Age five: I stood before the mirror and gripped the soft flesh of my stomach and a part of me longed to cut it all off, for reasons my childish mind could not grasp.

Why?

Age twenty: I stood in the shower, ugly gasps tearing bloodily upwards through my throat as I gripped the fleshy parts of my thighs, the bottom swell of my stomach, the soft parts of my upper arms.

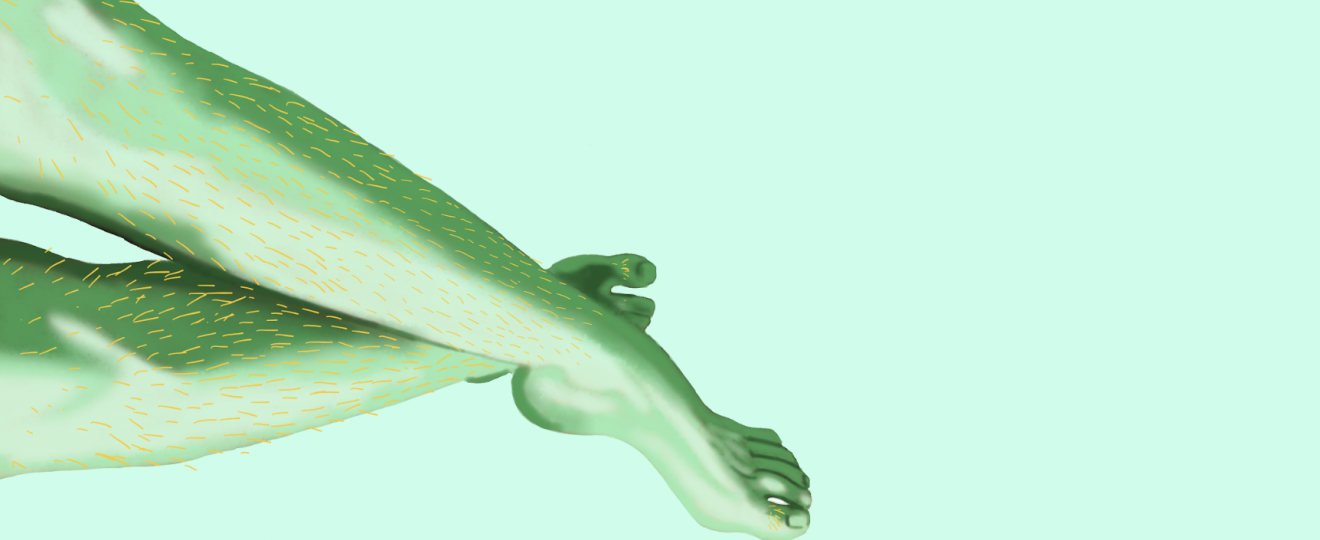

‘I hate you; I hate you, you’re wrong, you’re all wrong.’ Every time I caught sight of the wholeness of my body, the curve of my legs and the spider web stretch marks and the paleness of me I wanted to take a scissor to the different parts and cut them all off.

I felt it stronger than I could breathe.

Why?

In 1927, Sigmund Freud (father of psychoanalysis and generally regarded as a bad guy) calcified a trend in psychology that had been brewing for a while: Drive Theory. According to Freud, the human being has only two universal functions, biological and mental primary motivators for existence: Thatanos/Death, and the secondary Eros/Life drive, which, though discussed by Freud, was crystallised and coined by Freudian-taught psychologist Wilhelm Stekel. Eros was a drive for life, summarised by Freud as the desire for sexual copulation and reproduction, redefined after wider study of sexuality and asexuality as the desire to live, the survival instinct, the desire to experience, cultivate and above all else, survive. Like a flower that grows thorns, everything we have built as a species, knives and social skills, atom bombs and tea sets, has been designed in order for us to deter predators, kill off threats, form security-ensuring pack bonds, all with the ultimate goal of keeping ourselves breathing for a moment longer.

