Content Warning: This article discusses true crime and details pertaining to violent events/acts.

I have brown curly hair that is usually styled in a centre (ish) part. I am white. I am a young woman (22 years young, to be exact with you, and feeling every bit the age, if not more so).

Do you know who I share those features with, whose looks my own mirror, whose appearance I mimic?

Ted Bundy’s victims.

Bet you’ve missed this, right, reader? Welcome to Goretown, population you. (and me!)

People say the first proper incidence of True Crime – works of literature, film, or music that centre around real events of murder, rape, theft and violence – is Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood. (If you’re wondering, I’ve capitalised True Crime because this rather fetching lady is a striking and prominent figure in our discussion and deserves her full due. If you’d like some help visualising her, to me, she looks like the Black Dahlia – all coiffured black curls, jewelled, lung-red lips, a suave, well-tailored suit, and with a variety of life-ending injuries that cover her in rich blood. Imagine a particularly goth album cover, or the vengeful ghost lady in a wildly exploitative horror film). A fascinating story of a small, random, Kansas familicide committed by two criminals looking for money, In Cold Blood is also wildly exaggerated and often untrue. Capote, obviously, never met the Clutter family – they were buried long before he rolled into Holcomb, Kansas with his pal Harper Lee (don’t you love it when there’s a crossover episode between authors?).

Despite his lack of acquaintance, Capote felt pretty confident in casting aspersions on the people who were so senselessly, stupidly, and unjustly murdered. Herb Clutter, the family patriarch, was a prosperous farmer who was known for his fair treatment of workers, his morals, and his good wages. In Capote’s telling, he is a bit of a grinch, a bit of a tightwad, a man stuck to the earth who doesn’t understand his wandering Ophelia of a wife, Bonnie. Bonnie, in the book, is a woman strung with an emotional depth and intelligence that exceeds her small-town America life, unsatisfied and depressed by the crushing ennui of the golden fields and heavy peach trees of her healthy, rich farm. (Capote makes no bones about his slight disdain and condescension for Holcomb. The town appears simultaneously as a black, shadowy place full of affairs and grudges behind the veneer of gentility, and as a backwater idyll removed from the reality of life, a valley of apple pies on window ledges and unlocked doors, with the implication it’s a wonder it took so long for a whole family to get ripped apart in the middle of the night heavy and glaring). Nancy Clutter, the couple’s sixteen-year-old daughter, is almost spoken about with a sheen of oily resentment: her gentle life of 4-H meetings and looking after neighbourhood kids, of healthy, modest appreciation for exercise and sweet handholding with her boyfriend – that lovely, placid life is a point of derision for Capote, who at once feels sorry for her and sneers at her desire to chart a rather expected and well-trodden course of wifedom and bake sales and bouncing, red-cheeked babies. He is bored with Nancy, whose only real intrigue comes in the debate between the criminals whether or not to rape her before they kill her. Other than that, he isn’t interested. Their son, fifteen-year-old Kenyon, gets even less of a mention, existing merely to throw a football about, push up his glasses and wear a jersey.

Capote’s real interest lies in the two women who are murdered. He likes Bonnie because her clinical depression allows him a route in to criticise middle-America life and heteronormative marriage (which, hey, I’m the first to hop on the bandwagon for that, believe me – but is it a bit icky to use a dead woman to make these points? I think so. Take your shots where you can, Capote, but not over a bullet-riven corpse). Nancy catches his eye because her body becomes a battleground for lascivious debates over sexual assault, nubility, and paedophilia. Apart from his leading ladies and their particular quirks, the victims serve only as the background to his greater loves within this twisted and bitter tale of blood and rope and heavy cherry trees – Richard Hickock and Perry Smith.

Hickock and Smith, coincidentally, are also the men that drove up to the house of a family they didn’t know, and on the off chance that there could potentially be money in the safe, tied up a man, his wife, their son and their daughter, debated over the writhing body of that daughter whether it was okay to violate her prone form, and then shot them all in the head.

They also were alive when Capote wrote the novel, in 1966. They were able to talk to him, give their side of the story, unravel the abuse and poverty and disgust and need that battered them into the callous (or not-so-callous, as Capote spends so much time lovingly illustrating) killers that they were. It gives them a stand ostensibly for explanation, with the excuse of helping people understand murderers, and thus preventing new ones from springing up in the future.

Do you think, reader, that it actually does work this way? Do you think that they are honest about themselves and their crimes, that they say, yeah, that’s on me, actually – I was a real shit, an inhuman monster, and though I have been through difficulty and abuse myself that doesn’t give me the right to go and murder a family of four? Do you think that they hold their hands up and say, it’s true, just because I didn’t like my mum it’s not right I took pleasure in spraying that woman’s brains out all over her nice stucco walls? Do you think it was really written in the pursuit of the prevention of more killings, to take away the glory and mystification of these men, and show any potential serial murderers stalking the aisle of Waterstones that their heroes were sad, weak, desperate men who lashed out with utter depraved brutality against good, kind people?

Or do you think they speak over the bodies of those they put in the ground? Do you think that they become men of circumstance, moulded into tragic Romantic heroes by dark pasts? (Romantic in both capital R and regular r – some people, including maybe Capote, found Smith and Hickock and all the other killers that have stalked our streets since then, Bundy, Dahmer, the Columbine boys, Ramirez, attractive. I know, I know, weird – we’ll get onto this later). Do you think they become wild, feral men who carried out the ultimate crime and in doing so became blood-soaked gods? How many times do you think they blamed their mums?

