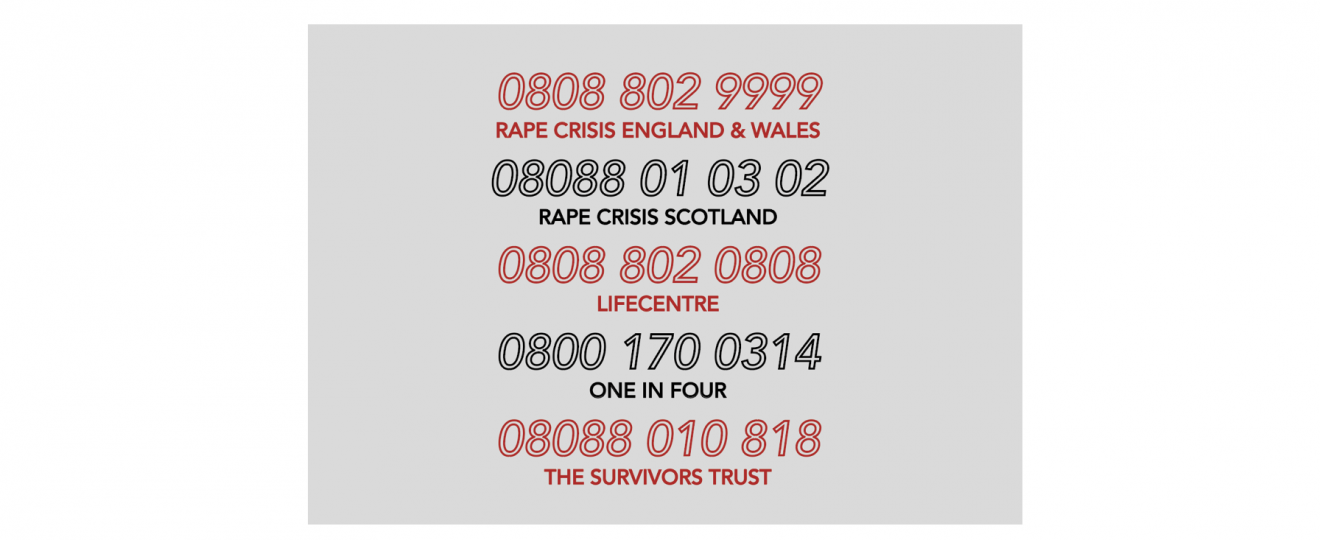

organisations offering support to survivors of sexual abuse in the UK

[Editors content warning: reference to sexual assault.]

According to YouGov statistics, 97% of young women have experienced sexual harassment. What that means is-

What that means is the single most universal aspect of womanhood is being a victim of harassment. It’s not having children or getting married or having a job or falling in love or-

What that means is that what we share is feeling unsafe. Feeling pissed off when we see a scene in a film where a girl is walking around at night, unbothered and undisturbed. Because that’s not life as we know it – is that life anywhere? We share the knowledge that if we wait till after dark to go for a run we will spend the entire period on edge, on high alert, maybe even without any music playing. Total silence in our ears except for the sound of our heartbeat and the outside world that we can be so deadly afraid of.

Did everyone else have a particular part of their walk home from school that they would sprint through in the autumn and winter when sunset was at 4pm and darkness cloaked the journey home? Sometimes with a key between your fingers, sometimes loudly on the phone, sometimes just an all out sprint to the finish line where you can see street lights and cars and the safety of visibility.

Did everyone else’ parents make them send them a picture of the number plate on the back of their taxi on the way home from a club? Because you were drunk, it was dark, the taxi driver was always a man and sometimes the last 20 minutes of the drive you would be alone. That’s something from my teenage years I’ll never forget.

‘My parents are so strict, my parents are so overbearing, my parents are so paranoid’.

Did I ever really believe that? Was I ever so naïve, to think that such actions weren’t justified, weren’t rational? I will never stop sending people the taxi number-plate when I’m drunk or it’s dark or I’m alone.

The death of Sarah Everard, like every other young woman, is my worst fear realised by another young woman. The tragedy of her death tells me that I was never foolish or cowardly or silly to sprint home through that dark alleyway. My parents weren’t paranoid to ask for the number plate of all my taxis. The fear that breeds in women, that becomes sharper and more focused as we grow up, is a fear of reality. Not a fear of the dark, of monsters or of our imaginations. A fear of the world we live in, that has told us year after year that we are in danger, that our lives are at risk, that we are never safe.

