We all live through stories. Continuously so, regardless of whether we are choosing to dream, to read, perform a play or watch one, the central story of our life is one unfurling in our own minds, fixing on fleeting moments and elements, compressing the expanse of the world into a narrative we can understand.

This past year has felt like falling into water and being caught by a current, suspended below the surface of life, uncertain and afraid.

Boccaccio wrote the Decameron from 1348-52, the time of the Black Death. Florence was in disarray. As is still apparent, cities suffer badly in pandemics. Shops back then were empty, like today, although without the convenience of arranging click and collect or a next-day online delivery service such as Amazon (that company we all seem to hate yet never actually stop using). More shockingly (for the 14th century), churches were also closed. Life had shut down while they waited for the plague to pass over, praying it would leave them and their loved ones untouched. The death toll was considerable. An estimated 60% of Florence and the surrounding countryside died.

The Decameron centres on seven aristocratic ladies: Pampinea, Filomena, Meifile, Fiammetta, Elissa, Lauretta and Emilia. They are friends of varying ages, who decide to leave the city for a country estate and remain there for a while until the worst has passed. Not wholly dissimilar to those who left cities in earlier lockdowns here to scramble off to country dwellings with larger gardens to roam and ‘reconnect to nature’. Boccaccio justifies this by clarifying that these friends have lost all those they had stayed for, thus whilst being very unfortunate, their virtue and morality are secured. The ladies are accompanied by three gentlemen; Filostrato, Dioneo, Panfilo, to complete the party of ten. They pass their days in self-improvement, and spiritual contemplation (the fashion before banana bread, jogging and sourdough mothers). They also tell each other tales to pass the time.

They spend ten days, with a story told by each, and by the end the stories number a hundred in entirety. The tales are often of love, they are often scandalous and spiritual, combining elegance and shit (rather literally). There is often a contradictory clashing of morals, a muddle of High and Low, but all are stories of their present, interwoven with contemporaneous details such as well-known figures or places. They present a life beyond the plague and beyond the walls of the estate;I the stories are a way not only for the characters to connect with each other, but also with their context and the normality that has been lost as an effect of plague. It is a tale within a tale, framed by conventions of Courtly Love and notions of pastoral idylls, but it was wholly a thing of the present. Boccaccio even wrote it in Italian when Latin would have been the expected form. A search for a wider audience, perhaps, even whilst still limited to the literate, it at least expanded beyond the Latinate.

Boccaccio’s Decameron inspired other authors such as Chaucer, and many paintings. It is exemplar of how we communicate through Art, be it stories or images, and each attempt of communication is one of connection in a world where isolation feels rife and existence increasingly insular. It is a mode of thinking beyond ourselves and reaching out to others, even if they existed in the past.

The friends in the tale choose to return to Florence at the close of the work. The stories, far from being an escape or avoidance of reality, were a source of renewal and hope. Their restorative quality provides not only the chance to dream, but the strength to go on. They do not emerge from their diversions to discover the disappearance of pestilence, but that does not matter.

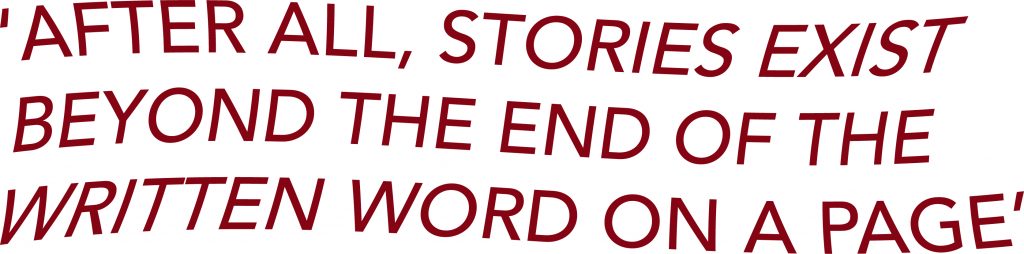

After all, stories exist beyond the end of the written word on a page. They dwell in our minds and live on in our dreams. The promise of a future is what Boccaccio chooses to leave us with, the sense that these characters, like us, will go on.

Art by Desiree Finlayson