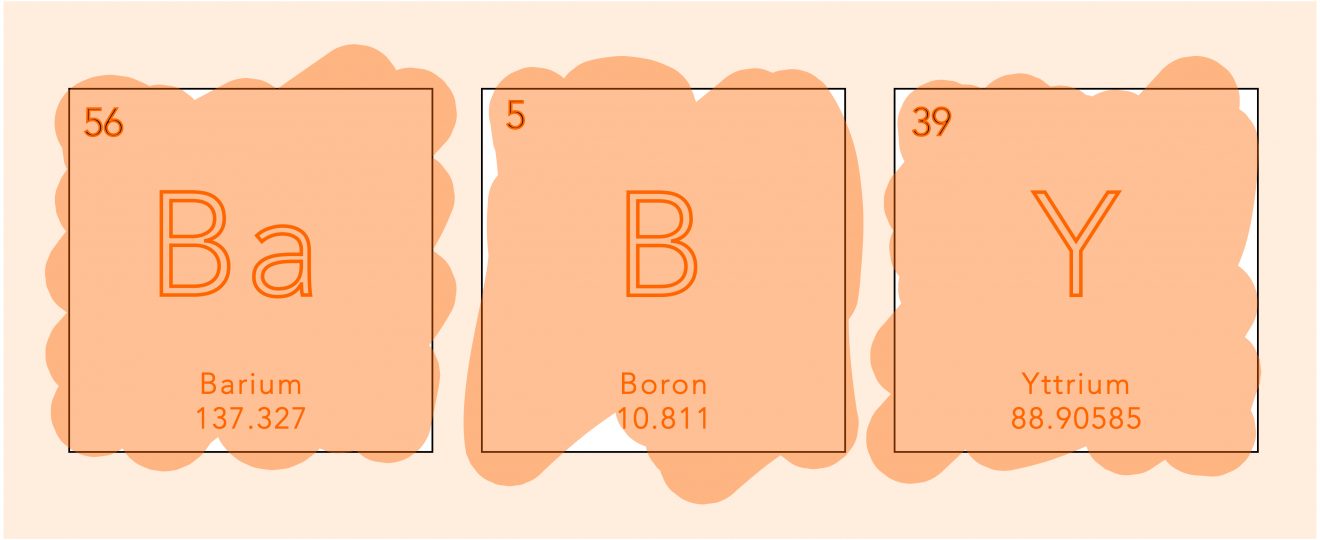

(BaBY)

‘Congratulations to the new parents. Can’t hardly wait to see the new arrival.’-Ernest Lawrence in a letter addressed to Enrico Fermi at Chicago University after his success on 2nd December 1942 in creating the first man-made self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction.

He’s reading. He’s reading.

He promises. He. Is. Reading.

Lilli had been at him to read this and so-so-that’s what he’s doing.

(and the white curl of the book’s paper skin around the humid not-damp not-dry of his finger when he turns the page is like petals, and it is as if in every paper, or essay, or play, or romantic comedy that he is sure she doesn’t even like but just tells him to read to see how far his love gets along the alphabet, it is as if in all of those words with every page he pulls back he is also pulling back a bit of her fuss and curls and lab-coat starch, getting a little closer to the brown and honey-crusted wet stamens of her brain, the pollen-sneezed anthers of her blood-flushed heart)

Did he mention he is reading?

It’s just. The swaying. With every shudder of his eye across the letters he can see it just there, just there. The dangle of the mobile rope, the catch of the silver and shapes as it twirls and fragments in the edge of the moon. Just soft. Just there. The wind catches the rim of it, and it curves, ducking and dipping, the little bumps of wood and metal knocking against each other. Dah-dah, dah-dah, dah-da.

He is reading.

