It won’t come as an earth-shattering surprise to those that have already seen it, but after watching Greta Gerwig’s 2017 directorial debut Lady Bird, I immediately wanted to call my Mum and thank her for everything she’s done for me. Described by Peter Bradshaw as ‘a love letter to teenagers and their mothers,’ Gerwig expertly marks a daughter’s trajectory from solipsism to gratefulness; a mother’s journey from pained protectiveness to hesitant understanding.

The character of Christine ‘Lady Bird’ McPherson, played by Saoirse Ronan, peppers the plot with distinctive and nuanced acts of rebellion that traverse different levels of severity. The only character with hair dyed a bright and thus (in a close-knit suburb of Sacramento) unorthodox colour; declaring defiantly that she will apply for art colleges in big bad New York City, rather than the universally assumed Sacramento City College, Lady Bird is a character that convinces herself she is unencumbered by the insecurities surrounding self-image and identity that haunt teenagers whilst coming-of-age.

Even our protagonist’s name, ‘Lady Bird’ presents the audience with an epithet that is both outwardly confident and purposefully ‘other.’ When asked for her ‘given name’ by a teacher in her Catholic school, Lady Bird responds with the obstinately iconic, ‘that is my given name; it was given to me, by myself.’ Not only does this scene epitomise Lady Bird’s search and subsequent declaration of personal autonomy, but this process also seems to strip Marion (Lady Bird’s mother, played expertly by Laurie Metcalf) of that authority. The naming of a child, although not an experience I am familiar with myself, should be both an intimate and bond-forming experience, a symbol of family, a gift to mothers who have birthed and pledged their all in raising their children. In this, the audience glimpses the distance wedged between the two, and thus the film is seen to acknowledge and lay bare the complexity of mother-daughter love.

Although there are scenes where a unique tenderness between daughter and mother is displayed- crying and driving, listening to an audiobook or shopping for a prom dress in the local thrift store- these moments are incessantly undercut by torrents of emotion, usually anger by both parties. As both characters are desperately abrasive, they are also strikingly similar, paying lip service to the phrase, ‘like mother, like daughter.’ The notion that the maternal relationship is also one of friendship is nothing new, but this part of Lady Bird and Marion’s relationship is particularly strained as Gerwig exhibits screaming matches and short but witty gripings. In a particular argument revolving around money, Lady Bird (cleverly but immaturely) asks for a figure that she has cost the family, of which she pledges to repay after college. Yet such comedic temerity is met with Marion’s cutting retort, ‘I doubt you’ll ever have a good enough job.’ It is through these particular exchanges- unsurprising given that Gerwig is especially talented at composing dialogue- that Lady Bird’s questioning, ‘you love me, but do you like me?’ is both thought-provoking, and somewhat difficult to swallow.

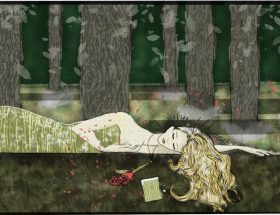

Returning to the scene in which the two are driving, listening to the emotional audiobook, the sequence soon begins to unravel as conversation turns (as it so often does in maternal relationships) to the child’s future. After arguing that the family barely have the funds to send Lady Bird to the local community college, let alone send her to New York City (a place that represents somewhat of a monster to Marion in her protective, maternal duties), the former flings herself from the moving vehicle, where Gerwig cuts to the two in the hospital as the adolescent’s arm is broken and in a cast. This display represents cinematically a teenage daughter’s longing to escape so-called ‘small-town life,’ where the cast is the iron-clad embrace of a mother, fearful of abandonment and the much-theorised ‘empty nest’ syndrome. Moreover, Lady Bird’s purposeful self-harm irrefutably scuppers Marion’s life-long objective of keeping her daughter safe; and so her aim is dissolved in front of her bulging, horrified eyes.

Gerwig’s proficiency for detailing never fails to impress, and a close-up of Lady Bird’s cast reading ‘f**k you mom’ serves to solidify this act of punishment sustained by Marion. Whilst I mentioned previously that Lady Bird believes she is unburdened by the worries and anxieties of her generation, she is seen to present herself in direct opposition to her mother, whose (at times) vitriolic comebacks exhibit her own insecurities in public display. Frequently chastising Lady Bird, Marion’s money troubles- which often translate into class anxiety- and fear as she seemingly hurtles towards an ‘empty nest,’ allow audience members (especially those such as myself who have filled the role of daughter but not yet mother) gain valuable insight into the tribulations of mothering an adolescent daughter.

Perhaps the most interesting facet of this film is its semi-autobiographical nature. Countless critics have noted that Gerwig, much like Lady Bird, grew up in Sacramento, went to Catholic high school and left for New York for college. Although it can only be posited that the film has certain (loose) cognates of Gerwig’s own life, it is nevertheless interesting to note that it may be that the dazzling emotional grace displayed within the film is due to Gerwig’s own personal experiences. Haven’t we all had that awful argument with our guardians over leaving the house in whatever, or spending time with whatshisname? The sandpaper effect of mothering a daughter – and daughtering a mother, if such a phrase were to be grammatically correct- is represented expertly through this cinematic masterpiece, where what the audience is left with is a polished, clarified understanding of each other’s love.

This was a film to savour, and one that is almost universally identifiable. It is difficult to fight for independence as an adolescent when strictly speaking, at least to the adults, you are still a child. It is equally arduous to strike a balance between love, respect, protection, freedom, confinement, resentment and frustration in the infinitely complex relationship between mother and daughter.

It is a love, as Gerwig portrays, that cannot be bound by expectation nor longing. It is simply unconditional, omnipresent, sometimes silent, and sometimes deafeningly loud. It is easy to forget, hard to miss and devastating to lose.

art by Quinn Fagersten