If you thought it was more likely the latter, that the killers take the mic with glee and leave the victims behind in the dust (I know you did reader, so if you say otherwise you’re just being contrary), then, ding ding ding, you were right! Although arguably Hickock comes across a bit of a weak sleazeball, Smith is a tragic hero of poetic proportions.

And in this, though I absolutely do not think that In Cold Blood is anywhere near the first work of true crime (just look at the Ripper murders, which, wow, no joke, the newspapers don’t shy away from describing the amount of organs each victim was missing and the deep, gooey slashes in their stomachs and faces, often with a good dose of ghoulish glee), I can agree that it is a perfect example of why the genre sparks controversy everywhere it brushes its cloak. The victims have no voice and are likely forgotten, violated all over again on the page, often by male authors who take a particular gruesome pleasure in the obsessive, detailed retelling of rape and sexual violation. The killers are the celebrities of whatever book/podcast/film is rehashing their sprees, their particular murders combed over like top-ten hits – the more wildly gruesome the better, the more dissected, played over and over again till the album sticks and scratches. Imagine, Ed Kemper is Britney Spears: his murder of Aiko Koo is Cinderella, a fair few plays, but the murder of his mother is like Oops I Did it Again! – bigger, louder, more memorable, sung over and over by a million different voices. Not only does this do a massive disservice to the victims – suggesting their deaths are no more than chapters in the larger story of their killer – but it also feeds into the narcissism and self-obsession that many of these men (let’s be real, it’s like 90% men) treasure just as deeply as their bloodlust.

As a genre, True Crime can be exploitative, revelling in the darkest, most brutal, bloody, and insane moments of human history with no thought or respect for the living families or the victims themselves victims (many of whom are, in the biggest, most-discussed, true crime cases like JonBenet Ramsey or the Green River killings, women and girls who have been gruesomely sexually assaulted). It can be wildly exaggerated and untrue, dipping into tropes of gothic horror to describe the guts and gore of crime scenes the authors have never seen, imagining emotionally resonant moments of détente and resolution to bring the story/fact to a close (in In Cold Blood, Capote invents a scene where Detective Dewey talks to the family’s graves, an event Dewey confirms never happened). It can glorify awful, awful people and erase those they victimised, it can inspire copycats to try and achieve the same notoriety and fame as the heroes that slayed and ripped and violated and in turn received unholy amounts of attention. It can draw in vulnerable young women and make them romanticise abusive and violent men.

It can be awful, repulsive, hurtful.

Why, then, do I – I and so many other women – love it?

____________________________

Do you know, I had a plan for the alternating parts of this article. If you’ve read my other pieces (self-promo never hurt nobody) you’ll know that between the meat of my arguments I like to spend a bit of time talking about stuff that is tangentially and emotionally related – specific Jane Does in that one, the facts of the Borden case in the other (there’s a theme here, isn’t there?). I had a plan for this one, too. I thought it was all set out, how I was going to really make this topic resonate.

I thought – I know what I’ll do. It really gets right on my pip, see, if you’ll forgive the gratuitous understatement for what is a huge and terrible problem, that two years ago, Joe Berlinger released Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, a film about Ted Bundy with the absolutely repulsive choice of teen heartthrob Zac Efron as the man himself. There are countless articles written by authors far more talented than I on why this was such a reprehensible choice – not only does it play into the blame-the-victim mythos that Bundy was so strikingly attractive (he wasn’t) that he seduced his victims into his VW Beetle of death by gyrating his hips and giving them the eye (he, in actual fact, pretended to have a broken arm, and deliberately targeted girls he thought would be kind enough to help him load things into a car) and as a result they deserved it – but also by casting a man who was many girls’ first crush (including me. He was just so earnest in High School Musical, wasn’t he?) it perpetuates the socialisation of young women to believe that violence and degradation is an appealing prospect indeed. One cursory glance at twitter in the weeks after that film was produced sees a sweeping array of tweets from teenage girls debating whether Ted or Joe from You was more attractive, or saying, well, it really is quite romantic, isn’t it, to have someone love you so much that they want to tear you apart?

Berlinger’s excuse for this was that women at the time of Ted Bundy’s arrest thought he was attractive (and he used the case of the particularly weird one who started styling her hair in a centre part and mouthed ‘I love you’ to Bundy in court, causing him to ask for her to be removed because she was ‘making him uncomfortable’ – which, bit of a weird achievement, isn’t it, creeping TED BUNDY out) so he was only staying true to form. Respectable journalists and filmmakers would have identified that the problem of teaching young women to romanticise and fetishise men like Bundy did not need to be brought into the modern era, and that perhaps igniting ‘Bundy fever’ in 2019 was not the most moral choice. I digress.

The problem that I think is first and foremost shocking is that Bundy was an out and out narcissist. He thrived off the idea that people thought he was an inhuman monster, psychologically rent from the normal population, somehow bigger, badder, unconquerable and unconceivable. He thought there was glory in being horrifying, the ghoul at the end of the bed that spread fright wherever his name was whispered. You can see it in his damn smirk from the courtroom photos. He also gained traction from the idea that people thought he was this mystery man, packed to the back teeth with charisma, sexual danger, built to entice women to their doom. He wanted people to talk about him, whether they were recoiling in fear or praising the ground he walked on. Most of these mad, slavering killers were the same – a fact that Margaret Wardlow, the 13-year-old victim of the Golden State Killer, recognised. Though Joseph Joe DeAngelo had well moved from the rape phase into the rape-and-then-murder phase, he didn’t kill Wardlow when he attacked her. Throughout her ordeal, she kept telling him, ‘I am not afraid of you’, ‘I don’t care’, until he fled, sparing her and her mother. She explains why:

‘He wasn’t getting what he wanted,” she said. “He wanted fear. He wanted to see fear in me.’