But sometimes it’s the glow as well. He knows that it hasn’t got that ethereal, dewy effervescence that he always imagines, the spilt-peach luminosity of the sun trapped in metal glass refractions. He knows it doesn’t have that because that is what he dreams it has, and dreams, he knows, are an expression of the absurd. In those dreams it is always in aloe-spikes, stalagmites (or is it stalactites? He never found out the difference between the two, and now felt it too late to ask) pushing through the ground. It isn’t green the way pulp comics and diagrams tell him it will be. It is pink and orange, warm colours. It does not hurt to touch it, like he knows it would. It makes the tips of his fingers pleasantly hot. It feels like skin. It is not cold as crystal, glass-hard. It dimples under the pads of his hand, like Lilli’s thigh. He knows that that feeling wouldn’t happen, that if he touched it his skin would blister and pock and he would probably vomit and Lilli would hate him for having to scrub sick from his jumper, true, but his hands itch to peel back the sparkling surface of metal anyway and dip in. Take its stubby fingers in his own, print to print. Whorls melting into whorls. Rock it. Feel it settle into his chest there, palm to muscle. Seep in. Kill him.

Sometimes, when he thinks of it, he dreams that Lilli is beneath him, the soft folds of her coat—the dark, cranberry tweed one she wore on their first date, with the too wide button holes that her fingers fiddled with, the one pinned by the silvery brooch from her grandmother, the brooch that threw orange from the streetlights (then) and the desert sand (now) onto the curve of her neck—spread open like an arrowhead drawing flight path lines from the underside of her ear across her clavicle to lift off over her chest. And he puts his hands there, in the dream, on the edge of that coat collar and he pushes it off her shoulders and it spreads like blood or lit strontium chloride under her back and then when he touches her chest where he knows the ribs bend upwards to support the skin when he touches her it is like her skin cracks and inside the hollow where her heart is he sees it there, the glow, the orange liquid-crystal protruding up in their shards to meet his hands, the same silvery brightness as her smile.

It doesn’t have that glow, obviously, but the glint of the metal in the purple of the night makes him think of that thudding, pink-violet nestled in its centre. It must be lonely, in the warm rust of its cradle. The rope swings a little bit more. Some part of its coat bumps into the wood of the table. Dah-dah, dah-dah, dah-da.

He is reading. He knows why Lilli would like this. Parker’s wit is acerbic, and she has the same snark at the corner of her mouth that Lilli gets when somebody tries to explain something she already knows to her. He can imagine her laughing, the rumple under her nose above her lip. She would laugh if she knew what he was doing now. Of all the times. She would say. Of all the times. She was very much like J. in that respect. J liked her, he knew, thought she was funny and bright. She was funny and bright. When Lilli had arrived with him, they had tried to put her as a typist. It was J. who fought for her to take a scientific test, and when he saw her skills (in truth, better than Donald’s) he fought again to have her included on the chemistry floor. They had similar minds. Cellular bridges crossed in an eye flicker. He wasn’t on the floor here, much, but back at the beginning he would sometimes take a walk through the chemistry department, and it was her he would stop to talk to on his way through, and Donald only by proximity. He used to say that the colours and the swollen eyes of test tubes made him feel like he was in a kaleidoscope. It was refreshing, apparently. Helped him get the joints of pink and green and blue in his mind to click into a new pattern.

It made Donald queasy, all the smells and the chalkboard shavings of equations curling their white lace down his throat. Too hot and strong and brilliant, the air thick with burnt-toast dirty hair of the chemicals. It made him itch and every breath was thick and dirty and didn’t feel clean, pricking and popping blisters under his skin till he wanted to peel it all back layer and layer till he was red pulp and white bones and two bright eyeballs.

When he felt like that he wondered if this was right. Stared out of the Perspex cheeks of the windows at the tangerine sand outside and thought about the icy coverlets of Lake Michigan, the tang of cold so palpable that you could see it through the windows, in the violet stillness of an early sky or the welted darkness of midnight. He thought about fishing and carrying plastic tubs of fresh-caught yellow perch and largemouth bass. Playing with a child-his child, their child-out in the snow. Breathing in air that didn’t pop against his throat in an acrid burst of sand.

