‘If it takes a village to raise a child, it takes a village to abuse one’-Stanley Tucci as lawyer Mitch Garabedian in Spotlight (Tom McCarthy, 2015).

2015’s Spotlight is a powerful film. I am not one qualified to discuss composition, lighting, and angles but, in its narrative, it is an undeniable force. The story of four journalists and two editors from the Boston Globe in their quest to unravel and demonstrate decades of historic sexual abuse within the Catholic Church, and the institutional wilful negligence and concealment that facilitated it, Spotlight details a slow realisation of the extent of the problem, the uncovering of the awareness and lack-of-action on behalf of the Church’s internal governments, and the eventual exposure. It also shows the psychological trauma of both the abuse victims, and those who fight on their behalf, as they rail against a faceless, economically, and socially sovereign institution. They meet dead ends, silence, cover ups and ignorance, all the while with the ticking awareness that the longer the Church stalls and prevents them, the longer the instances of abuse can happen unchecked, unprevented. The longer it takes for them to be noticed, the more children are hurt. They are, unconsciously and consciously, terrified of failure, as failure puts them in the same position as the callous Bishops and leaders they condemn; the position of knowing an evil is occurring, and not preventing it. Or as Mark Ruffalo, acting as journalist Michael Rezendes, screams in a particularly moving sequence ‘They knew! They knew, and they let it happen!’. Behind his anger, disgust, and disbelief at the Church’s lack of action, its cold tolerance, is the fear that they lapse into the same silence. Their story will go unheard, and they will live, knowing what is happening, and doing nothing.

It seems odd to start a piece about sexual assault on a university campus with a discussion of a film made five years ago, about a newspaper investigation undertaken fifteen years before that, in a different city, in a different country, facing an entirely different age group at an entirely different institution, but I want to begin by taking Mr. Garabedian’s quote, and just tweaking it slightly. If it takes a town to educate a person, it takes a town to abuse one.

On the second of July, 2020, a blue-coloured page bloomed into existence in the field of Instagram poppies. Its author was faceless. Its logo, and its mission, stark. Its name; @standrewssurvivors.

The concept is not unique amongst universities, or comprehensive/high school campuses (though, its commonality makes for a disturbing thought). A place for survivors of sexual assault to come forward, anonymously, and submit their experiences. To rid themselves of the burden of carrying their stories alone, their identities made safe by the faceless screen. To point out the failings of the institution of St. Andrews itself when faced with their allegations, to illuminate the clear holes in the way our university addresses and responds to traumatised and hurting students. To have a sympathetic ear in the comments, perhaps unfound amongst offline compatriots (it’s always easier to be nice online, when everyone’s watching, you don’t know the victim or perpetrator, and you get points for how liberal and pro-victim you are), an ear that replies to their submission with an I believe you, I support you, and I am sorry you had to go through this. Maybe in the hope that amongst the posts of their fellow survivors, their story will make a change. A change to protect others.