These men thrived more than anything on fear, on awe, on impressiveness – of being seen as monsters, cruel, callous gods. Look at Leopold and Loeb! They wanted to commit the perfect murder to prove that they were super-men, above the rest of the human race, even if that superiority made them beastly and horrific in the eyes of the public. Killers are the living embodiment of ‘all good press is good press.’

So Berlinger making a film that quintessentially says ‘look how horrible and sexy this bad man was’ does nothing to insult or bring Bundy down to size. Ignoring him, laughing at his essentially pathetic nature – because he was not the wunderkind of crime that people describe him as, he just killed in an era of police incompetence – that’s what really does a disservice to his memory. Focusing on the women he targeted, not as bodies or trophies of Ted’s broken brain but as how they were, what they were before him – students, warm smiles, a kind friend, a great skier, a fun older cousin who was always around to babysit, an intelligent prospect destined to go far, a caring young wife who spread lightness wherever she went – what they continue to be for their families and friends, unbruised and unblemished by his deranged insecurity, is the ultimate insult to his god complex.

So, in the alternate parts of the article, I was going to give you paragraphs describing the young women he attacked. Not as collections of insults, autopsy reports, posthumous degradations, but as living, breathing young women. Family stories, likes and dislikes, favourite vacations, arguments, pet peeves, future aspirations.

I spent four hours combing through newspapers, both modern websites and archival footage (thanks, St Andrews, for the subscriptions). And there was so, so little.

An absolute trove about how he killed them, his confessions, his ripe and vivid descriptions of raping and torturing and burying them. Of painting makeup on their severed heads. Speculations about how he snatched them – some particularly wild theories about him having spectral powers were the standout of that google endeavour – alongside speculations about, and I’m truly aching at having to say this, how long he kept them alive.

But about the victims themselves? B.B. – before Bundy – there is a dearth. There is nothing.

Apart from his first victim (of murder – it’s confirmed he assaulted and raped at least one young woman before this), Linda Ann Healy – who has a few paragraphs on her beauty, her life as a student in a greenhouse, her love for her radio job – there is such little information that it is practically nonexistent A few bylines about where they went to school, maybe. Donna Gail Mason gets a backhanded tidbit – she was more into smoking weed than going to class, it seems, and her friends didn’t worry when she didn’t turn up for a few weeks as she was a bonafide ‘free spirit’. Melissa Smith gets the honour of being ‘police chief’s daughter’. Nothing else. What there is about them exists only to further Bundy’s story. The facts don’t exist in order to just tell you about the women themselves. He got away with Mason because she was a free spirit – this facet of information about Mason isn’t there to put her down onto paper, but to explain how she ended up dead with her skull burnt to ashes (maybe – you can never trust his confessions) in Bundy’s (unknowing) girlfriend’s fireplace. Though their families will no doubt keep them alive and glowing in their memories, and though they have doubtless tried to talk to people about their daughters as living, beautiful beings, the press is just. Not. Interested.

The message is – killers are special. Different. Captivating. Worthy of conversation.

The girls are only remembered because they came in contact with a star.

____________________________

I will be the first to admit I was a morbid child. Always have been, always will be. My aunty bought me a book once called What’s the Worst that Can Happen? It had a little plastic red case over it, embossed with a bright white skull and crossbones. I think I was around seven when I received this, and I was obsessed with it. Each page – all glossy and laminated, with the sort of clear, easy-to-read black font that also looks a bit dangerous, a bit edgy, to both help its child readers along and make them feel suitably adventurous and grown up – had a scenario on it. Some were animal based – a blue-ringed octopus, a black widow spider, a stonefish – and some were random events – like a plane crash. Some were natural phenomena – I grew up with a healthy fear of avalanches for someone who lives in the largely snowless fields of South Wales – and some were totally bizarre, like the one that involved a certain type of eagle that drops turtles from a great height in order to crack their shells. Each of these pages outlined the scenario: maybe you caught a glimpse of a sapphire-winking mollusc glowing golden in a warm wet rockpool, maybe you were sitting on a Boeing that was flying uncomfortably low, maybe you heard an ominous, crashing rumble from the idyllic white mountains above you. Maybe you saw a weird, lumpy shadow circling far above that looked like an eagle with something (?) in its beak.

And then the book would tell you the sequence of events that would lead to the worst that could happen. Every paragraph would end with: ‘and you die.’

Cheery, isn’t it, for a seven-year-old? Thanks, Aunty Nic. You always did understand the potentially grim bent that beat itself, ghastly and red, in my childish heart. I am glad you nourished it on gothic tales – I quite like it, and it would’ve been a shame to see it die out.