Lilli never doubted she wanted to do this. He thought if you peeled back a few layers of her skin that you would find cells built up like a periodic table, neatly stacked on top of each other in ascending order of atomic number, organised by element. The chemicals listened to her, winding from the tips of her fingertips, settling themselves neatly into exact weights without a scale (though she always did double check) and when she crossed to the chalkboard to work out a mole here, a sliding scale there, a quantum complexity, the numbers jumped to attention. She had a way with the chalk. Just the thought of her looping writing, the lines and crosses unfurling from her fingers and the press of her hand pulling friction across the rough green of the board made him ache a bit in the open hands of his pelvic bone.

They had similar minds, and similar senses of humour, Lilli and J. He didn’t actually know what the J. stood for, which he supposed he should, but that’s how he introduced himself, ‘Call me J.’, and if anyone else said it it would sound like they were trying to be slick, but with J. it was quiet, and contained, like everything else he did. Even his humour, like Lilli’s, was quiet. A dropped word, a flat sentence, a knowing crinkle at the edge of chapped lips. He wondered if Lilli had told him. When J. had pushed this assignment on him, he had smiled, the cool white of his face not betraying the nerves that Donald was sure were contracting and pulsing under his curved lip, his ridged nose, his equanimous eyes. ‘Good practice, this, Donald,’ how could he still find humour in this moment, the black crack-china sky outside, the scream of the sand, the swaying of this thing, all those many feet above, the test that would decide the fate of everything the fate of him ‘I’m sure you’ll need some expertise in babysitting, soon enough.’

She’d definitely told him, hadn’t she.

He never knew though, with Lilli. Or with J. He was rather prescient; this whole idea was prescient, he had to have had a touch of the oracle to even think of it. His eyes were globular and frosted like a crystal ball, a parma-violet shimmer to them, geode-bright. He had knuckles that pulsed against his skin and the curl of his bryll-creamed brow always reminded Donald of a cresting wave. He didn’t look like he could be part of this world and at the same time looked too part of it, as if he’d snatched all his flesh and cloth from the land around him and sown himself into not quite a man.

He was someone that could do that, stitch the universe how he wanted it, clever fingers puckering and pulling the starry sky into a scarified suit of freckles and too-sharp wrist bones. It was like he could feel the atoms suspended in the air around them, pluck the green nuclei with its orange electrons and silvery magnetic rings and place it between his lips, under his tongue. When he figured out an equation that’s the face he would make, like he was sucking on a particularly good piece of candy, sugar-coated and maybe lemon, maybe one that would sting the sides of your gums a little, that fizzle of electricity between the soft velvet of your inner mouth and your teeth. Maybe he was that sensory, that in tune with the thrums of the universe that he could see through skin. He wondered what the vibrations of Lilli’s insides would look, the pale red of the blood walls and the rosy fists patting against her stomach.

Maybe J. knew before Lilli did. Maybe J.’s eyes snapped open in the dead of the night, when Donald’s hips had met Lilli’s and the silver-pink spangles of her insides cracked open and he watched in the milky gloom as the ground zero glow of them together fused and the splitting cells formed mushroom globes of zygotes and fingernails. Maybe that’s where he crystallised the final format of the equations, in the dark of his own room as in the opposite end of the facility Lilli smoked a cigarette and Donald pulled the blinds down. Maybe he disassembled his own body into the ether and phased through the metal and wood of the corridors, over other sleeping bodies, into the skin of their stomachs and burrowed in amongst the yellow-red flesh. Maybe he tented his fingers as he did when he patrolled the lab, furrowed the narrow between his eyebrows, spoke in numbers with the alien-eyed pink in her belly, let it explain to him how to split and fuse and shatter and grow. Maybe as Lilli grew, and the colours and hum inside her pushed its toes up against the silk of her belly, something in him grew too. Maybe as she swelled with atoms and cells and crosses and eyelashes the same things swelled within him. As she would begin buying clothes and cots, he would be nailing together metal sheets and slotting in plastic tubes to make a baby-bed of his own. And there was Donald, growing nothing. Watching over the things in the cribs. How long was the gestation period of uranium?

