When, in April of 1986 near the Ukrainian city of Pripyat, the No. 4 nuclear reactor of the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant shutdown, life and people’s sense of security within it, crumbled to bits. The nuclear disaster, rated as one of the two most dangerous international nuclear events (rivalled only by the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan), created a significant rupture in the usual proceedings of existence and called into question concepts of everyday life that had previously been taken for granted. It was the shattering of everything that was normally ‘blindly’ trusted. Belief in and reliance upon ‘specialists’ (medical professionals, scientists, government figureheads, international organizations) were squashed beneath the realization that there are some things no one can prepare us for (after all, how specialized is a specialist if they can’t predict something like this could happen?). Senses of stability were thrown into an abyss of confusion and chaos, and from it was birthed the horrifying understanding that we, as people, may never truly be ‘safe’. An understanding that reminds us: anything could happen.

This same deconstructing and reconstructing (and general rupturing of people’s sense of protection or safety) has occurred after many a tragic event: Earthquakes, wars, tsunamis, death, break-ins, break-ups, chemical explosions, and a myriad of other grim but very real occurrences that all exist in our lives and the lives of many others.

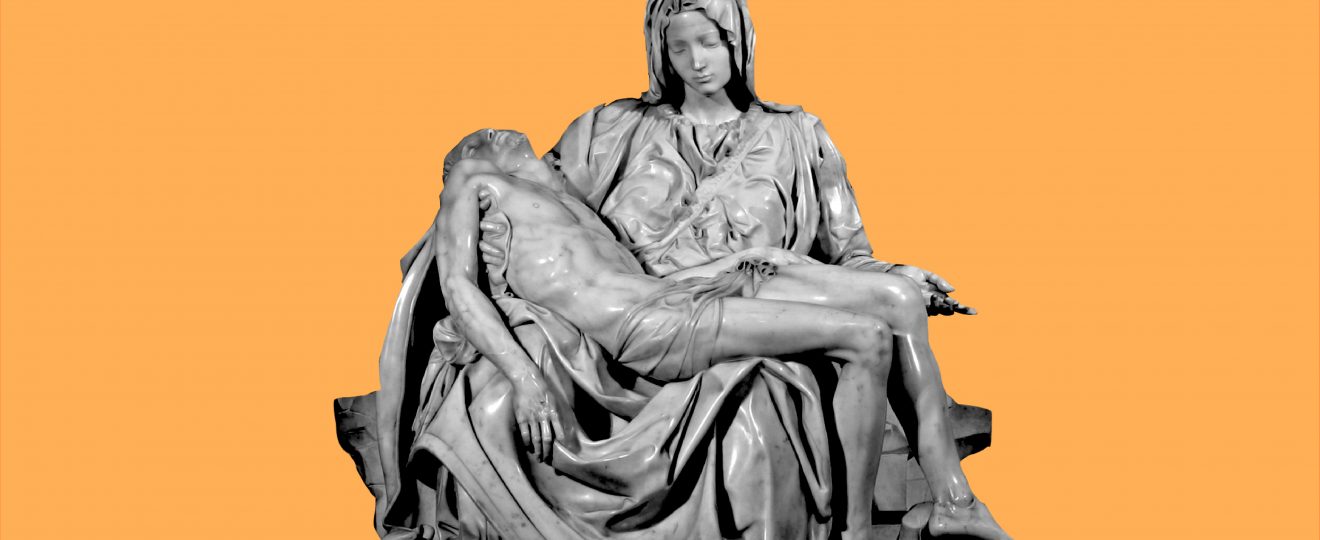

As someone who has just endured a quite unfortunate and rather significant life event, I have truly come to see the extent to which tragedy (and consequently grief) is at the forefront of culture. Art is inundated with it, movies profit from it, dinner table discussions centre around it, heartbreak songs are blasted about it. And we seem to love to indulge in it.

Call it what you will! Perhaps it’s the same as our shared and grotesque curiosity surrounding suffering as a whole. A diverging strain of the ever-present ‘it’s-so-bad-but-I-can’t-look-away’ mentality; the same mentality that fuels our true crime television show marathons, our listening to murder podcasts on the bus at 9am, our horror film movie nights.

Maybe, it’s a protection mechanism. The more we discuss tragedy, the more we may neutralize it. The more prepared I myself can be! The less the tragedy can surprise me or throw my life off course, the more control I retain over an intrinsically chaotic event.

But what is for certain is that, through the millions of recreations of tragedy we have fashioned into artistic or discursive existence, we have created some sort of mentally and emotionally digestible version of it. We have written some handbook on what tragedy is and how to deal with it, as though grief and the act of navigating yourself out of it were a four-step process congruent to building Ikea furniture.

For one, we have made tragedy out to be inevitable and expected.

(“Life is a drama full of tragedy and comedy.” ― Jeannette Walls, The Glass Castle)

It is to be used so as to motivate one’s individual strength: If you survive it, you supposedly unlock some secret superhuman resilience you were unaware you contained.