So, picture this – young me, propped up with a duvet over my head, my nifty reading light (of course I didn’t have many friends, is that even a question?) in my hand, scanning over pages and pages of potential deaths for myself. You’re alone, on a remote beach in Australia. The sand is warm, and no-one else is in sight. In the water, see a sweet little octopus, glittering. You pick it up, and it wraps itself around your hand. You put it down, its bite so small that you do not even realise it has had you until your body starts to lock up. It has injected a venom powerful enough to kill 26 adults, and paralyse your heart and brain in minutes – this is called a neurotoxin – and as you collapse to the ground, you are totally conscious of the pain moving excruciatingly through your body, though you can’t open your mouth to scream. And you die. They always had these very incongruous little comments to go with these rather grim tales – ‘fun fact! One man, after being stung by the blue-ringed octopus, could not tell the rescuers who were working to save him that he was staring at the sun, nor could he close his eyes. Though he survived, he became blind from the sun burning out his corneas!’. I love those boxes, now, thinking of them. The absolute absurdity of it! ‘Burning out his corneas – exclamation mark!!!’. It sounds like the writer is taking absolute joy from the terrible, terrible ordeal of this man. How was that allowed to be published in a kid’s book? How did they miss that? Or was it deliberate gallows humour? Either way, it’s funny.

Or another favourite whose page was dogeared and thoroughly well-thumbed: you’re going for a surf off the coast of Monterey Bay, California. The wind and the waves are perfect, and you and your friend have planned this surf for weeks. (Bit bizarre, reader, that I was so scared of this one, considering I had never been surfing in my life and whenever I did see surfers on the beach in Porthcawl I thought they must all have been deranged to stand on a small plank of wood and throw themselves into what seemed to me 30-foot waves, and as a result of this derangement, they must not be very good company at all, and I would rather be caught dead than join them, but, I digress). As you catch a gnarly hangtip (I no longer have the book, and am relying on memory and my vague recollections of Nickelodeon programmes with happy, tanned looking kids for my surf lingo so please excuse if that isn’t quite hip enough), you can see a dark shape under the cusp of a clear surf. After seeing your vigorous movements, and because of the black oily-looking material of your wetsuit, a Great White Shark has mistaken you for a seal. It catches hold of your leg, biting it off from the knee down with its razor-sharp teeth, severing the femoral artery. Two things could happen. Either your friend gets to you in time and wards off the shark, carrying you back to shore. By that time, you will have bled to death. Or, the smell of the blood attracts a near school of sharks, who tear you to pieces in the water. Your body washes up several days later. And you die. The fun fact, for this one, if you’re interested, was ‘Fun fact! In 1981, Lewis Boren (yes, reader, I did have to check the names and dates but I remembered the story, so did it haunt me in my little pink bed, five thousand miles away from any potential great whites but absolutely shaking nonetheless) was found with a massive wound from a great white, stretching from his armpit to his hip bone!’

As you can tell, I was terrified by this book.

I was also exhilarated.

I had the absolute cheat sheet to life here – the manual to protect me from every possible death. After every ‘what’s the worse that can happen’ scenario, you see, the book kindly included a little section titled ‘What You Should Do’. Blue ring octopus? Don’t touch it, mate. Here’s how to identify it, so make sure you leave it the hell alone! (They didn’t say hell, I know, but I like the emphasis). If you are going rockpooling in Australia, bring a friend, in case you don’t mean to touch it but like, I don’t know, fall onto its stingers. That friend can get you to the hospital and save your life. I can’t remember what the advice was to avoid great whites, but you better believe I took it as gospel.

I carried this book everywhere. For a child that regularly left everything behind – lunchbox, bobble, cardigan, a single shoe one memorable time – this book was welded to my hand. I consulted it for any situation I believed potentially could end up in a worst case scenario. It was all I would talk about at dinner. My poor parents, bless them, waited until I feel asleep in the car and then disappeared the book somewhere. I don’t blame them. What would you do if your seven-year-old told you exactly the likelihood of you getting gouged to death by a bird of prey (in graphic detail) and how to avoid it? It wasn’t particularly healthy, despite my deep and unending love.

I haven’t forgotten about that book. Periodically I google it, trying to find a copy, but I must have the title wrong because I can’t find it anywhere. I remember the company also produced weird children’s miscellanies (another gift from Aunty Nic, and my introduction to Sawney Bean, the Scottish family of incestuous cannibals that inspired Texas Chainsaw Massacre) but I can’t seem to find any results from that, either.

When I search for it, I tell myself it’s out of nostalgia, a want to see the words on the page again, a want to laugh at my old nonsense, and, to be truthful, a bit of interest – I miss the encyclopaedic knowledge of deadly animals that book gave me. But, if I was really honest with myself, it’s because some part of me still wants to know. To possess that same cheat sheet, that same protection, the same promise to myself that I would know what to do if the worst happened. I would know how to keep myself and the people I loved safe. I could stop death – I could prevent it, protect them – because I had read enough about it to know what to do.

Now, even that book, wildly graphic and suspiciously bloody for children’s literature, didn’t include serial killers. I think necrophiles and cannibals and human-taxidermists (oh my!) might have been a step too far, even for them. But when I started reading about serial killers, I think I might have stumbled on a bit of a similar thing. It is a truth universally acknowledged that if you happen to end up a woman, your risk of ending up assaulted and murdered basically for the fact that you are randomly sexually attractive to some absolute creep doubles in likelihood. I had great whites and blue-ringed octopi and avalanches covered, I knew how to handle myself. But, on my spreadsheet to avoid death, the excel cell labelled ‘serial killer’ had a glaring empty space next to it under the heading what to do.

____________________________

Name me one victim. Of any killer – and not the sort of half-arsed ones like J.F.K or Martin Luther King – they don’t count because as far as we know their slayers were one-hit-wonders. I mean the victim of a serial killer.