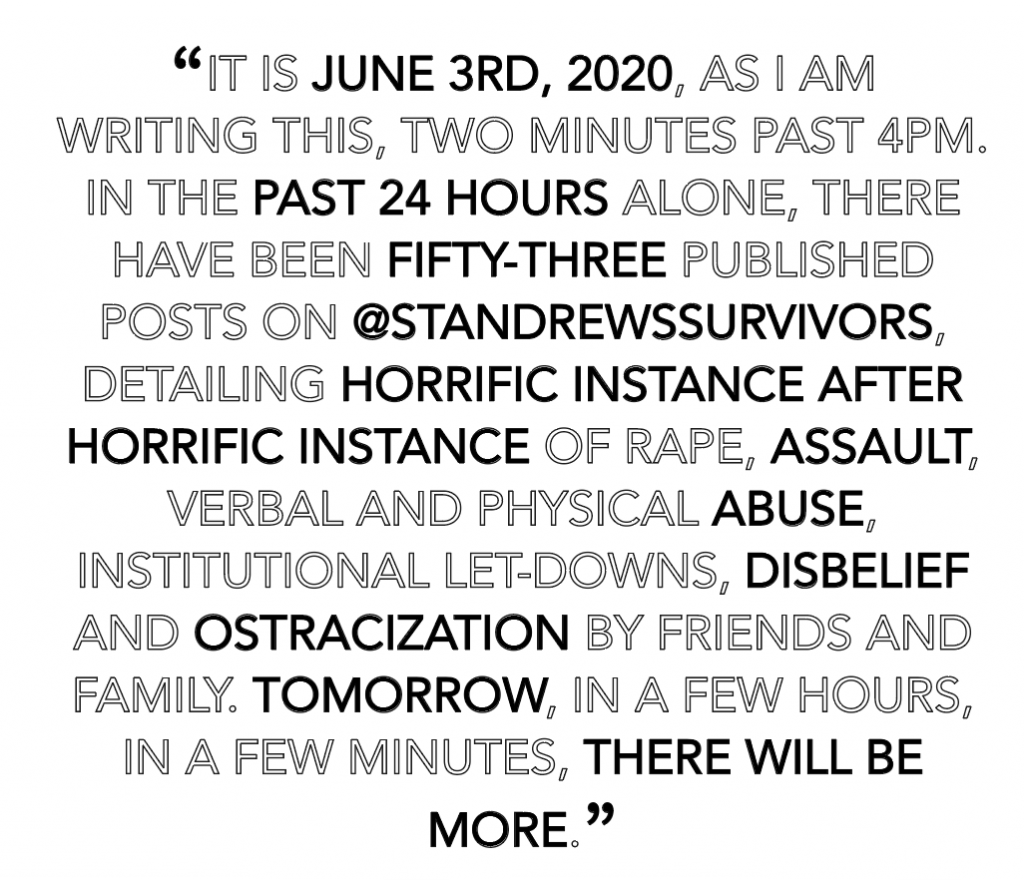

It is June 3rd, 2020, as I am writing this, two minutes past 4pm. In the past 24 hours alone, there have been fifty-three published posts on @standrewssurvivors, detailing horrific instance after horrific instance of rape, assault, verbal and physical abuse, institutional let-downs, disbelief and ostracization by friends and family. Tomorrow, in a few hours, in a few minutes, there will be more.

The most surprising thing about this is that we are pretending that we are shocked.

Because I am not shocked, and realistically, neither are you.

We knew, as Michael Rezendes said, we knew and we did nothing. The university, by and large, did nothing. Perhaps we didn’t know the victims, perhaps we didn’t know the perpetrators, but we all knew it was happening. Perhaps you can see why I started this with a discussion of Spotlight. Perhaps the parallels between a faceless institution that ignores abuse, a public that turned their faces from it, and a de facto culture of silence and shame seem clearer, now.

I have spent three years in St. Andrews, and I have collected half-stories about what not to do, who to avoid, where to drink and where not to, what societies are famous for their lack of respect for consent. I have collected stories of friends being spiked; I have collected stories about the university’s response being largely are you sure you want to make this claim? Of their assurances that these incidents are taken very seriously, but nothing will ever happen to prevent it happening again or really ever punish the perpetrator at all. I have collected these stories and worn them bright, rage-shiny pins on my jacket that I pull out at home to condemn as awful in front of my parents. It is awful, that even in a town ‘as safe’ as St. Andrews, that I have to walk with my keys in my fingers, and if it is particularly dark call my mum my dad my boyfriend anyone, just to show that I am not alone. It is awful, that the university responds to traumatic events with a he-said she-said defence that usually ends up with a perpetrator free and the survivor forced to cope with the multitudinous trauma that remains post-assault. It is awful that the drinks at the union regularly get spiked, it is awful to see the bouncers laugh when a woman is drunk and a man handles her out of the union, it is awful that though all of us seem to know at least one sexual assault that has happened to us or someone we know over our four years at St. Andrews nobody ever seems to see justice, it is awful that in first year I knew a person who attended a party where someone openly bragged about having a sexual assault case against him by his ex-girlfriend, which he knew he was going to win. It is awful, it is awful, it is awful.

I have never done anything with this knowledge. Some have-like Phil Saviano and Mitch Garabedian, they have prompted GotConsent workshops and tried to make public the university responses, they have tried to tell their friends and raise awareness of known on-campus predators. But the majority of us? We have done nothing. We have known and done nothing. If you are in a society, have you pressured its leaders to include mandatory GotConsent training? Have you pressured its leaders to place a no-tolerance position on members behaving inappropriately? Have you pressured for lecturers and tutors, for student services, to receive appropriate sexual assault training? Have you talked to your friends about doing something to address the culture of sexual assault that permeates the university, or have you just accepted it as given? If you have heard about assault and inappropriate behaviour by known groups, have you petitioned the university to review their affiliation? As soon as the Conservative and the Anime societies (what a venn diagram that would be) committed fraud and electoral malpractice, the union received many (justified) complaints, and their affiliations were revoked. Other societies and social groups known throughout campus for being particularly predatory, all mentioned at least once in the survivor stories, have not received the same treatment. I had heard, through word of mouth, that these groups, and others, were ‘dodgy’. Do not go alone to their parties. Check your drinks. Bring your friends. I am betting you did, too. I am betting that you, like me, did nothing.