His theory of the Thatanos Drive was the complete opposite. A desire to seek death and oblivion. One can suggest that these two drives fall into the quintessential, knuckle-tattoo dichotomies; love and hate.

The existence and manifestations of the love drive are not totally selfish—procreation, libido, survival, pleasure—but can also bloom into glorious displays of love for humanity in its multiple, myriad states. The love/life drive is the basis of our social cooperation, of our empathy, our kindness. When you bring your mother flowers to make her smile; love drive. When you bake your friend their favourite treat because they’ve had a rough week; love drive. When you compliment a stranger on the street, just cause; love drive. It seeks survival, and that survival cannot exist alone. It is a desire for the life of the human race at large, not just the life of the self, as the life of that self is necessarily dependent on the life of the species.

The death drive, on the other hand, comes from a place of sheer frustration at existence, and the lack of control we have in the circumstances of that existence. Others have proposed it is a natural means in which to stop the human ambition for immortality, an inbred mechanism of population control. It results as an inward self-disgust that leads to behaviours designed to masochistically punish and harm ourselves, hastening death; such as reliving traumatic events, engaging in decidedly unsafe behaviours (taking knowingly harmful drugs, smoking, unprotected sex), and perhaps more studied in our current epoch, opening ourselves up to relationships despite recognising them as damaging, painful and toxic.

In the same way, as our love drive is a product of a universal love for humankind, the death drive manifests as hatred for humanity itself, resulting in aggression, violence and antisocial behaviour. The time when you said something deliberately callous or backhanded to a friend for no particular reason, the time you told your parent you hated them and revelled in their pain, even put the carton back in the fridge with only a sliver of milk left in the bottom; all manifestations of the death drive. Freud used the example of his interactions with World War I veterans who continually re-enacted or discussed battles that had been particularly inhuman or painful. The subconscious also fulfils these drives; Freud referred to examples of sexual fantasies and pleasurable dreams in serving the purpose of Eros, and nightmares of surreal and distressing events to fulfil Thatanos. The human thrives on these two drives; the need to survive, and the need to die. Though we all possess different levels and extremities, Freud believed they were a universal psychological experience.

In 1975, feminist film scholar Laura Mulvey took another of Freud’s theories and applied it to global media consumption, via the cinema. Mulvey used Freud’s concept of the male/active and female/passive (in that the male is the creator of meaning due to his possession of a penis, and the female is the receiver of meaning due to her essential ‘lack’ of one) in order to explain the inherently patriarchal usage of film to convey sexist ideology in order to support a distinctly unequal society.

While the main impetus of Mulvey’s Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema is the concept of the male gaze (women are forced to watch and receive meaning and story through the perspective of men, whilst men have their position as the creator and dominator within society and their right to the female body reinforced) her explanation of the manifestations of that male gaze is exemplary in its breakdown of Freudian psychology.

Due to an innate male fear of the female lack of penis, or ‘castration anxiety’, the male conspires to necessarily subjugate the female through the filmic medium as a result of its popular and instructional capacity. To understand this unique educational capacity, we must look at the work of fellow film theorist Richard Dyer. Dyer suggested film possesses an educational quality through its promise of ‘Utopia’. In filmic narratives, the characters often finish in a position of euphoric and right happiness.

We, as the audience, internalise this, and thus develop the idea that if we follow the behaviour of the characters within it, we too will achieve this Utopia.

Film’s utopic educational quality is indubitably and obviously dangerously, especially, as Mulvey suggested, in its ability to define the experiences of women.