The storm, as the proverb would go, was growing worse. There was a slat between the wood of the shack boards he could see out of. He was thankful there was no real window. The fracture he could see through, and the long tendrils of the night cracking through the rims of the door frame, gave him the scope enough. There were none of the desert dust stars whose reflection he had drawn between the freckles on Lilli’s thigh. Just a weird, choking black. Its’ edges looked puckered, pulled tight. The perennial violet smoke that hung like brothel perfume around the spindly arms of desert trees and jewelled thighs of cacti, and the few paint-smears of the facility lights in the distance, always visible from across the open plain; both were swallowed by the swollen clouds that fattened as the time slipped past, their stomachs bloating and bleeding over the moon. Donald felt damp, the cool-hot tang of water that had yet to fall breathed its sweaty fog over his shoulder and down his spine. J’s baby, his charge, swung safely, its slight knocks and metal snores and the stretch of its warning-marked muscles making the night sound soft. He wondered how long it would take for him to see the lightning. He turned another page.

He remembered the first time Lilli had given him a book to read. It was a Conan Doyle, not a Sherlock Holmes but some poky little thing with a bright white cover. He couldn’t even remember the title. He stayed up all night though he had a test the next morning, his reading light hidden under the sheets, fingers pressed to the type as if by proxy he could feel the tips of her touch skimming across his own hands, over the bumps of his knuckles where she had traced the outline of a ‘u’ or the ruts of a ‘k’. They hadn’t so much as brushed hands at this point, so that book felt like the equivalent of her mouth pressed over his palm. He ran tutorial groups (it was the last year of his doctorate, and he didn’t have a thick record of educatory experience, so he thought it would be a bright decision) and she was in the first year of her doctorate. He ignored a lot of the other students. Until he graduated, those swappages of books whose spine had borne the cracks of her quick fingers, whose bent open pages belled out like the phantasmal spread of her hips, whose rounded edges recalled her raised shoulder bone, kept him awake as much as his thesis. He took her to the park the minute that he held the furled paper of his PhD in his hand, and in some jam-lit Boston field she fell back onto the grass with that bleeding coat and two days later he proposed.

She didn’t even hesitate when he got asked to pick up to this mescaline-strung desert. She was used to moving, had her name written on the bottom of her Prague shoes and the bags packed before he even decided whether he wanted to go. They didn’t know anything but that there would be numbers and equations. While he couldn’t sleep for the itchy thought of the sand and the endless questions of what he would be making and what they would smell hear see (the pepper-tang of gas? the bang of rocket testers? the silver spangles of a solution eating its way across a disinfected table?) Lilli hoarded magazines about hot climates and which boots were best for desert surface. The questions that haunted him danced in refractory lights behind her eyes, and she drew aimless repetitive drawings of what she thought they were going to help create in her notebooks. Her favourite was a blobbish mutant. She spent hours shading it in with her green studying pen. She catalogued its lifecycle, until the line boxes of equation paper were filled with growing glowing muscles, and a baby with a wailing mouth like a split, threadbare lime stretched and filled the page with its ghastly scream. Prescient, as always.

The crib whinnied a little bit in the night, and the sudden loudness against its previously quiet chatter startled him, and he dropped the book. Bending down to pick it up, he let himself look at it properly for the first time. Before, he had been refusing to, as if by ignoring it wouldn’t act out as it would if it knew he was giving it attention. The reliefs of the sky outside and the yellow bubble of his reading light made it look almost like waves were caressing the smooth edges of its triangular toes. The cottony glow snuck into the groove of its control hatch, and something in it glittered inside as if under the metal there was a sheet of violet-dusted glass. His fingers itched, and part of him wanted to pull back the coverlet and see. Maybe that was a control blanket? Prevent wandering hands from plunging into the wires and setting off something too soon? They might not just be suspicious, corrupting fingers but the oil-stained digits of clumsy engineers. Having to slide back the sheet of glass would get you in the headspace ready to work with fiddly wires and fuzzy cells that wormed through cloth and fingers and ate up the enzymes that pushed the metal of your heart muscles.