It is awful, it is awful, it is awful. It is an awful open secret.

Not merely within these societies but within the town as a whole. We are, essentially, three streets. How many rapists have you brushed past, on the daily? How many of them will go on to hold positions of power? St. Andrews is a university with students that do possess strong economic and social connections and do frequently go onto do big things. How many of those were rapists, were predators, and how many of them got away with it because none of us said anything?

We knew, and we did nothing.

Britain, and St. Andrews, tends to look over America with a superior gaze on many social issues. Most recently, this has been the case with the Black Lives Matter movement, where many of us believe that Britain is excused, above institutional racism (conveniently forgetting who played a part as one of the key founders of the Atlantic slave trade). We do the same with the culture of sexual assault on educational campuses. We look at the Steubenvilles, we look at the Brock Turners, the Daisy Colemans, and we see the way campus rape victims are treated by judges who let their abusers go off with a slap on the wrist and no punishment to avoid endangering their star swimming careers, and we tut tut tut. We don’t do that, here. We see justice, here. The issue is, we have few massive, international-attention garnering campus rape cases here because at least in America some of them actually get to trial. Here, the majority of assaults seem to die off with a are you sure you want to complain? Are you sure that he’s the perpetrator? That’s so out of character for him* in brightly lit offices that makes you think, oh, there’s no point, or maybe as a result of a culture that called the 19-year-old student who accused footballer Ched Evans of raping her while she was intoxicated a slut and a liar. Awful, awful, awful.

The truth of the matter is, like the racism that pervades our society, we are aware of the sexual assault that makes up the rotten core of the St. Andrews experience. I heard about the girl who got punched in Ma Bells-I wasn’t there, but we all knew about it. We all knew that this happened. We knew, Rezendes, we knew, and we did nothing.

But the genius behind the brilliant, empathetic, person who created @standrewssurivors, is not only that they gave victims a safe space among a town and an institution that seemed coldly tolerant and ignorant of their pain, but like the Boston Globe’s exposure of the Catholic Church, they held up this awful, open secret to the light. Like some of the people of Boston, among who the abuse conducted by the Catholic Church was an open secret from which they turned away, the sexual abuse currents that whirl nefariously under the silver lights of 601 and the bright glow of the Vic were acknowledged and roundly ignored, even by those of us who discussed them. They were ignored in that nothing was done. We knew about a few cases, one or two. Not enough to make a fuss about. @standrewssurvivors has made it rather impossible to keep ignoring. It is there, it is happening. We cannot ignore 53 accounts. Squirming, embarrassed, blinking from the cold brightness @standrewssurvivors has thrust upon us, we must take bold steps to make it better. We have no other option. We cannot feign ignorance when they have spelt it out for us. Before, we knew but we didn’t know. Now, we know. Wholly. Unchangingly. We can see the consequences of this already: the six comments under the latest Instagram post of a society mentioned over ten times in survivor stories all challenge for a response to the allegations levied against them. The numerous, thoughtful replies to @standrewssurvivors questions on how to improve the experience of victims in the university, and to prevent more abuse from occurring. The people taking the time to comment I love you, I believe you, I’m sorry under each Instagram post. The people sharing, and discussing, and the survivors who are coming forward. It will not be long before a petition is started for the investigation of the groups being accused. It will not be long before the university is forced to email.

It is rare that an awful, open secret is held up to the light in a way that prompts change as @standrewssurvivors has done. It is rare that we are forced to confront our own failings, and it is rare that we are forced to do something about it. That time is now. We owe it, to all the victims that have shared their stories on Instagram, and all that haven’t, to enact the steps that I elucidated earlier in the article, and more. Perhaps, @standrewssurvivors will provide the cataclysmic proof that we have failed to prompt us to take another course, one that provokes more change than the acceptance and silence we have undertaken until now.

Perhaps, this time, we will do better.

Perhaps, this time, we will be the reporters from the Boston Globe. Perhaps, this time, we can say, we knew, and we did something.

[*a direct quote from a survivor account on @standrewssurviors.]

BRIZO Magazine acknowledges that some may disagree with the premise that sharing one’s own experiences can be part of a healing and cathartic process. However, since the process of submissions is up to the individual’s own discretion and, since some of the stories shared have made reference to the fact that the page has been helpful to the victim on a personal level, we believe there is a case to be made with regards to this positive aspect of the platform.