Yes I’m Iranian, I say. I’m mixed, I say. I’m actually three quarters Iranian, I say. The other part is English, I say. No, my parents were both born in the UK, I say. No, I don’t speak Persian (Farsi), I say. Yes, I do eat Persian food, I say. No, I’ve never been to Iran, I say. Yes, I would love to go one day, I say.

Then I wonder what all those questions, and the straightforward answers I respond with, tells someone about me. It doesn’t really say very much, I don’t think. I hardly understand my connection with Iran, or my family’s connection with Iran, so how could an acquaintance or a friend have any kind of idea based on a few blunt questions and facts.

Both my parents were born in England. They went to school in the UK, they studied at Newcastle University (my hometown) and they have never lived outside of this country. I am, of course, my parents’ daughter. My relationship to the country three of my grandparents were born in is completely in the abstract.

My Iranian grandparents all moved to England before they were married, had kids, and settled down. They also all moved here before the Iranian Revolution. They created lives and families in this country. Then they took their new, Westernised families on trips to Iran to see their family and to see their home. Before 1979, of course.

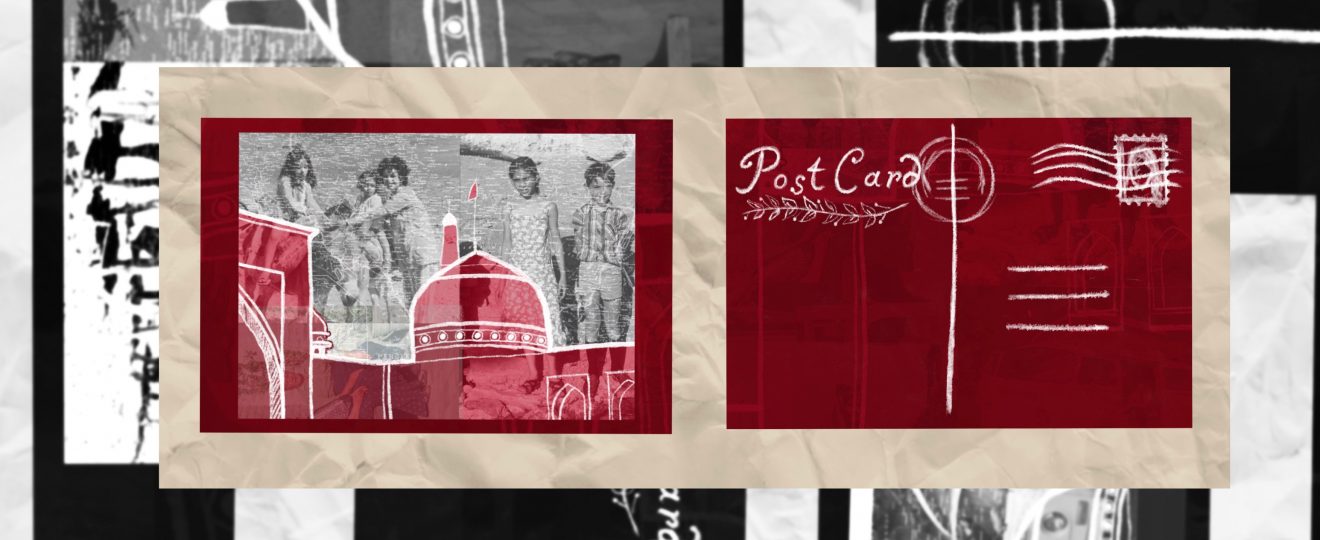

My father, with his quiet, Mancunian (white) father and his beautiful, sociable, Persian mother, sandwiched between his two sisters, travelled to Iran when he was a boy. The family caught a train almost the entire way from England to Tehran. This extended family holiday was captured on camera by my grandfather’s photography – beautiful film photos showing the moment that the Western family was welcomed into Iran by the Iranian family. Granny’s family. My father’s family. So, really, my family. A photograph of my aunt in traditional Iranian clothes, clothes I have never seen anyone I’m related to wear. My dad and his sisters smiling, tan from the Persian sun, stood in front of a fountain, a temple, a mountain, a garden.

My mother visited Iran too. When she was ten years old, a matter of months before the Iranian Revolution. My grandfather was a visiting professor in the south of Iran. My grandmother had lived in the UK since she was a child, sent to boarding school with her sister. My grandpa was a doctor and a lecturer, and he had been worn down by the racism and prejudices of the country he had moved to. But they only stayed for one month.

