, I stayed at home and watched Christmas TV in the living room. In the adjoining room, my grandfather lay, also bedbound, listening to old Queen songs. He was wearing a woolly hat on, even indoors. I don’t know if he had lost the little hair he had left, or if he was simply permanently cold. When ‘The Show Must Go On’ played, I felt an immense sadness at what I was watching. I don’t know what kind of sadness this was. I don’t know whether I was mourning my dying grandfather, or crying for the sad image of my grieving family that I kept being forced to see.

His children would take it in turns to walk him the length of the garden and back, every day. To stretch his muscles, so he could hear the birds and breathe real air and look at the life he used to lead. We would watch them from inside the house, and the growing image of death seemed to follow them even on the beautiful lawn among the apple trees.

Early in his diagnosis, when I still saw him as Grandad who looked like Wallace from Wallace and Gromit and never said a lot and was kinder than anyone should rightfully be, I spent a morning sitting with him on the sofa looking through a book of David Hockney paintings. An artist by nature and a teacher by profession (and actually the other way around as well), Grandad was wonderful at explaining to me the significance of each painting, both to the world as a whole and to himself personally. I think I loved art that bit more because of him. The year he passed away was the first year I decided I really loved art. I kept going for a few years, and that ended up being a massive part of my happiness and my identity in high school. I didn’t connect this at the time, Grandad and my new affinity for art and artists and artwork, but now it seems painfully obvious.

We lost Grandad around springtime. He was diagnosed in November, only a few months before. Seeing my father, his sisters and his mum, I saw the words ‘grief’, ‘loss’ and ‘devastation’. These were people I loved, and those were the words that were tied to them. My loss was less immediate, less cutting and certainly less consuming. I felt the loss of my father’s father, and constantly tried to teach myself what he must have been feeling. I felt my duty, as his daughter, was to experience his grief and not my own.

I am an adult now, and it has been seven years since this first encounter with grief. My only encounter with grief, I am blessed to say. Since Grandad passed away, I developed an affinity for art and creativity: every holiday we went on, I would drag my family to more art galleries than they were willing to visit; every school day with an art lesson would shine brighter than the others; I started drawing my family for their birthdays as a present and drawing the world as I saw it for my art teacher. It would slip into my mind, some dangerous and mournful and self-pitying thoughts. ‘If only’. If only he had lived to see this version of me. If only I could have asked him a hundred different questions that I am thinking of now, as I grow and live my life. If only I had been old enough and mature enough to understand him. To understand his silence and his strength and his selflessness.

I think if I had known him now, I would have wanted to speak to him about his life. Before his death I never managed to grow out of the selfish, insular mindset of children who see their own lives as central to everything – I was only interested in another person’s life insofar as it overlapped with my own world. My relationship with my maternal grandparents has become so beautiful and precious as I have grown up, and it has shown me what I might have had with Grandad. I missed out on a lot.

My father once told me that Grandad wanted to be a starving artist on the streets of Paris before he met Granny. Then he met the love of his life and chose responsibility and family. He became a teacher, a father and a husband. That was probably always his path, but I loved to imagine his alternative life down the road less travelled. I don’t believe I will become a starving artist on the streets of Paris (or anywhere), but I know I have that part of him in me. I live in a family of doctors, of scientists and engineers. My grandfather was my genetic, familial connection to the creative world. In the years after his death, I have seen more and more of him in me. I know where I come from – this present, adult, stabilised version of myself with an identity and an awareness of my hopes for the future.

I don’t remember visiting his house without him living there. I am sure I did, but those memories have been swept away by growing up. What remains are his last months, his last weeks. The scattered visits we made (the most often I have ever seen my family, what a horrible shame that is) and the seemingly abrupt changes in his condition between each visit. Staying in a Premier Inn instead of at the house because we didn’t want to overwhelm, we didn’t want to impose on a family that was barely holding itself together. I remember the atmosphere, the edge that was always in the air and would become most visible and unavoidably loud in the silences.

That was the house his children had grown up in. The only house I had ever known my father’s family in, that I would visit every Christmas holiday and most summers. My memories of that house have been flooded with grief, painted an unrecognisable colour. I can’t think back on any part of that house, the family that lived within it, without focusing on some form of loss experienced by those people, my family.

Granny has dementia now, and lives in a home near my parents in the north. Their home was sold away years ago. The children had the task of emptying it – removing five entire lives from that house. No one lives in their hometown anymore. I think sometimes they all go to visit Grandad’s grave, but I haven’t been in years and I haven’t seen his grave since the funeral. That whole city is detached from me now and will maybe only be a memory. I know the river, the cafes, the walk to the park, that funny hardware store with the smutty name and the chip shop next door to it. I know the Italian shop and the shopping centre and the bad sculpture in the town centre. There were always some street artists, living statues or magicians hanging around that often delighted me. There was the auction house (the only one I’ve ever been in) that I never really understood. There was the garden with the apple tree my father planted as a kid and every time I visited, I would ask him which one it was. The whole house was old, made of old people and old people stuff – the stuff that you could only accumulate over many years, from a massive and diverse pool of friends and relatives, that you keep because you are at an age when memories make up most of your life. You have lived your life, and here is the proof. It was cluttered and old-fashioned and not very stylish, but it was the most lived in, living, loved house. It couldn’t survive after Grandad passed away.

There was a double rainbow on the day of your funeral. I know that every time he sees a double rainbow, your son sees you watching over, saying hi. When I was younger, an awful teenager with a warped moral compass, I used to think about you watching over when I was doing something bad. I used you to attempt to shame myself into being sensible, wise, mature. That wasn’t you, I know. That was just my poor form of self-control and morality. I don’t know what I think now. I think if I had known you better, if I had been older or just been better at listening and remembering, I would feel you more now. It is a great loss, I believe, that my memories have been eroded by time and that they were all from a child’s perspective anyway, unreliable and self-centred. I’m sorry that I never really knew you, beyond the way a girl sees her grandfather who is quiet and kind and lives far away. It isn’t fair that I will never know you more than I did when I was 14. I am sorry that’s gone. I felt so cheated when I realised that I wouldn’t receive any of your illustrated cards after my 14th birthday. My brother got three more than me. I didn’t think that was fair. It wasn’t long after you died before I drew my first birthday card for someone. I never connected those two things until now. I’m sorry I didn’t see the gifts you gave me, only the things that had been taken away.

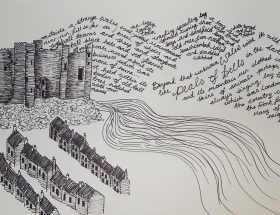

Art by Sophie Dickson