Ever felt nervous before a job interview, not because you think you are not skilled enough, but because you may not have the right clothes or your accent is ‘too Northern’? Ever gone to school and hoped your classmates wouldn’t mention that you get free school dinners, and don’t bring your own homemade Piri-piri wraps and kombucha? Ever spent nights awake, fingers and toes and arms and legs crossed that you get that scholarship to go to university?

Dead Ink books has got you.

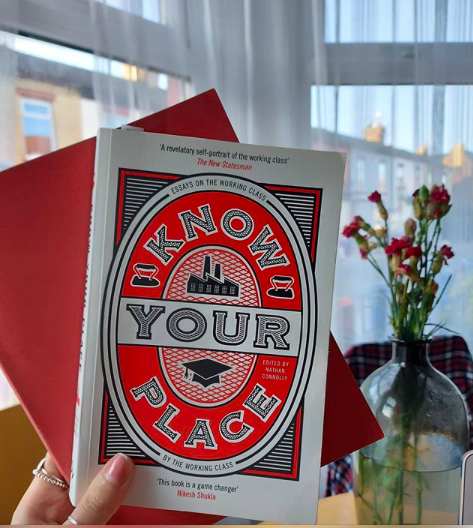

From Liverpool-based Dead Ink Books, Know your Place is a collection of essays from 24 writers that consider themselves working class, examining the issues surrounding this through the pens of their own personal experiences.

I didn’t know how to feel for at least a couple of days after reading this collection, what with the complexity of defining a class, its people, their habits and customs. I’d say it was pretty impossible. The collection leans towards the confusing considering how the low socio-economic rhetoric in discussing the working class grapples with the notion that the majority of Know your Place’s writers have (self-professedly) ‘escaped’ through education and ‘hard work.’

Some describe the textbook characteristics of having working class roots (which I identified with deeply and thus enjoyed); of being the first university-goer in your family; of entering the working world (albeit a casual, cash-in-hand basis) during early adolescence; of being acutely aware of the differences between yours and your school friends’ packed lunches (how could I keep pretending I knew what Nutella was??!)

But it was Kath McKay’s essay, ‘Reclaiming the Vulgar’ that made me want to re-enact a The Breakfast Club style fist pump in its joy, its celebration of the working class. Small, anecdotal snippets, affirmations you could say, often made me physically nod my head in agreeance…

‘…sitting on the front steps is ‘common’… but sitting in a back garden is fine; eating chips on the street outside Leeds Market – common?; on Aldeburgh beach with a chilled bottle of wine – acceptable?; ‘street’ food – edgy?’

Displaying experiences of many writers who have arguably traversed the working-class boundary – an opportunity not open to all despite the circumstances- this collection was destined to be one of hope. On the one hand, this aspect can be seen to skew the perspective of the collection as a whole, however I would argue that it may represent a text that is needed.

For working class readers (from the UK in terms of specifics but not exclusively), this is a conspiratorial nod and pat on the back, a reclamation of the fabric of our upbringing and personalities. For others, this collection is a nuanced, sensitive and fresh examination of the working class experience, which if nothing else, should breed a deeper and more expressive understanding.