After the revolution my grandfather’s family home was burned down by revolutionaries, his family’s lands seized by the government. They were not an Islamic family, and Iran was an Islamic country. The revolution officialised it.

My family weren’t refugees when they left Iran. Each one of them left because they were privileged enough to. But had they stayed a while longer, they may well have fled as refugees. None of us can visit Iran. All my aunts and uncle have only visited briefly in their childhood, and none of the grandchildren have gone. Iran as a country, as a familial home, is cut off from us. It is no longer a possibility.

When I explain my genealogy, my heritage, my ethnicity, to people, I find myself questioning the truth of what I am saying. Yes, my grandparents were born in Iran, speak Farsi, cook Persian food and moved to the UK to have a family and a career and a different life than the one had by their parents. Yes, my skin is a bit darker, my hair a bit thicker, my nose a little larger than the Western ideal. Yes, I am Iranian, if you cut me open and look a bit deeper. But I don’t understand how I am Iranian, really.

Am I really more Iranian than the people at my university who have spent four years studying Farsi, or Middle Eastern history? Am I more Iranian than every white British mother who has bought a Persian cookbook in the past few years and has attempted to create a bastardised Khoresh Fesenjan? We have more than a few Persian carpets, but they sell those at John Lewis.

Do a few family photos from a holiday 50 years ago make me Iranian? I wrote a paper on the Iranian Revolution when I was 18, does that help? I try to cook (no doubt inauthentic, Westernised) Persian food for my family and friends, but it doesn’t come naturally. We used to frequent a Persian restaurant in town before it was trendy, when almost everyone in the restaurant was Persian too. I think I felt at home there. I certainly felt proud there.

I come back to my grandparents each time I think about this. What else do I have, really? They are a piece of Iran that I was lucky enough to have, and still have. They are my only connection, besides a few relics of a lost past.

Immigrants, and children of immigrants. And grandchildren of immigrants. First, second and third generation. When do we stop being considered immigrants? When you only speak the language of the country you’re considered an immigrant in? When your whole family only have passports from the country you’re considered an immigrant in? When you get told you’re white-passing or white or English or not-at-all Asian by other white people, other English people, other not-at-all Asian people? Or when your grandparents, the last generation who knew what being an immigrant really is, really was, have passed away and all that remains are some English people with slightly darker skin and foreign-sounding names? My parents aren’t immigrants, and I am certainly not. Why is there a category of immigrant for us to fall under?

The experience of immigrants in our country is so diverse, so heterogenous, so varied that I can’t write a piece about what being part of an immigrant family is. There is a shared struggle and a shared joy that I believe all non-natives in the UK must feel, but I don’t think it extends much further than that.

The experience of a third-generation immigrant differs so much from that of a second, and in turn that of a first-generation immigrant, that I cannot begin to compare my life with my parents, or my parents’ lives with my grandparents.

I was born to two people who were born in this country. They grew up wearing Western clothes, listening to British 80s music and watching the same television as every other person growing up in Britain at the time. They understand all the references that you could expect a middle-aged, middle class doctor to understand and they can appreciate my desire to listen to Western music and dress like my peers and eat fast food. We don’t argue about English culture, I don’t have to teach them anything. Our disconnect is that of a Gen Z/late millennial talking to a Gen Xer. We eat Iranian food every now and then, but with a fraction of the salt and sugar and usually no red meat. They don’t mind their son’s veganism, because they were vegetarian for 20 years when they were our age. We don’t have to explain to them that it is possible to cook without meat, and that maybe it’s a bit healthier too.

Looking back a generation, the same can’t be said. Even 30 years after her son first stopped eating meat my granny still struggled with cooking Persian food to accommodate the growing numbers of vegetarians in her family. My grandma never understood vegetarianism because it didn’t exist in her culture.

My friend, who was second generation (her parents were both born in Asia) always used to envy my parents, and the relationship I had with them. My mum loved the same TV shows as her whilst her parents were completely against her watching any television that contained sex or violence or expletives. My dad engaged with the music I listened to and introduced me to some of my favourite artists. Her mum listened to classical music and wouldn’t let her play anything modern or Western in the car or in the house. There was a disconnect between them that maybe will never be bridged. Or maybe they’ll be like my grandparents, who have been Westernised bit by bit as they aged and now send me and my mum TikToks and watch the latest big Hollywood films before I get the chance to. I know a very different version of these people than their children knew, when they couldn’t bear to watch physical affection on telly and would only cook Persian food.