He didn’t know whether there was glass under there or if it was just a trick of the light. He actually had no idea what it would look like at all, under the stretched cover of the metal. He helped manage the chemical content; the engineering side of it all was not his department. They were discouraged (perhaps intimidated would be a better word for it) from speaking about what their own contribution was, banned from trading instructions and ideas. They liked each department to keep their components separate. He wondered how many people knew how the whole worked. He knew J. did. Professor Fermi would too, the strident Italian with forever chestnut skin and luminous eyes, his horseshoe hair bent like a lead cable; he’d come up with the first reaction, so he must have known where all the pieces would fit together. He never knew how those two stood each other. Fermi was funny, whip-smart but manic with hilarity. He still pulled pranks around the office. He remembered the whoosh of ketchup after Fermi had mixed baking soda into the bottle in the canteen, the red drips cooling over the white food benches, dripping off the end of J.’s slight nose. It was a droll moment, a moment that made them all smile, and even J. gave one of his rare, quiet chuckles, but Fermi was always on like that.

Sometimes Donald forgot that beyond his frantic hands and galloping laugh Fermi was one of the smartest people there, that it was a lot of his equations and directions they were studying and reciting, stroking and reverently rewriting, keeping beside their beds, the last thing they read before sleep. He assumed that Fermi dialled himself down when it was just him and J. J. certainly never turned himself up. He wondered who had held the sheath of collated papers and diagrams, proof, first. Who would be the first name people would say after it dropped.

The control hatch was v shaped, triangular doors latched with a few screws that would probably need an industrial tool to split. He hadn’t wanted to touch it, but his hands moved their way over without his permission. The metal and layers of lead were cool to touch. He smoothed it down the side, let his little finger trace the small slats that ran down its side like bars, keeping the thing inside smooth and secure. He brought his hand back up to its belly, drew a few lines with his thumb across the control hatch as if the pad of his finger was an incisor, could give him a glimpse into the dewy cave of pulsing uranium inside even though he knew that would lay well below the skin of it, shrink-wrapped in protective lead organs and fat walls of tin. He laid his hand flat on its convex surface. The belly of it tapered back into a slim waist, pushing out into the aerodynamic fishtail at the top. The jolt of wind periodically filtering in through the hole-pocked wood of the shack made it bump and sway a little under his palm, the bubble of its movements pushing it gently back and forth, kicking against him.

He thought of Lilli. She wouldn’t feel it yet, like this, would she? He certainly wouldn’t be able to feel it from the outside, yet. That came later. (He was quietly happy about that. He thought he would need some time to deal with it. Some squeamish little boy in him recoiled with a fascinated excitement at the thought of a being pushing its distorted little foot against Lilli’s stomach and stretching the skin like rubber. He was also terribly aware that that point, the point of external vision, would be the point of reality. He would know and would have to accept that this was coming. he was just happy about her news, at the minute, but he was cognisant of the magnitude of change that would take place once that foot was visible, and his hands could feel it through the skin).

But he wondered if she could. He wouldn’t blame her if she hadn’t told him yet. It must be an odd feeling. Part of you and separate too. He might want to have a few days, if it was him, feeling that for himself, nobody knowing, nobody around. He wondered if J. had stood like this, hand on his surrogate stomach, feeling the wriggles and movements of the warmth of growth below. He felt for a moment rude, like he had placed his hand on a mother’s stomach without asking. He removed his palm, shuffled to his corner, eyes back on Dorothy Parker. The silver glint of the thing twinkled, a bright glassy shard that warmed a baby with the power to tear his face loose from its muscular stitches. Dah-dah, dah-dah, dah-dah.

