Location—where we are, where we are going, where we have been—has never been more important to us than in this year. This year of stay-at-home, of work-from-home, of study-from-home, of stare-at-the-same-four-walls-from-home, of lose-your-mind-from-home. Collectively, we have all stayed in the same location more so than for the vast majority of our lives. Never, since the invention and mass commercialisation of air travel, or perhaps even of steam-travel, have we spent this much time in the same places, in the same buildings. For this year, this stultified, unchanging year, we have perhaps timewarped into the Regency-era lives of Jane Austen, or even the Tudors. When I talk to friends, I find myself writing and how, may I inquire, are your families? Are they healthy? Are they primed for winter’s chill? I send my prayers for their god-given protection. I also find myself staring out of my bedroom window at the same view I have stared at for the majority of the year (aside from the short intervention of the September-November university excursion), wondering the philosophical questions of life, reminiscing and longing for the Spring season. Do you remember the lights? The yellow glow on people’s faces? Kissing, hugging, sharing bodily proximity without care, swapping pathogens like phone numbers? I look morosely at the driveway, remembering when cars (or carriages, if we’re in keeping with the metaphor) crinkled down the stones. I look at the rooms I have haunted like Mr Rochester’s poor wife since March and I imagine them full, of friends and faces, and bodies. I am introverted, though the truth of the introverted/extroverted dyad is up for debate, and if even I am looking at my home as a shell where bodies and memories once celebrated the joys of social interaction—well. Let’s just say, things must be bad. Poor extroverts.

Perhaps a good thing about being so static is that our locations, where we are, have begun to matter more to us. My Mum has surely not been the only one to embark on spring, autumn and winter cleanings with a fury and fervour unmatched by Achilles swinging the dead body of Hector around as he rallied his chariot about the walls of Troy, but instead of the bloody corpse of the local strong-man it has been pairs of my father’s shoes that he has left by the front door held furiously aloft. There is a sketch in the iconic bastion of culture and education that is Bob’s Burgers (my references are always of the utmost academic calibre). It is a snippet that could be easily missed, in Season 2, Episode 6, where Teddy the Handyman tells a story about noticing that two of his towels are slightly different shades. ‘I was thinking, were they the same colour when I bought them, or have I washed one more than the other over the years. What do I do now? Do I wash the other one intensely to get it to match? Do I return them? Do I pretend I never noticed? Can I still use them as guest towels? When am I going to have guests? I don’t know!’ This snippet, this story, sums up entirely my feeling towards my house, towards the little nest my family have buried ourselves away in. My eyes have focused on nooks that previously they have skated past for so much of my life, examined the same door frames I have walked past thousands of times, looked at the garden, at the droop of the flowers, with the eyes of someone who now has the time to see, properly. This beauty, this falling back in love with the familiar and discovering the new, is the driving force behind Ananya Jain’s brilliant cross-media piece examining her familiar, her homes, and finding the magic of the new within them.

Beyond love, however, in our examinations of the everyday, we find spots that need changing, that need upkeep. We have the time to think, the time to turn over every stone, to criticise the paint colour and fall in love with the fireplace again. Much of this issue deals with this re-examining, with the time we now possess to stop and think about the familiar places we have taken for granted for so long. The world is an extension of our houses, (well, we live in it, don’t we?), albeit a huge, ungainly place with far too many corridors and windows that constantly need reglazing and a garden that is always falling back into disrepair. When we have the time, why not make some much-needed reappraisals, and some reconstructions, and repairs. This pandemic has proven that we cannot keep living with the leaky tap, and the window that always lets the draughts in. Jade has excelled herself, as she always does, with her brilliant discussion on the discrepancies and injustices in our medical history and treatment depending on time, and the bodies upon which these grievous injuries have been enacted; her personal, heart-wrenchingly candid reflection on personal illness and the fatality it could have been strikes a particularly pertinent chord in these times of world-wide sickness. If, as Jade so eloquently discusses, our medical world, our medical knowledge has been by and large founded on the bodies of white men, how much has slipped through the cracks? As she discusses with regards to asthma and childbirth, this bias is disproportionately affecting women and people of colour; a similar trend noticed with regards to COVID fatalities. Just like a home with a faulty gas-line, we cannot keep living in a world that is not designed for the safety of those inside.

These ideas are present, albeit in a different form, in Honor McGrigor’s interesting and illuminating repose on ideas of location and addiction, in which Honor ponders both the physical and psychological affect that different locations will have on real, pertinent issues, and on the states of our being. Focused in on the lens of the opioid addiction currently ravaging America with the same tenacity and a much larger longevity and morbidity than COVID, Honor discusses the way that our senses, the ideas we impose on our home, can tremendously affect our behaviour and our mental health, with a sharp wit and a clear, engaging voice, proving that where we lay our sweet heads is massively important, and worth studying. Nadia Lee’s devastating, beautiful, bittersweet examination of how a home can change and be changed by the actions and events that take place within it also lends a nuance to this examination of the places in which we live. Discussing grief with a candour, a brilliance in description, and a tragic vision that I have nowhere near enough elegance to accurately condense, Nadia’s dissection of a home made unrecognisable by the grief within it will resonate with many, and as I have explained above, any attempt to abridge it will do a disservice to the strength of this work, and I truly encourage you to read it yourself. Lastly, an examination of the places you live in, and love, but perhaps do not understand, is the main crux in my article on Dylan Thomas and his unique relationship to Wales and being Welsh. (What is the editor if not an egotist, reader?)