I can think of one off the top of my head. Gianni Versace, shot dead by Andrew Cunanan on his luxurious cross-country killing spree.

Funny, how he’s a man.

And I’m immersed in murder – I read about it constantly, for fun, and for academic work. (My boyfriend likes to joke that it’s very fitting that the essay that I received the highest mark for in my university career was on Jack the Ripper.) I have ‘favourite killers’ – a facet of True Crime that is both common and weirdly grim if we stopped to think about it, like trading top trumps of sports stars, sort of half-heartedly justified in the sense that it’s not favourite as in you like them, but in that they’re most interesting to you. Some of my top ten include Robert Hansen (Alaskan killer who flew out girls in his private plane to the remote wilderness then hunted them like dogs. Sometimes he let them go, if they provided an entertaining enough chase); Ed Kemper (the co-ed killer, 6ft9 and an IQ of 145 – pause for a moment to play the song ‘Big John’ by Jimmy Dean, and sing it in the way he sings ‘6ft6 and weighed 245’ – killed young women before turning himself in after decapitating his mother and having sex with her detached head); Joseph DeAngelo (the Golden State Killer who broke into couples’ houses and could move with no sound, caught through DNA testing several years later); Gary Ridgway (murdered sex workers for nearly 20 years without being caught); Jack the Ripper (more for the foggy Victorian atmosphere than the crimes). I have least favourites, ones I avoid because they ping too close or they make me sad – Aileen Wuornos (hearing her try to describe the rapes and abuse she went through, and balancing that empathy with her coldblooded shootings of innocent men hurts my mind); the Toybox Killer (I read the transcripts of the tape he would play to the women he captured, and it was the first time something was too much for me); the Zodiac (I’m sorry, but he’s just boring, isn’t he? Like, we get it, you have to shoot bullets – phallic – into young couples to regain your masculinity and reassert your intellectual superiority with some funky ciphers but it’s just a bit meh when it comes to the brutality scale).

I can recall these details with frightening accuracy, when I think about them. They are just within the grasp of my mind, glittering there – I know that the detail that hammered Robert Hansen home was that he had a bracelet that was specially made for one of his victims. I know that the detail that broke BTK (the ‘Bind, Torture, Kill’ killer, also known as Dennis Rader) was the DNA collected from his daughter’s smear test. I know the detail that the Golden State Killer once stacked plates on the back of a mother while he raped her teenage daughter, and that he told her if he heard those plates move, he would kill them both. Drowning in gory, brilliant, detail, the portraits of these evil men are sharp in my mind, outlined in needlepoint fine relief.

And yet the victims – young women who often look like me, who might have thought like me, who conducted their lives in the same patterns that I do, going on dates, walking home from the cinema, forgetting to pull the curtains closed all the way, up until the fatal intersection they had with a lunatic – those victims, I can’t remember. Sure, I know the ones that I’ve referenced in this article, but only because I googled them. The only other one apart from Versace that I can remember off the top of my head is Eklutna Annie, the nickname given to a Jane Doe killed by Robert Hansen. I only know it because I’ve actually been to Eklutna. Perhaps it’s easier to remember a nickname than it is to visualise a living, breathing, registered-on-census person.

These men are the furthest thing from me in behaviour, lifestyle, circumstance, attitude – well, we hope so, Caitlin, you’re saying – but I know every single detail about their lives. The bodies that they tortured, bodies that look like my own, drift out from my memory as if none of us ever existed.

____________________________

I’m not going to tell you I have all the answers for why women like me consume true crime, why we memorise and obsess over the lives of men who, most likely, if they had the chance, would have eviscerated us. There are plenty of psychiatrical articles and think pieces out there conducted by people far more intelligent than I could ever hope to be. Fear is one motivation. Like my little red book, women want to be prepared for when the worst happens. We are raised with the constant and ever-present knowledge that at any moment a man – family, friend, stranger – could be looking at us with a view only of how he can best take from us. Edmund Kemper put words to our fear: ‘When I see a cute girl walking down the street, one side of me says, I’d like to talk to her, date her. The other side of me says, I wonder what her head would look like on a stick?’.

We know methods to avoid this by rote. Keep your keys in your fist, only go out in groups after dark, never let them take you to a secondary location. Avoiding rape and murder are two things that women are unfortunately raised to recognise like second nature, a bloody sword of Damocles swinging pendulous above our heads. But the thing is, is that women do all of the usual tactics and the bloody bastards still manage to keep killing, keep raping, keep taking. So, we adapt, learn new stories, find new chinks in our armour to cover and protect and gloss with titanium. We do that by studying the stories of our sisters that weren’t so lucky.

Edmund Kemper, the co-ed killer, murdered his grandparents at age 15. He was then placed in the criminally insane ward at Atascadero State Hospital. Now Ed was a bright young boy, for all the murderous intent that lurked behind his huge and unwieldy body. In fact, most people argue that he was one of the most intelligent serial killers ever measured (not a stand-out achievement, considering most of them are dull as a bag of rocks). Ed spent hours and hours in group therapy with the most depraved and dangerous rapists and home invaders, at the tender age where sexuality buds and we develop interests and obsessions. Already prone to violence (remember, the whole killing-of-the-grandparents thing), Ed’s young sexuality, exposed not to normal relationships between consenting adults but only to sordid tales of violation and graphic assault, understandably became distorted and brutally sadistic. And here’s where his intelligence comes in. He listened to the tales from these predators, and he took notes on where and how they got caught. The biggest lesson, he said, was to never leave a victim alive to testify.