To ease this castration fear and indoctrinate the submissive position of women in society, the male character/male-driven narrative of film often either dominates women, especially the ‘active’ woman, through abuse or through marriage/motherhood (think romantic comedy narrative: the self-assured, caustic, independent woman will invariably end up in a happy heterosexual marriage, sacrificing her principles of self-determination in order to rely upon and foster the male character), or it seeks to murder them. The advent of the camera and editing techniques allows the narrative to aesthetically dismember the woman, make them a consumable force, akin to a bite of tender meat on the prongs of a fork. When the woman is dismembered by the camera through close-ups, she ceases to provide a threat as the bringer of castration. She is destroyable, eatable, by the male. If we think of the close-ups that focus on the sexualisation of the female in a standard film, we see the destruction and separation of the whole form by focusing on segments of the leg, the torso, the hips, the chest and shoulder area, the mouth. The consequences of this are clear– females cease to be valued as a whole being. In order to possess the woman, you must destroy her. It is no coincidence that the body parts cut up through the lens were the body parts severed from Elizabeth Short in the infamous Black Dahlia murder, a crime twinned with the rise of Hollywood and the classic film so dissected by Mulvey.

Mulvey suggested that as such women who watch film must either masochistically identify with the female and consume the ideology of destruction and subjugation by nature of their gender, parroting, internalising and adhering to this narrative of female subservience (think #idontneedfeminism or the phenomenon of ‘I prefer to hang around with guys, as there’s less drama’), or they must both sadistically (and again, masochistically) identify with the perspective of the male character/narrative and take pleasure in the domination and dismemberment of the female character on screen and as such themselves.

This sadomasochistic/masochistic enjoyment recalls the very self-driven hatred that Freud first elucidated in his Thatanos drive. However, I would suggest there is a third, uniquely female-identifying drive, that while related to this death drive is distinct in its manifestation.

As a result of the natural psychological desire for death combined with the narrative of female destruction and dismemberment we experience as a result of our media consumption, both filmic as Mulvey described, and more recently through the format of social media sites such as Instagram and their distillation of women into hair, eyes, lips, chest, stomach, legs, within the female self a third drive has been fostered: the desire for self-destruction, or dismemberment.

When I was a young child, and still in the development of my adulthood, I have vivid memories of staring at myself and my body, determinedly grasping chunks of my flesh and having the desire to physically rip parts of myself off. It is the perennial image that circulates Facebook in search of a few sympathy likes, shared by those who feel an uneasy, rageful recognition of that feeling and want to discuss it, yet are still frustratedly beholden to the same ideals that creates it; the little girl standing in the mirror, holding a scissors to her belly rolls. I believed that this was both a sensation both normal and peculiar to myself; with my body the way it was, why would I not want to destroy or remove parts of myself? That wasn’t unusual, needing to change the way my body appeared. But it was rather a solipsistic experience, something done in the secrecy of a bedroom mirror or in a changing room at Topshop. I had never shared it with another woman; never thought to. I never believed it would be a shared female phenomenon yet, at breakfast with a friend, Rebecca Jonas, we were discussing the unfair limitations placed on women in regard to the body aesthetic, and suddenly she placed that lonely, consuming experience into words.

‘I’m not sure if you’ve ever felt this,’ she said, reaching for her drink across the table ‘but I clearly remember having a visceral desire just to grab chunks of myself and just tear them from my body.’ Going home, the concept would not leave me. I had conscious, near memories of doing that same thing. Gripping parts of myself, my thighs, my stomach, and wanting to cut them away from me. A ridiculous desperate urge to split myself apart. Speaking to more of my female-identifying friends I found the experience was a conscious and repeated one. ‘I’ve never thought about it, but yeah I remember wanting to do that.’ Yet, upon asking male-identifying friends I received blank stares.

‘Why would you ever want to do that to yourself?’

Why, indeed. Why is there an innate urge in women to rip and tear and pull themselves, more than anyone else, apart? Freud believed that the main manifestation of the Thatanos drive was physical aggression towards others, and an aggression towards the self in the form of secondary or eventual self-harm; drinking to oblivion, sabotaging self-opportunities, etc. Perhaps this description is one suited to the manifestation of the death drive in the male, but years of societal conditioning, illuminated by Mulvey and catalysed by the rise of instant realist visual imagery (film, photography, social media), has resulted in a communal female experience of the need to destroy oneself through the process of self-fragmentation. One need look at any mainstream film, or the multiplicity of porn both explicit and suggested in music videos, advertising, Instagram and television, and become conditioned to what a woman is and should be. They are almost never whole, undissected beings, rather existing as a pulled-open thigh, a dewy cleavage, a pair of sex-red lips. We are taught that the woman exists in separate pieces. How then, do we understand our realistic form as a complete physical being? There is a subconscious feeling of wrongness in the experience of the female body as a whole, connected self; something that our post-Lacanian brain doesn’t recognise as valid.