***

I cried the morning I saw that statistic. 97% of young women. I cried for 16 year old me who felt so alone, who used to laugh and make stories of her assaults because she knew the boys would be laughing about them too. I cried because she had to hear so many disgusting things said about her in the school corridors, in classrooms, in the common room. ‘Is she a lesbian? Because that would be really cool to see.’ One time a boy talked about hypothetically one day fingering me, in an art room, in front of everyone. We had never even spoke, and it was meaningless and funny and just a joke and not a big deal and even the girls are laughing Nadia so why can’t you laugh too? So I laughed and then I felt like I had given my stamp of approval, for all boys to say things about me that were disgusting and invasive and unbearable.

I cried for 18 year old me, who learnt that even if nothing you have ever done was your choice, nothing was your decision or was consensual, people will still talk about you as if it was. And no one you know has ever said that something wasn’t consensual at this point, so that word barely filters into your consciousness. So, you just try to laugh or pretend you aren’t listening.

If you’ve ever wondered what we talk about when we’re alone, when there aren’t any boys around, I can tell you now that we talk about this. Why wouldn’t we, when it’s the thing we have in common? The shared experience of being a girl, or being raised as a girl, is being scared. It’s being harassed and assaulted and abused by people we know and people we have never met. It’s sometimes walking home from the doctor’s surgery and getting cat-called three times in a row. By the last one, you start crying (because they leaned out of a car window and you could feel their breath on your face and you didn’t know if they were following you). It’s only sticking up the middle finger when they are so far gone that there’s no way they’ll see, because even though it is midday everyone pretended they couldn’t see when that happened so maybe everyone will pretend they can’t see if something worse happens.

This is what makes us girls. We sometimes don’t feel like we’re in possession of our own bodies – they’re just a feast for the rest of the world to help themselves to, to devour and attack and steal. Our bodies are land to be invaded, they’re a work of art to be commented on and ogled and criticised. Everyone owns my body, my face, my self. They speak about it like it’s theirs, they touch it like there’s no owner to ask permission from, they grab it in the street when it’s your 18th birthday and you’re wearing a brand new sparkly dress and you’re not at all drunk and you’re waiting to cross the road with your friends. Then you return the dress because it doesn’t look like an 18th birthday celebration anymore, it looks like the hand that was on your arse. You don’t tell your parents because they don’t like you wearing short dresses for this very reason. Just like you didn’t tell them when you got drunk and passed out and then woke up whilst something was happening to you that had never happened before and that you had never said was okay. Because you were drunk therefore, obviously, of course it was your fault.

These are the things we have in common, the things that tie us to each other and the things that make being a woman sometimes completely unbearable. I am a sculpture trapped inside a glass cabinet, eternally on display. If I choose to hide myself, I’m hiding from them. If I choose to show myself, I’m showing myself to them, I’m on display for them. I’ve been on display since my hair grew out and my clothes started showing my body, and since I was walking home in my school uniform aged 15 and a man yelled obscenities at me from a van. An adult man.

What that means is that every boy I meet is fighting the image of men that all those other boys have painted in my mind. Every boy who objectified me at school, every man who cat-called me on the street, every person who groped me in a club, every man who assaulted me when I was drunk or when I was sober. There is a separation in my mind. My father, my brother, my uncle, my grandpa, my cousin. The male friends I’ve known for years. My boyfriends. Some of the boys I once liked, who once liked me. The men who aren’t men in my head, but rather people who I trust and feel comfortable around.

Then there’s the unknown. There are men as a whole, as a section of society, that I fear. On some level, I fear them. I feel uncomfortable, I feel suspicious, I feel anxious. I have to wait a while before I let my guard down, before I allow myself alone in a room with them. It’s about safety, to put it simply. It’s about the panic attacks I used to get when I was alone with men I barely knew, the anxiety I feel even now when that’s a vague possibility. It’s a fear of men, it’s a fear of danger. It’s a survival instinct.

I wasn’t alone when I was 18, or 17, or 16. I didn’t know it, but some of the people I loved the most in the world knew exactly how I felt. We didn’t tell each other for a while, because we didn’t understand. We didn’t know what was happening or why we felt weird about the things everyone else seemed happy about. They didn’t know that a boy pressuring you into not wearing a condom was wrong, I didn’t know that if you were unconscious it wasn’t consent (even if afterwards you pretended it was). We told each other these things, how we felt about those occasions that everyone knew about, bit by bit as we got older. Consent became something that was discussed a lot, and we gradually understood what a healthy sexual relationship meant. We realised that every boy who had ever touched us had chosen not to respect us, and we realised we weren’t okay with that and we had never, ever, been okay with that.

