Landscapes have been a popular muse of Western artists since the seventeenth century. Marshmallow skies, abundant harvests and tempestuous seas possess timeless attraction to painters and audiences. Something about nature is magnetic; humans feel compelled to replicate both the flawless and the decrepit. Is this allure based on aesthetics? Or is there a deeper rooted, instinctual appeal that reminds us of our provenance?

Most of my favourite paintings are landscape, and, in a typical Art History student style, Monet, Watteau, and Claude line my bedroom walls. It is safe to say that French landscape painting is experiencing an outstanding revival in mainstream popularity. The delicate pastels and flower carpeted gardens of Monet are readily available on Etsy. Similarly, Matisse’s bright and blockish abstract pieces can be found on the walls of many twenty-something-year-olds. For me, landscape paintings adhere to the cliche of ‘bringing the outside inside’. They evoke a sense of space, vastness, and fresh air – something we could all do with after being shut inside for eighteen months.

But if Poussin or Claude were alive today, would they still have the miles of unspoiled countryside to inspire their painting? Of course, many artists included mythological structures and characters in their work, but nature usually presented an idyllic canvas for them to explore other ideas. Do artists in the twenty-first century still view nature through this lens? The landscapes I am accustomed to in the news depict melting ice caps, vicious bushfires and relentless flooding. As our generation scrambles to salvage our planet, where will landscapes stand in the world of art?

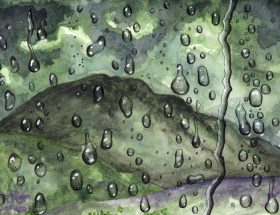

According to the hierarchy of genres, landscape painting was not a particularly prestigious form of art. History painting, portraiture and genre painting were considered more distinguished than landscapes, both to produce and to own. However, during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the demand for landscape paintings in Europe rocketed. In particular, landscapes became integral to Dutch culture; they usually depicted a realistic Dutch port or countryside, with earthy tones and gloomy skies. Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindart Hobbema epitomised seventeenth century Dutch landscapes. In contrast to earlier painters, both Ruisdael and Hobbema used accurate lighting and vegetation in their works, creating realistic scenery, rather than wildly idealised representations of The Netherlands. However, this ‘realism’ should not be overplayed; the reality of those working on the land was rarely shown, and both painters happily indulged in the narrative of a quaint Dutch countryside.

On the other hand, some landscape artists preferred to paint more idealised scenery. The French tradition favoured soft and touchable skies that made the viewer long to be elsewhere. Claude Lorrain is remembered for his influential sunsets and skies, most of which were painted during the mid 1600s. Claude frequently included mythological subjects or motifs in his paintings, whilst minimising human presence. His work embodies an atmosphere of silent grandeur – poverty is rarely depicted, and the sky and sea look warm and inviting. Despite his nationality, Claude was painting in Rome, and often encompassed Roman ruins within his landscapes. By juxtaposing the ashes of an ancient city with enchanting light and tone, he curated a melancholic magnificence.

Seventeenth century landscapes rarely incorporated a moralising purpose, and often the composition was idealised to lead the viewer’s gaze to a certain focal point. In my opinion, the prosperity and wealth paradigm, which alludes to the symbolic nature of harvest and nature, often drowns out the aesthetic aspect of such paintings. Each genre of painting holds its own merits, but for landscapists, the ability to evoke a sense of smallness in the viewer, and ineffectiveness of human activity, is undoubtedly their greatest feat. Indeed, land represented prosperity, as it was relied upon for food and wealth, but this did not guarantee human control over it. Nature was an unpredictable and limitless force and spectacle.

But we are no longer silent voyeurs. Instead, we have become corrosive trespassers, desperate to redeem ourselves. An appreciation of nature is instinctive to this generation, which suggests that our relationship to the natural world has changed following centuries of industrialisation. Having witnessed mass destruction of the environment over the last decades, we can understand the preciousness of nature. Even if it is for our Instagram feed or bedroom walls, nature is progressively cherished as it slips away from us. Its unpredictability and sovereignty has been fully realised as we watch communities be swept away by floods and cities shattered by earthquakes. There is nothing soft or inviting about our seas or skies.We have poisoned them and now they are retaliating.

When I look at landscapes painted 400 years ago, I feel nostalgia for places I’ve never visited, places that don’t presently exist in the same silent and beautiful way they used to. If I go to take a picture of the countryside view I wish I could edit out the telephone masts and smoke churning factories like Claude erased the impoverished. Consequently, studying landscape paintings should not be disentangled from conversations about climate change. In fact, they should be considered as constant reminders that humans were once temporary passengers on an earth that will outlive them. Historians must recognise that as our relationship with nature has changed, so too must the way we discuss changes in nature. Artists must also endure this transition. Using landscapes to make humans feel small and ineffectual is harder as our surroundings remind us of the ways in which we’ve manipulated and controlled our planet. We are also at its mercy, begging for its forgiveness – which leaves us to question, how then, will this be painted?