It might have been the smoke of the cloud outside, but the small slat seemed to be growing bigger, its edges jagged with splintery wood. He swallowed the thick air and pushed his face to it. The rough rim irritated his five o’clock shadow—they hadn’t had a ship of razors in a week, and it was starting to play out even on Donald’s blonde chin, while Fermi was attempting to grow an impressive Groucho Marxian curl to panhandle for laughs—but the view was worth it. Far below him the sand retched up into clawed fingers, scratching at the sky. Far above, something screamed, a blackened lump fell, landing somewhere under the tower. He could see the beam of jeep lights curving close around the tower, frosted and smudged, before flickering back towards the direction of the facility. A slit of lightning peeled back the darkness for a second, a fissure of mercury running down between the split halves of the blurred sky.

He shifted back from the window, and he felt his windpipe clench in a panic for a second. He suddenly seemed very high up. The lightning repeated its scar across his eyes in a ghostly chromatic imprint. It was too close. The thing moaned in the wind, the long high beginnings of a cry. He was suddenly aware that here, in this satellite dish of a shed, teetering on this metallic tower, the electricity in the air probably had him in its sight. The forks were dancing around him like a mating bird, its flashes the high whistles of arousal. If it grabbed him by the waist, made the final move, he wouldn’t have time to recognise that he was gone. None of them would. The little difference between life and death, what he used to think was a gulf wider than New Mexico, wasn’t even a footstep. This baby, swinging there with its cataclysmic heart, would ensure that it would be less than a second. He leant back against the seat. He suddenly didn’t want to look at it anymore. He imagined its mouth red and slick with saliva, ruddy with the beginnings of uranium teeth. This made him wince, and he turned his face further into the wood.

He thought he might try get some sleep, but the thing rocked and warbled behind his eyes too. The closeness of the shack felt hot and delirious, and he hadn’t been to bed in so long. His back hurt where it pressed too harshly against the wall, irritating the watermarks Lilli long left behind. She hadn’t cut her nails for a few days when she had found out their news, and he was fresh from a shower when she gripped him in a vice-hug, the points of her fingers shredding his damp skin. He itched and pawed at his lab coat, where it stuck wetly to his front. A feverish thought told him he had been vomited on, and still with his eyes closed he wrestled to throw his shirt off. There was something glowing, eating at his chest. He was scratching at it, and it burned further. It was chunked with hocks of yellow-green, barium-bright pulp. Nuclear sick-up. The lightning was too loud, and the screams of desert animals felt like they were in the room. The yowl vibrated in his neck muscles and the soles of his feet, and his chest was still hurting. It sounded like a siren. His skin fell apart into milky strips, and the gooey lumps of his arteries fizzled in the air. He was only smearing it around now, and his hand fell from the mess uselessly, tired and weak. He could see flashes of bleached-white rib bone, and the hint of a red thud beneath it.

The thing was crying again. It was louder now, and it combined with the storm screech and scratch of animals and sand way down below to cause echoes under his skull. Lilli rolled over from her perch next to him on the wooden shelf. Her hand was soft on his forearm, and her fingers gently rolled his skin back and forth over his wrist bone. Her fingers glowed, blurring from black to purple to silver to green as different patches of the sky outside drifted in and out of prominence. Her belly was flat, but not the flat it used to be. Jelly-like, as if something had been there and now it wasn’t.

‘Donald,’ skin moving back and forth, back and forth, back and forth. ‘Will you get her?’

He pushed himself off the wooden shelf. She turned back, the curve of that lovely bleeding shoulder-bone black and purple and silver and green. He padded over, the threads of chest skin waving gently in the night air of the shed. The hatch of the bomb was open. Interestedly, he looked into the open space beneath it. There was a baby. Its mouth was open, and it was sitting up weakly on its pudding thighs. A frosted glass blanket swamped around its little belly. Its mouth was stretched open, and its curls were damp stuck to its forehead. The sound that screamed out was artificial, siren-like. It sounded mechanical, and the grinding of its nubby teeth held the clink of metal. Its muscles were green against its skin.