So, in a way, we’re all Ed Kempers as much as we’re all Aiko Koos, Mary Ann Pesces and Anita Luchessas, Cindy Sharpes and Rosalind Thorpes, Alison Lius and Sally Halletts, as much as we’re Clarnell Strandbergs. We’re all learning from deranged, violent men.

Another reason usually given is a love of fear, the same motivation behind the reason we love horror films and scary books (I am, by happenstance, a big fan of both of those things). We dive into the Golden State Killer and struggle to sleep, holding our breath at every jangle of the window, every creak of the floorboards. We revel in the misty terror of the Michigan Murders, of the roar of a motorbike and the still, grassy resting place of mutilated bodies. With articles every which way proclaiming the death of the serial killer (their golden age is generally recognised as 1969-90, as pre-boomer and boomer men who had either been to war or been raised by the emotionally damaged parents who had lived through it released their wild and rampant rage on a world that had little concrete police procedure and no DNA tracking capability), perhaps on some levels the fear of serial killers has become as distant as the scream of a supernatural entity. It’s a safe fear, psychiatrists argue – a fear that is close enough, real enough, to deliver that adrenaline shot (the good stuff) that lets you know you’re alive and beating, but also distant enough, also that-couldn’t-happen-to-me enough, that it is a soothing rather than disturbing dose of fright.

As you may have noticed, those explanations contradict each other. Either you are afraid of serial killers because death and rape is a very real and very present possibility for women, and binge on true crime to protect yourself from them, or you are afraid of them but in an abstract way, as people are scared of ghosts, because you believe that the killing and the raping could never really happen to you. Maybe those contradicting beliefs can live comfortably in your mind, as George Orwell so confidently argued they could. Maybe they can’t.

I think there’s another reason. Another reason that is usually described as ‘compassion for the victims’. I think that’s true – you can’t listen or read these graphic and brutal tortures carried out on their bodies without imagining their fear, their tears, their desperate need to survive.

One of Karla Homolka and Paul Bernardo’s victims, 14-year-old Leslie Mahaffy, told them – after hours of assault – to retie her blindfold because it was slipping, and she didn’t want to see her attackers. That girl knew and tried every which way to prevent them from killing her, she was so smart, she was so desperate, desperate to live. Maxine Zazzara, after witnessing the shooting of her husband and being beaten and bound, undid her ties and retrieved a shotgun from under the bed and attempted to disable grinning, bloody Richard Ramirez. The shotgun was empty, despite her frantic, brave desire to free herself, to end the terror. The surviving victim of David and Catherine Birnie, seventeen-year-old Kate Moir, broke a window lock with her head and ran, half-naked and bloody, through a yard with an attack dog to get free. The only difference between those three victims, the difference between dying and surviving, was luck. They were all equally courageous, equally determined, equally smart, but one got away with it and the other two didn’t. You can’t consume information like that without aching in every part of your body for them – but I think compassion doesn’t fully encompass it.

The thing is, we, as a society, are obsessed with female death. We have been for centuries, if not millennia (my knowledge of history goes back to around the Tudor times, and alongside a bit of Celtic Welsh, but nothing before that because it’s just rocks and fights, right? Boring. So take millennia with a pinch of salt). It’s everywhere – in luminous pre-Raphaelite paintings of white-faced ladies with blue lips in boats filled with dying roses, in Dante ramblings about child-loves found pale and still, the infectious diseases that carried them into the grave miraculously gone, leaving them blemishless, bloodless, beautiful. In Tristan and Isolde, in the sacrifice of poor, unbloomed Iphigenia in the Iliad. In purple-veined Annabel-Lee, sleeping beneath her marble tomb, in the mirrors in the eyes of Mrs. Leeds, in the ghostly young woman covered in sea creatures in Dark Shadows. Death, again and again and again. There’s nothing prettier than a dead woman.

Obviously, there are conditions to this – the girl has to actually be pretty (which is why we hear more about the victims of Ted Bundy, who are young and fresh and have nice, clear, well-maintained skin, than we do the victims of Harold Shipman, who were old and thus did not have lovely, large, liquid eyes and youth-full lips for us to moon over). She is only talked about when she is fresh-dead, her skin still soft, when the rot hasn’t set in. When the only sign that she is dead is the lack of the life-blush beneath her cheeks and in her mouth.

When she isn’t breathing, when she isn’t moving or wriggling or rebelling, she is beautiful.

Gabriele D’Annunzio, the Italian dickhead who basically invented fascism, put it so well in his letter to his first girlfriend, Giselda:

‘I would go around all the florists in the city, fill a carriage with assorted flowers, just to bury you beneath them. Yes, to bury you, I want to make you die.’

So, we’re used to it, the idea of the blessed dead Damosel.

Ted Bundy became a folk hero in the U.S. for a long, long time (if he still isn’t now). He escaped from jail, twice, and had people up and down the states rooting for him – even adapting Native American songs to make him a hero of the west. But when he was executed, crowds burbled out into the square around the jailhouse, holding luminous signs exclaiming ‘Fry, Bundy, Fry!’ ‘I like my Bundy well-done!’ ‘Tuesday is fry-day!’.

