“ Article 1. All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.

They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.”

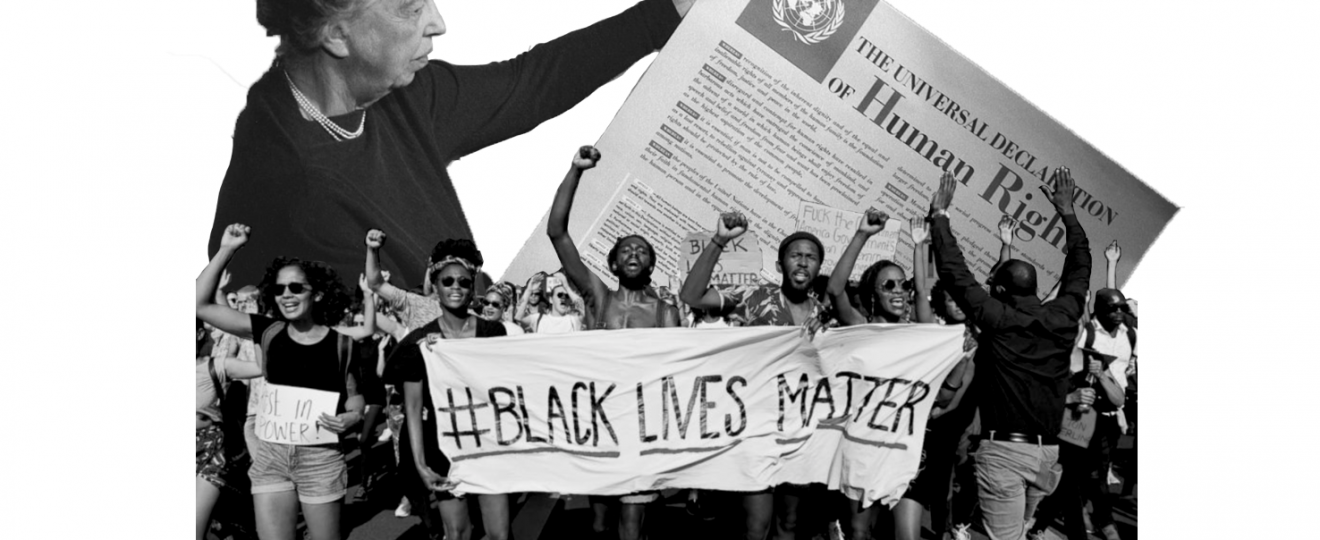

In 1948, the US signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, swearing to protect the equality and freedom of all human beings with one hand, while continuing to choke the liberties and dignity of the African American population with the weight of the Jim Crow laws (and all their overarching consequences) on the other. To believe that this country pledged to protect equality in a way that truly acknowledged over a hundred years of race inequality and racial injustice, would be naïve. To take at face value the word of a state that claimed to believe an ideal while actively crushing it, would be to fail to grasp what Article 1 of the Declaration sought to express.

At their very core, regardless of whether you believe they stem from a natural right or from some politically constructed principle, human rights are based on a notion of shared humanity. On the idea that not only do we all have a conscience and the capacity to reason, but that we can feel pain and affection, that we have a common emotional set with which we connect to one another. It is in the recognition of this principle of shared humanity where the notions of equality, freedom in all its different forms, of the rights that should protect us, are rooted. On the fact that we are human beings– nothing more, nothing less. This is what Article 1 comprises, and what the United States of America, with its Constitution under its arm, has structurally and systematically failed to understand.

The murder of George Floyd under the knee of police officer Derek Chauvin is the latest American punch at the idea of shared humanity. I don’t think words suffice to describe the horror of the event, and I don’t think it is my place to explain the pain that it has caused. So I won’t. But I believe the image of the event, even for those of us who have decided not to watch the video, is a tragic, albeit accurate, representation of how whiteness is built on the denial of common humanity. Race is inarguably biologically determined, but the racial identities to which issues of racism can be traced back to have been consciously constructed throughout the course of history, consistently playing on the blatantly false and unacceptable belief that, while the white individual is fully human, the black individual isn’t. Whiteness has claimed ownership over the concept of humanity and the rights that come along with it, forcing onto black individuals the ignorant and hateful weight of who they are, what they feel, how they behave. The weight of a narrow and violently bigoted definition of what it means to be black according to whiteness. The white obsession with controlling what it means to be black (because, obviously, there has to be a definition) has been suffocating black people for centuries. In pressing his knee against Floyd’s neck, in murdering Floyd in broad daylight, Chauvin continued this process: he assumed who Floyd was and how he acted, based on Floyd being black; he felt comfortable ignoring the physical pain he was exerting, based on Floyd being black; he was not scared to do so in the middle of a street full of people, based on Floyd being black. He acted according to a mentality that has been in the making for centuries.