He reached in. It was hot. He could hear Lilli’s soft snores from the other side of the room. Once it was in his arms it stopped crying. He looked at it. It looked at him. Its eyes were the same luminosity of J’s. It placed a fat palm on his cheek. His brain registered with detachment that his face was smoking underneath its hand, and confetti flutters of teeth and skin were stripping away and floating down to hang around his jaw. It papped its feet against his chest. Its eyebrows, he noticed, were thick and black, like J’s. Even more strangely, though he hadn’t seen it before, with some interest he lifted a soft finger to trace the luxurious moustache that had curled out from the baby’s nose. You don’t look like me, he thought, without concern. It smiled. When its mouth opened a wooden coo echoed out.

The silver white of a lightning fork burst, shattering the black of the shed, and Donald found himself with sticky eyes, standing over the bomb. His arms were outstretched. His cheek burned. The panel was closed. He turned slowly, and the wooden shelf where he had been sitting and Lilli sleeping was empty. He stumbled back over. The light broke over Dorothy Parker’s nose. It was nearly dawn, the starry fingers of the sky pulling down satiny strips of split-peach and lilac over their toes. He could have sworn that mere moments before it had been midnight and his heart had been colt-beating in tune to the thrum of the lightning. It wouldn’t be long before J. would scale the ladder up to the shed, would check that everything was okay, then they would do whatever they were going to do to get the thing down and ready, and then the armoured cars would take J and Fermi and him and the others and he would hold Lilli’s hand from behind lead-plated plexiglass as it would tear its way into the world through a seam of sky, red and ugly and screaming.

It seemed bigger, now, like the sweltering wetness of the night had left it content and fully gestated. Maybe it needed the evening of sucking off Donald’s fear and love, the last droplets of terrified colostrum, before it was ready. Maybe the whole storm was the thing’s making. Braxton Hicks vibrations, preparing the muscles of the air for its entrance. The coo echoed around Donald’s head. He dragged a hand across his cheek, which still ached, and found it came away sweaty and wet with blood. He bent down to look at his reflection in the silver surface of the bomb. There was a small scratch near his cheekbone, which he must have got pushing his face up to the window.

The bench was cool, and slightly damp. The swelling clouds must have broken at some point. The sand under the slat looked soupy and thick. He could see the facility now, the glint of the gates in the burgeoning sun. There was a car stopped at the checkpoint, about to leave. It must be coming for him. He thought he should look back, make sure it was still sleeping unmeddled with, that all was right in the crib. The high, sweet coo clanged off his amygdala, and the sheer pain of it stopped him. He started back down.

The climb was long and the sweat on his palms and the damp undersides of his boots made it longer. He did not stop thinking of that thing, in its glass coverlets. The fuse pacifier curling out of its sleeping lips.

J. was waiting at the bottom for him. He was pristine, the white of his coat shredded straight from the skin of the sun. His eyes were green today. They looked juiced and full, shiny as gastric acid. The cleanness of him, untouched by desert dust and the night dirt that had wormed its way into the cracks under Donald’s eyes, roiled Donald’s stomach. The soldiers that were with him hupped their way up to the shed to secure it or lower it or whatever they were told to do. Fermi was there, tap-tap-tapping on one of the thick legs of the tower.

‘Did he sleep through the night?’ he grinned, and the twitch and bristle of his Groucho moustache wastoo familiar. ‘No waking up for a feed?’

Donald vomited. It sputtered into violent bright shards around his feet. It was the same strontium red of Lilli’s coat. Stars spangled to and fro behind his eyelids, and fragments of the sand beneath his feet vibrated, pulled at his toes through the hard leather of his shoes. J. put his hand on his shoulder. He looked resigned. He knew what he had brought into the world, and like a true mother, loved it despite its ugliness.

Donald wiped his mouth, watched the initial descent of the crib out of the shed and down the tower. The soldiers’ hands were gentle, rocking it to keep it sleeping as they lowered it from the shed. He thought of the swell of Lilli’s stomach.

He suddenly felt like he had been looking after the wrong child.

The coo echoed, wooden and loud, in his head.