My grandpa still recites Persian poetry to his grandchildren (who have no idea what he is talking about) and my grandma cooks modified, healthier Persian food for her family. But they care about the country they live in, more than a lot of born-and-bred Brits. They are heavily invested in the politics of our country, critical of our government and protective of our democracy. The country they were born into is lost to them now – democracy is something to learn about in history books in Iran but cannot be found in the country’s political system, and freedom (of speech, of worship, of press) has been lost entirely. Our country may seem broken, but my grandparents know it can be fixed. This is the country they met each other in, half a century ago. This is the country they raised their children in, watched them leave and study at university, watched them in turn have children. This is the country they’ve had jobs in – serving others always in their jobs. A teacher and a doctor, a magistrate and a lecturer.

It hurts them to watch politicians take office who see immigration as a disease, a problem that needs to be fixed rather than a blessing to be celebrated. It hurts them to see the divisions of this country grow deeper, as the rich are elevated higher and those below the poverty line fall deeper and deeper into degradation. I see the faith they have in this country, but I also watch as it is damaged by the decisions people make – to leave the EU, for instance. That day broke both their hearts despite it being their children and their grandchildren who will suffer the consequences most keenly. I wish I could see this country through their eyes. They aren’t naïve – leaving somewhere like Iran, it is impossible to be idealistic, I think.

Sometimes I think I’m lying, or misleading others, when I say I’m Iranian. What makes me Iranian? Not my words, or my clothes, or the way I interact with others (I haven’t adopted any of the Iranian cultural norms that I come across in the Iranian community). I’ve only made a few Iranian dishes, and I look up the recipe in a cookbook almost every time (except for when I ring my mum). I took a Persian rug and Persian tablecloth to my university accommodation in an attempt to feel more connected to my heritage, but it ended up feeling performative and fake. Even though both items were on show in my home for my whole childhood, I didn’t feel I had the right to display them in my own space. I desperately wanted a tattoo of my grandfather’s Persian calligraphy, but again, it felt wrong. I can’t read the language – how would it be different to all those embarrassing tattoos people get in ‘exotic’, foreign scripts which they cannot read or comprehend?

I thought if my name sounded more Iranian, or my parents had brought me up to speak Farsi, or I’d shown more interest in what makes Persian rice different (and superior) to other ways of cooking rice, or listened to and memorised my grandpa’s poetry, then I might be authentically ‘Iranian’. I might not feel ashamed or false when I assert my (three-quarters) Iranian genetics. I could spend time studying the history, reading about the Persian Empire or the religion of my forefathers (Zoroastrianism), use the past to trigger a connection to a country that is now only really a past to me and my family. I can pour over the sepia-tinted photographs taken by my grandparents which feature shiny, tan, smiling versions of my parents, with faces which look like the face I once saw in the mirror (when I was that age as well).

I may feel a loss, that at four or five or six years old (everyone is a bit hazy about those trips) they had experienced a country I cannot, that my childhood will forever remain bereft of this country that accounts for 75% of my history and heritage. They have memories of the Shah’s palace and huge, sweet watermelons and the oppressive heat that kept them inside all day, and the people they got to call family – aunts, uncles, cousins, great great grandparents. The only family I know are the family who left, who found a new life in the West and became part of the present for me. There was the lost family of Iran, whose names I will never know and whose faces I will never recognise, and there is the family of my world – great grandparents, great aunts and uncles, second cousins once-removed – who continue to exist for me. I hear their names, I see them as much as one might hope to see their extended family, certainly as much as I have seen my English family. They are a part of my consciousness and my familial sense of self in a way that the extension of me that must still exist in Iran is not.

I don’t really know the proper way to celebrate Now Ruz (Iranian New Year) or the names of the vast majority of Persian dishes, or any words in Farsi beyond tiny greetings, or the proper way to pronounce the Persian nursery rhyme about a cow that my grandma used to play with me. I cling to my grandparents for many reasons, and I am sure that one of them is that they represent a part of me that I will never get any closer to – they are my connection to the country that defines so much of who I am (beyond simply the presence of my ethnicity on every single form I fill in).

My own curiosity may lead me closer; perhaps one day I will take language lessons or read more than a few books about Iranian politics/history/culture or go through every single recipe in our more authentic Persian cookbooks. And there is a considerable chance that Iran will open itself up to the world in our lifetime (and my family’s religion will not be a reason to be arrested and/or executed). After all, I can’t pin all my heritage on my aging grandparents.

Art by Ananya Jain