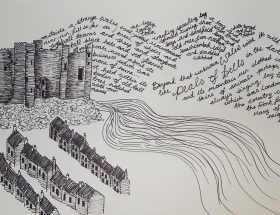

But beyond our homes, beyond our static familiar, there are the locations that are equally important to us this year in their absence, in their missing; as the house becomes a shell, a receptacle for old ghosts, when there are no bodies to fill it, our bones have ached for the places we could not go this year. I have found myself spending an absurd amount of time thinking about holidays, the places I visited as a child, or as a teenager, and knitting myself a fairytale tapestry of their beauty as a means to comfort. My personal favourite, as a child, was a little snow-covered town called Stowe, in the purpling mountains and endless, wet-green trees of Vermont. There was a house there, on the mainstreet, with dark blue doors and a crescent shaped window, that I dreamed about, that I would look up to with glossy eyes every time we passed it. I can smell that town, sharp pine needles and warm chicken noodle soups and the clean, damp, scentless scent of snow. I can feel it in my hands. I long for it, I ache for it, I spend my nights dreaming I am walking on the soaked, slushed pavements up to the slopes in my heavy ankle-weight boots, more so than I ever have. This longing, this dream of the different, is present in the beauteous poems of both Lizzie Milne and Jade Mkparu, whose loving craftsmanship has created glassy, brilliant worlds so rich and vivid you can step in, and for a minute, be somewhere else. Lizzie’s evocative descriptions of her grandmother’s place in Skye is so vibrant and gilted that you can smell the mist from the mountains, you can taste her grandmother’s stew; for a world so starved of a holiday, when you read Lizzie, you can at last be satisfied. Jade’s lines unravel a place once golden in their heydays ruined by decay (a feeling I’m sure we all relate to) and in her stark, tactile words one feels as if they are standing with her, amongst the silent rubble, seeing the world through her jewelled eyes.

Louise Evans and Keyona Fazli have taken a different approach but one no less fantastical in exploring different locations, and discussing how we find new places within the ephemeral through the two mediums that have witnessed a pertinent boom in the world of COVID; books and music. Louise’s dissection of the rich and love-steeped worlds of Bolu Babalola’s fairytales both evokes the far-flung and bright worlds that the author creates, and exposes the universal, modern themes that underpin her gem-dotted escapist pieces. The clarity and emotion that Loise infuses into her examination of Babalola’s work is infectious, and will have you, like me, ordering a copy. Keyona’s warm exploration of what songs mean, and the lucidity of the places they can create through both lyrical genius and the composition of the songs is nuanced and personable, and will resonate with all of you who are like me (God, I am sorry if this does apply to you, because I am a strange, strange human being) and have spent an inordinate amount of time closing your eyes and listening to your favourite artists, willing yourselves to be in the worlds of their songs.

Perhaps the piece most illustrative of the two attitudes towards location that have dominated this, most strangest of years, is Anna Kerr’s exploration of what exactly home is. We have been preoccupied with the places we live, and we have been preoccupied with the places we haven’t. We have fussed and obsessed and examined our own bedrooms, our gardens, our kitchens; we have fantasised and ached and dreamed about the bedrooms, gardens, kitchens of other places. Perhaps, then, neither of these places, here or there, are home. Perhaps they both are. This nuance, this duality, is captured with Anna’s thoughtful, conversational, honest piece. She sums up the complexity of identity, of home, of people and places and things, with an ease and an engagement that many, many brilliant authors of yore have spent their lives trying to elucidate. Home, to Anna, is nowhere and everywhere, in people and in places. I will say no more than that. You must read it to hear more. (I hear mystery is how you hook them in, see, reader.)

As I am writing this, I am in my bedroom, perched on my bed. My dog is curled up at the bottom, near my feet (if you do read my article, this is not the liver-spotted rotund spaniel, but rather the little, naughty black spaniel who has the quickness of shadow and the cheekiness of a young Shirley Temple. My lamp is on, and half the world is pearly with its warm glow. My boyfriend is next to me, watching some bizarre video we both enjoy. I can hear the evening crows of birds from next door, and from the half-slice of that old, familiar window I can see green. I can see crooked trees, and blue skies, and translucent, sundown clouds that drape themselves like party-paper over the winding branches. This is my location, reader. It has been for most of the year. This issue of BRIZO has made me examine it, turn it over in my hand. It has made me measure its cracks, search for the emotions under its plaster. It has made me appreciate its sights, linger over its colours and smells. It has mapped out a whole new world in my own familiar. With the beautiful work of its authors, the splendid, supreme art of our brilliant creators, Kate, Quinn, Mafer, Desiree, Sophie and Jennifer, whose inhuman talent with brush, pen and colour I could never hope to sum up in mere words, this issue has uncracked my place, and brought out its beauty again.

I hope it does the same for you.