The dehumanization of black people has evolved subtly, adapting itself to the progress in their rights, but following a consistent internal logic. The most blatant denial of their humanity has been their equation to animals, to beings whose pain is not only to be ignored, but also exploited to control them, who can be legally transported against their will, separated from their families, and forced to work under the authority of the white man. The equation, effectively, to beings who are less– less worthy, less important, less human. After the abolishment of slavery (which, let’s not forget, was mainly driven by Northern industrial economic interests, rather than by deep-rooted concerns for the black population), the comparison of black people to animals began to shift, but the emotional, behavioral, and even aesthetic assumptions which underpinned it remain to this day. The white man can be anything: he can love his family and his neighbor, he can work for his country and fight for its honor, he can be intelligent and funny, attractive and brave, strong and understanding. He enjoys the idea of humanity in its full versatility, for he is not defined by the white men who are otherwise. Whiteness has not only denied black people this privilege, but has treated it as if it weren’t such. In its monopoly over fully-fledged humanity, it has decided that, like animals to be caged, all black people are aggressive, violent threats to society, all black people are incapable of loving in the way a white person can love, all black people are incapable of embodying the beauty a white person can. Whiteness’ denial of black humanity has asserted that, while the white man, in his condition of being a full human being, can be anything, the black man cannot– what would be the exception to whiteness, has been presented as the rule to blackness.

This dehumanization is everywhere. In the media, it takes the shape of the angry black woman stereotype, of the problematic gangs which are always made up of black (or Latino) kids, of the father who either beats his wife up or is in jail or spends his days drinking. We see it in these and so many other two-dimensional stereotypes, which feed us the images and narratives we have been taught to both accept and expect; but also in the form of black but not really black characters, whose level of education, behavior and emotions are portrayed as being completely different from what black people normally are. In the arts, it presents itself as the lack of acknowledgement to the value, importance and even authorship or origin of works, techniques and customs created by black people. In the news media, we swallow it in the form of derogatory terms, mugshots that don’t even tell us half of the story, and out-of-context statistics that serve the role of supporting the fallacy that criminal problems in the US are the sole and direct responsibility of black people (and Latino minorities). We see it in the structure of the whole system, from access to education, to a judiciary designed to punish more severely certain actions over others (such as the use of crack over cocaine), supported by a law enforcement trained to target and surveille some communities over others. (This is, in fact, a historically rooted practice– in southern states, police bodies evolved from slave patrols; in the north, they evolved as a way to control a dangerous underclass, African-Americans, Native Americans and the poor). In police brutality. In the murder of George Floyd.

In its denial of the principle of shared humanity, white systems of power have construed black individuals as being identical copies of one same model, as being disposable. Declaring disposability implies declaring a lack of importance. In the same way the death of a slave was treated as an inconvenience to the white oppressor, the continued murder of black people (who are two-and-a-half times as likely as white Americans to be killed in these circumstances) by members of law enforcement, has been treated by political structures and by a section of the white population as nothing but temporary disruptions to a normal state of affairs. (A normal state of affairs which is heavily defined by the roots and overarching consequences of the discrimination against black people). Whiteness and white power structures have employed this false disposability as a tool in the continuation of the reality from which white people benefit, as a mechanism to avoid questioning why a supposedly democratic and free state allows for the continued murdering of a sector of its population. As a bigoted fallacy that perpetuates a culture of lack of accountability of those responsible, because it suggests that the problem does not matter.

Black lives matter. Black lives are not disposable. They matter not simply based on attributes that we see as positive, but because they are lives, and no life, including black lives, is disposable. Headlines have been detailing how Floyd was an athlete, a father, a beautiful spirit, reclaiming the narrative away from police officers’ statements that he was drugged and resisting, clearing his image from the claims that implied that he was just a thug. And, as important as this is, we can’t forget that the need to humanize Floyd, to humanize victims of police brutality like Tamir Rice or Breonna Taylor, is rooted in the fact that their fully-fledged humanity has to be proven, and can only be proven, in the eyes of white systems of power, by showing that its content does not coincide with what whiteness has defined as blackness. Before, during, and years after signing the Declaration of Human Rights, the US failed and fails to grasp it. Article 1 states that all human beings are free and equal in dignity and rights; it states that, from the second a person is born, she deserves nothing less than to be treated accordingly. It quite clearly implies that her life, no matter who she is, no matter what she has done, should never be taken away by prejudiced, bigoted and hateful actions. It states that, in the same way that white lives don’t have to be justified when they’re brutally taken away, black lives don’t have to be either.

Black lives are not disposable. Their dehumanization most certainly is.