We shared stories that traumatised us to the point that we carried them around like heavy weights that we thought about every time we were at our most vulnerable. We shared stories we had forgotten about, and only in speaking about them to a fellow survivor did we realise quite what they had done to our perception of men, our relationship with sex, and our view of ourselves.

The knowledge that I am so far from alone in this – my individual experiences are part of the collective, shared pain of women everywhere – is a bitter pill to swallow. It is the reason I can speak about it with my friends, it helps ease feelings of isolation and separation, but it is also a great, unspeakable tragedy for humanity. The women of our country, our society, our world, are unsafe and targeted. I’m at the age where we are speaking out – sharing stories on social media, having extended and empowering conversations with each other, writing articles and signing petitions. I think society is at an age where it is slowly becoming okay to speak out – the pain isn’t erased, these statistics aren’t going away or improving, but we have voices now that as a collective we previously didn’t. I don’t feel alone, in the way I did when I was 16. I can put a name to my experiences (illegal, immoral, violent, invasive) and I can share them with my sisters.

We grew up singing along to songs, not knowing that the words were disrespectful, degrading, dehumanising to us. We grew up immersed in the culture of slut shaming, objectifying, sexualising. We have been victims of slut shaming and yet we, unthinkingly, naively, participated in it as well. We experienced so much without knowing what it is – experienced harassment without knowing it had a name, experienced objectification without knowing that the actions of the boys in our classrooms were robbing us of our sense of self, our self-worth, our ownership of our bodies. We didn’t know that what happened to our friend was assault, and she didn’t know it either. Not at first. We didn’t suddenly become victims of harassment, assault, abuse. We slowly, painfully, traumatically grew to understand that what had happened to us was named, was illegal, was morally reprehensible and had dehumanised us. It had warped our view of men, of sex, of love, and vitally of ourselves and our precious bodies. This is the experience of being a woman. You slowly tell people – your friends, strangers, your parents. At first the knowledge is so scary and alien that you don’t understand it, so you share it with anyone. You still joke about it, but in a much darker, more self-aware way. Then you realise that you can’t throw this trauma around like it hasn’t altered the very fibre of your being, and you speak about it carefully, with a select few trusted sisters and maybe a romantic partner. Then you find that you need to cry about it. You need to cry about it on your own, and with your friends, and to your parents. You have so many tears – there was a blockage, and the last five years have seen a river build up, held back by this damn of denial and ignorance and confusion. And the process of accepting the pain of being a woman, growing up a girl, is sometimes too much to bear.

Then you think. They know how it feels. They feel this, they have felt this or they will feel this. Their own, individual, unimaginable, experiences of womanhood, have led to a similar destination.

This is unequivocally a men’s problem. Women don’t catcall other women. The numbers of women assaulting, harassing and raping men or women mean that whilst any kind of sexual violence committed by a woman is wrong, it is not a societal problem. It does not control and damage the lives of men in the way that we have had our own lives controlled and damaged by men.

My social media feeds are flooded with posts about these two recent tragic announcements: the disappearance and death of Sarah Everard, and the statistics from YouGov. My social media feeds are flooded with women posting about these two recent tragic announcements.

Men have been terrifyingly silent. As though the fact that they don’t believe they have committed any of these crimes means they can step out of the narrative. As though this is a woman’s problem, and a problem caused by a small minority of men they do not interact with. As though none of their friends have ever harassed a woman, made her feel unsafe, have assaulted a woman, have objectified a woman in school or at work or on the streets. I have been objectified and harassed at school, by my peers, at work, by my colleagues, and on the street, by strangers. Of my close female friends, perhaps every single one of them would say the same. What this means is, ‘not all men’ is a phrase that should be discarded from our vocabulary when discussing these issues. If 97% of women my age have been harassed, then ‘not all men’ is irrelevant and destructive. Enough men. And, enough men have said nothing. Enough men have said nothing when they saw a girl catcalled, when they heard a girl accuse their friend of assault, when they learnt that a boy in their sports club was on trial for rape. Enough men would only defend their sister, their mother or their girlfriend and not any girl on the street or in the club or at work or in the classroom. Enough men think that not being personally responsible for assault or rape means they can say ‘not all men’. They don’t understand that their silence makes it so much harder to bear, so much heavier to carry, the weight of womanhood. They don’t understand quite how different life is when you think about your safety every single day, every single time you walk alone, every single time you hear a car horn or see a man look at you as he passes you in the street. They don’t understand quite how different your view of yourself is when you think that more men have commented on your appearance than haven’t.

Brilliant & very painful perception of our collective reality. Keep speaking up. We are listening ❤️