There are theories about why this change occurred – how the public could go from adoring him to baying for his blood. Some argue that people didn’t believe he was guilty. Jane Caputi argues that many people – many men – did know he was guilty. And they respected him for it. They admired him for carrying out a desire that so many of them kept, nurtured, raw and wanting, in their good-old-American-boy chests. Ted Bundy was like them – he looked like them, he was from the same background, he was training to be a lawyer, he was a rising star in the local Republican party, he went to church (a Mormon one at that – that fundamentally American endeavour that is Mormonism). He was handsome, charming, well-connected, middle-class. He was them – he said it himself, so many years later: ‘We serial killers are your husbands, your sons’.

And the women he killed were not vulnerable sex workers and runaways, transients American men would only see briefly when their driver took them through the wrong part of town, or when they watched a gangster movie. His victims were their own girlfriends – tan and young and pretty, co-ed girls that they thought were out to get a M.r.s rather than a B.A. degree. They summered in Cape Cod and Long Island – they were clean and neat and would be great homemakers. They were depicted in the press as girls that the middle-class men of America dated on Sundays, went to formals with, partied at keggers with. As a result, Caputi argues, American men identified with Bundy, who had done what so many of them were taught to want – albeit unconsciously by films and books and history – who had taken anyone’s daughter, anyone’s wife, anyone’s sister and murdered them. He was a hero! An outlaw! He had gripped the American Dream in his hand. As his former co-worker Ann Rule describes, he ‘achieved the status of Billy the Kid’. That’s why he remains in our consciousness as much as he does, more than men who committed crimes similarly or even more so horrific in nature, more than Gary Ridgeway (targeted sex workers and strangled them, before weighting them down to a bloated death in the rivers of Washington State) or Robert Pickton (also targeted sex workers and fed them to the pigs on his meat farm) or Robert Hansen (you know him, my favourite murderer, the hunter). He did what American men of certain means, wealth and opportunity wanted to do. He did what Christian Bale did in American Psycho (and god, don’t tell me you don’t know at least eight young men who glorify Patrick Bateman).

In a way, women glorified him for the same reasons – flocked to the courtrooms and dyed their hair and pined over him. The same way some women – hybristophiliacs – lust over and romanticise Richard Ramirez, Jeffrey Dahmer, the Columbine shooters. I have been on some of these forums – I wrote a story about a school shooter for Year 11 English once (Mrs. Williams, if you’re reading this, I am so sorry), and ended up on one by mistake, looking for some more information on the timeline of events in Columbine. And these women worshipped at the altar of Harris and Klebold. They sobbed for them, they ached for them, they yearned for them. The same way that women who married convicted serial killers and child rapists in jail yearned for their own imprisoned annihilators. People speak about these women with absolute derision and disgust, and I get why – it is an awful, and largely incomprehensible thing. But I believe it is also missing the point to vilify them this way. Often, many of them are young – often, many of them have severe mental illnesses that are co-morbid with their hybristophilia. They also have been socialised, for a long time, to think that it is the most natural thing in the world for a man to want to punish their body, to want to rip them apart. To them, every man is thinking it – it’s only the bravest, the realest, the most machismo men that make it happen. Perhaps, that belief, that inherent recognition that it is the natural order for men to want to hurt women is the belief that needs to be most examined when we so quickly deride these strange, and I’ll admit, on the surface, repulsive women. It’s also interesting to me that all the stories of men treating Bundy like some kind of Jesse James hero, a raping, murdering Robin Hood, disappeared quite quickly under the carpet. We call out the women who glorify them with a fury to rival the avenging sword of God, but the men who did the same – the men who wanted to have a beer with Bundy instead of fuck him – those men are quite quickly forgiven, excused, forgotten. Interesting.

But, I digress. Bundy was a hero to thousands of young American men. Why else, when Bundy was on trial for the rape and murder of Caryn Campbell, a young nurse who took a trip to Aspen with her cardiologist fiancé and his two children and disappeared after she went to retrieve a magazine from their room, did radio stations have a ‘Bundy hour’? Why else did men make jokes about attractive young women who walked by about wanting to ‘Bundy them’? Why else did restaurants serve ‘Bundy burgers’? The same men who chanted and bayed for his blood at his electrocution empathised and identified with him at first, even when the FBI announced that he was wanted for thirty-six sexual slayings across the US, involving rape, necrophilia, and torture. They revelled in the fact that he did what they wanted to do. As Jimmy McDonough so eloquently put it: ‘Most men just hate women. Ted Bundy killed them.’

Their empathy started to fade, replaced by derision and disgust, not when the details of his murders came out, not when he was caught, not when he was sentenced to death – not, to make it obvious, when it was clear that he was responsible for the multiple and atrocious killings of at least thirty-six young women. The empathy dissipated, as Caputi describes, when Bundy himself admitted his guilt. When he admitted what he’d done. When he was honest about his fear of death. In this admittance, Bundy made those killings, that want-to-kill that he had earlier justified and heroized in so many men that witnessed his exploits, made that desire that he so embodied, made all of that wrong. By confessing, he made his murders a crime, a misdeed, a violent and evil thing. And thus, all of the men who had made the Bundy jokes, who had listened to songs on Bundy hour, who ate Bundy burgers – it told them that they were wrong too. And, well, we can’t have that.

As Caputi so eloquently describes, Bundy thus became a scapegoat. A man with which they could load up their sins. Bundy could take the collective want to murder-rip-tear all those lovely dead young women and bury it with him in the ground like so many poisonous nuclear leftovers, waiting to spring up as fetid and mutated plants. He could become a repository for the societal obsession that lurked, and when that body was fried, up in smoke alongside it went that cursed and grotesque thing, that longing for a pale, speechless, limp young woman at your feet.