Indoctrinated from the mirror stage to believe that we exist in fragments, our subconscious fights to mirror what we have been instructed is the ideal female form. Think of the high prevalence of eating disorders in women, the skewed proportion of female self-harmers, even the increased likelihood of self-deconstructing behaviours such as trichotillomania and dermotillomania in women and it is clear there is an epidemic of self-dismemberment. We have identified too strongly, taken the message of patriarchal film too literally, pulled the lever of our death desire into overdrive and set about picking ourselves apart into the pout of Meghan Fox’s disembodied mouth, the splendid alien curve of Marilyn Monroe’s leg, the terminally circulating, endlessly undulating, cycle of Shakira’s hips. It goes beyond the desire to achieve the reproduction-serving sexuality of the Eros Drive. It is a result of the belief that our bodies are naturally meant to be deconstructed as it is all we have ever seen. As a whole shape, our bodies are unfamiliar and assumed incorrect. Imagine, for instance, the octopus.

Throughout our upbringing, we have been shown footage of what an octopus is and how it aesthetically appears; eight leg-like appendages attached to a bulb-shaped head. We have seen different sizes and colours of octopuses, but the basic anatomy of them remains the same. Now imagine you have been taken to an aquarium. You are shown a creature with six legs, a dorsal shaped head and fish-like wing motors, and you are told that this is an octopus. Would your natural inclination to believe that every piece of footage you have watched and every piece of knowledge you have received up until that point on the octopus was wrong, or would you be more inclined to say that this new creature is definitively not an octopus? It is far more likely that of the two, the second reaction would be the case. Relating this to the body, if the majority of our medial experience of the female body is of it dissected and dismembered for the reasons that Mulvey elucidated, subconsciously we have internalised that this is the way the female body should and does exist.

Thus, when we look or experience our own bodies, which exist in a whole, un-dissected state, there is an innate sense of wrongness, of untruth. We have been taught that a body exists separately, thus the existence of our own body as a whole feels inherently incorrect. We are unlikely to question our life’s worth of education, and since questioning or denying of ourselves as bodies in the vein of denying that the other creature was an octopus would lead to an identity dissociation crisis likely incompatible with the life drive, we attempt to make our body resemble those we have seen, those we have internalised as what female bodies themselves are. This is evidenced as the rise of social media places more and more pressure on men. As pictures of dissected abdominals and back muscles begin to bloom on Instagram, we have seen a rise equally in the prevalence of male eating disorders and self-harm behaviour in younger boys; those who have grown up receiving their education of the male form through social media platforms and films that are increasingly growing to focus on the male body as a dismembered existence.

This desire to dismember is a direct result of the combination of a media culture that values the sexual promise and lack of threat of individual body parts at the expense of a whole, and a subconscious that is vulnerable both to ideology and naturally pre-disposed to self-hatred. The origin of said uniquely deconstructive media is something potentially more difficult to unravel. Clearly it is the tool of a patriarchal desire to subjugate woman, as elocuted by Naomi Wolf in her seminal Beauty Myth. Is it too the product of a capitalist culture that values the individual parts of a person in relation to their productive potential over the whole integrated self? And perhaps most importantly of all, how can we seek to overturn this practice, both in formal aspects but also in its historical ingratiation into our media experience? Would it mean the death of the close-up? Or as Mulvey suggests, the death of narrative film altogether?

Whatever the answer, it must be implemented soon, before the wider implications of this medial-born impetus leads to us ripping ourselves apart altogether. Before the Thatanos Drive tips the scales and its physical effect consumes the balancing power of Eros. Before we all pick up the scissors and cut ourselves, and the world around us, into broken, pale strips of paper.

art by Sadie Loeber