(“Until a tragedy touches you, you will never be able to fully understand what life really is!” ― Mehmet Murat ildan )

It won’t be oh-so-tragic, eventually.

(“Humor is tragedy plus time.” ― Mark Twain)

And the healing that follows tragedy is extremely linear. Things go from worst, to bad, to unpleasant, to understandable, to okay, to normal, to maybe even good.

(“After a tragedy, a farce. Philosophy enters into her power, and the earth returns under one’s feet.” ― Lev Shestov, All Things are Possible)

In my eyes, however, these supposedly recurrent properties of tragedy are mere attempts for us to restore some order to even the most chaotic of situations. Our attempt to metaphysically colour-code and alphabetize suffering- bureaucratic comfort served to us on artistic platters. Books that promise a road of recovery, or movies that cut to ‘5 years later’, when everything is resolved and you’ve cut your hair and that past pit of grief is something you think of with some soft bittersweet smile because you know what? You grew from it!

But now (more than ever), I have begun to understand that the ‘tragedy’ that had been explained and averaged-out to me in the many aforementioned avenues of consumption, clashes harshly with the reality of it all.

I’ve realized that while, yes, life probably is solely a series of good and bad events turning over each other like pebbles in some archaic stream (as so many quotes say), what surrounds it all cannot ever be universalised or perfectly planned out. It is always, in its nature, strange and alien, and perhaps unlike anything you may have expected it would be like.

In the movies, a horrific event happens in slow motion with the swell of some emotive orchestral cacophony. A gaping mouth screaming a “NooooO!”, a hand clutching a forehead, a crumpling to the floor. And what follows? A montage of someone in sweatpants on a couch, blowing tears and snot into tissues, watching movies on rotation.

Personally, I spent a solid hour after the tragic event that occurred for my family and I sitting upright and fully clothed on my bed like a capital letter L, hands folded in my lap, Claude Debussy playing on my phone (lyrics were too much to hear and silence was WAY too much to hear), thinking to myself:

‘How the fuck am I supposed to behave when something horrific happened only four hours ago? How can someone be simultaneously so freshly free from and completely intertwined with tragedy? Where is my montage to cut to five years later? Where is my goddamn bittersweet soft smile!?’

And nothing has been linear, either. No ‘day by day, it gets easier!’.

Each day is a wonderfully shocking surprise. A new attitude. A new emotion. A new perspective on the world, on the event, on myself.

And I suppose what it has all made me learn is that, while we, as a society, speak so frequently of tragedy, we are absolute fools if we believe that that could ever mean we have any sort of grasp upon the concept. It’s comedic that we could think that we somehow made suffering formulaic enough that it (maybe!) can’t hurt us as deeply.

I don’t say this all to be cynical. In fact, I’m writing this with an excitement and optimism spurred by (what I think) is a good and different take to it all.

The best way to prepare for tragedy, is to realize that there may be no way to prepare at all.

Anthropologists who work in the field of Postsocialism have drawn ties between the existential rupturing caused by Chernobyl, to a term coined by Veena Das in her 1996 book on contemporary (it was contemporary then) India. In the book, Das discusses how certain powerful events (she calls ‘critical events’) cause a redefining of the world and restructuring of classical categories within society. These are events for which no one can prepare, and ones that splinter life and the way people order it from there on out, just as Chernobyl destabilised people’s trust in specialisation, in their government, or in their scientists.

While critical events and their implications are discussed, the term seems to be reserved for wide-scale events that are being analyzed anthropologically. But the way I see it, there may be no better way for us to understand the way we feel or what to do after terrible things happen, then by understanding that we are grappling with an upheaval of our internal order. An upheaval that cannot be rectified by a recreation of what we have ‘seen’ others do before. An upheaval, so innately personal (on such a small and introspective scale) that you understand that you can’t and won’t prepare for it, and that for as much solace as you may find within quotes and songs and books and familiar portrayals of suffering and grief, you will find just as much isolation or alienation that distances you from earth, as though these portrayals or experiences are just vapid contortions of pain bent into something so easy and so ordered you could scream at the seeming inaccuracy.

If tragedy is in and of itself, extremely strange- nonsensical, inexplicable, unexpected, and nothing if not un-special- why should we ever expect otherwise? Indeed, it is the allowance of fluidity, the acceptance of chaos, and the welcoming of a deconstruction and subsequent reconstruction of our lives, that could prepare us even in the slightest for suffering or tragedy or grief. Our earth can hardly be shattered if we begin to see it as rubber: malleable and changing with us, as our realities adjust to new experiences, and our mental ordering of things follows.

—-

(For what it’s worth, I HAVE found solace, in so many quotes and songs and books and movies. Countless, as a matter of fact. Some (as I definitely made clear) have made me irate, yes. But so much of art and so many portrayals of grief have indeed provided me with comfort. One quote in particular that I enjoy currently is:

“The tragic view is the most cheerful. One sheds a lot of illusions and learns to laugh a lot.” – Marty Rubin.

Thanks Marty. My critical event has given way to this too.)

Wow Jade, that is one impressive article. Proud of you.

Brilliant, articulate, and filled with depth and breadth.