I’m not saying, before I get the Reddit droves on my door (and no shade to Reddit, because I love it and it has opened my eyes to sides of political discussions I have not considered before, and sides that I revile but think necessary to read because you know, know thy enemy) that all men are raving murdering sex maniacs who want to go full Bundy on any young women they see. I don’t think that that is a widespread and terrible issue beating in the hearts of all our sons/brothers/fathers/husbands. What I do think is that through eons of collective fetishisation of freshly-dead young women – who symbolise the very attributes of glorified femininity touted by tomes and thinkers from the Bible to Luther to Ben Shapiro, submissiveness, mouldability, silence, beauty – there has become a grudging understanding? Respect? Fascination? With the men who carry it out. What makes them different from us? How did they read and consume the same history, materials, ideas as we did – but act on it?

And for young women, the baying hounds of the true crime community, I think we get some unconscious fulfilment by listening to these crimes. We have always known that this could happen to us. That it is a possibility for us. This fact is horrifying and frightening and totally obscene – it keeps me up at night with fear and worry and disgust. We seek to prevent it, avoid it, pray to the God(s) above to keep us and our sisters and our friends safe from it. But we consume the same media that they do. We imbibe the same subconscious romanticisation of Ophelia, of Juliet, of Marilyn Monroe, of Laura Palmer. It is a troubled romanticisation – overwhelmingly white, for one, and focused on traditionally ‘feminine,’ thin bodies – but it is one that is still there. We empathise with them – not just as people, as fellow women, victims of the same monster we have been trying to avoid all our lives – but as those who lived up to the literary and filmic and historical icons we have been hearing about our whole lives. They are beautiful, dead, young things. They are what we were taught to want – the stuff of Sad Girl music, the stuff of e-girl dreams, the stuff of Hozier’s In A Week. On some level, we perhaps feel envious of them – not because that is right, nor do I think it is a conscious choice. There are lots of things that society has subconsciously conditioned us to feel that are absolutely morally reprehensible and that the vast majority of us would revile and repel in our waking thoughts. Like when you see someone and your first thought is fat. Or slut. Replace those with any disgusting and reprehensible societal norms and conditions that we didn’t start interrogating until we hit our teens. As soon as you think it, it makes you sick – your next thought is where did that come from? Why did that happen – why did I think that? I am vile! The first thought was not you – it was not your inherent evil, but the plume of indoctrination that sticks out of your brain like a feather. We all have one. What makes you morally good (or morally evil) is if you interrogate and repudiate those thoughts, work to dismantle them, or not. So, when you see Bundy as Zac Efron and he stalks a girl, if your first thought is sort of attracted, or when you see lovely Laura Palmer dead and gone and your first thought is some muted longing – that’s not you being a freak, or evil. I think on some level, it is just what we have been taught to admire. To aspire for.

It is also somehow weirdly satisfying – that’s not the right word, but it’s the closest I can get. Like poking a bruise. Like seeing the red water from a shaving cut. Like burning a thumb on the curling iron. I have written on the death drive before, I have written on the self-destruction drive before. I don’t agree with Freud on a lot of things (emphasis: a lot of things), but I do think he was right about our inherent need to go hurtling along the track towards oblivion, towards decimation. It’s easy to fulfil that drive, as a young woman. Stick on My Favourite Murder, or crack open any book marked ‘true crime,’ and normally, you’ll find yourself dying. Over and over. Any way you might conceive of – someone who looks/thinks/is, on some level, you, has kicked the bucket. Itch scratched. Job done.

That is where the tension lies, you see. The string-bow of pain that young women are taught to tiptoe across, fearing the black water below. On some level, we listen to true crime because we are terrified, because we want to avoid every possibility that we could end up dead and raped and hurt. On some level, we listen to true crime because some terrible, conditioned not-us part of us longs for that pale, beautiful shell of oblivion. And the line we walk on – the middle ground – is because the victims we read about are us. We see them. We are them. They are both us now and what we could be, if the worst were to happen. Like In Cold Blood, our bodies – how they are killed, and the acts committed upon them before and after death – are the most interesting parts of the crime, them and the men that decide to tear them apart. We listen to how we screamed, how we cried, how we looked from the inside out. We are obsessed with our destruction – preventing it, and looking at it. Poking the bruise. Examining the red water.

It is terrifying. It is beautiful. It is a mirror.

As Edgar Allen Poe once, horribly, said: ‘The death of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world’.

And all young women are, in some way, poets.

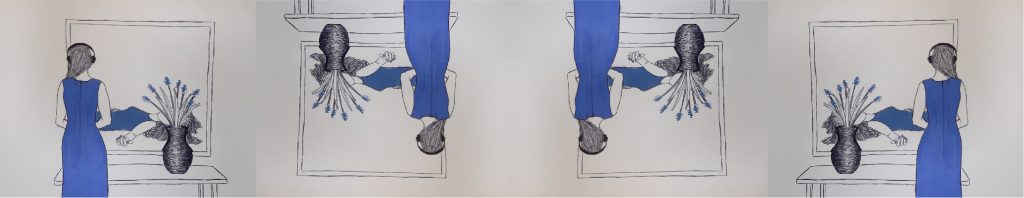

Art by Kate Grant