“Hair is everything. We wish it wasn’t so we could actually think about something else occasionally. But it is. It’s the difference between a good day and a bad day. We’re meant to think that it’s a symbol of power, that it’s a symbol of fertility. Some people are exploited for it and it pays your fucking bills. Hair is everything.” (Fleabag, series 2, episode 5)

A secret highlight of my year was in March, when a friend’s flatmate (who I had met only once before, the previous year) exclaimed when he saw me: “Lizzie! I almost didn’t recognise you – your hair is so different!”

My hair was indeed very different. In the space of a year, I have run the gamut of shades and lengths and, looking back at photos recently, prompted me to ask myself what I really thought I was doing trying to pull off a blunt bob. Of late, I have changed my hair again, and had a fringe cut in, something I have wanted to try for many moons and only now worked up the courage to do. But as I watched the seaweed tendrils drop to the floor; and subsequently examined the effect of it fronting the puffy, brown cloud of a perm-in-the-later-stages-of-growing-out, I was given pause to think. I entangle so much of my identity with my hair, and it seems that whenever I feel restless, powerless or just plain bored, the first thing I look to change is the crop of dead strands of keratin and other assorted proteins growing out of my head. And as it is wont to do, after that initial germ tiny seedling of an idea, followed the bigger and far scarier question: why?

In the world around us, women’s hair has been scrutinised and revered by international cultures since time immemorial: from the ancient Germanic tale of Rapunzel, who must have spent a small fortune on leave-in conditioner on her legendarily long locks, to the Chinese torture of the Spring and Autumn Periods (770-476BCE) kun, which required transgressors to shave their heads as an affront not just to the body, but to the soul. In literature, Patrick Süskind’s infamous serial killer Jean-Baptiste Grenouille hunts through pre-Revolutionary France, using his peculiar sense of smell to single out victims on the account of the scent of their hair, later using it to make the titular Perfume. Lady Gaga’s 2012 album, dedicated to individuality and the celebration of uniqueness, Born This Way, includes an anthem of an ode to the hidden power of hair, called, rather baldly, Hair. Gaga laments her parent’s interference with her self-expression by means of hair, and the liberation it affords her. Indeed, she belts out in the chorus “[she’ll] die living just as free as [her]”. In our collective cultural lexicon, various phrases and references to things such as “wigs being snatched” and “weaves” have slid into regular use by way of an increased awareness and discussion of the history and cultural significance of hair in black communities. We talk about “letting our hair down” when we finally shake off the rigours and conventions of the daily grind, and a tense situation is ‘hair raising’; and if we escape whatever situation that is, it is often by a ‘hair’s breadth’ (or, a ‘bawhair’, as the Scots vernacular that I love so much so charmingly puts it).

Conversely, and yet somewhat unsurprisingly, it would also appear that the lack of hair, particularly in women, is something to be abhorred. There are countless cinematic iterations of female characters, who, in times of great stress or emotional upheaval, cut all their hair off. In researching this article, I watched a video that was entitled Haircut Supercut: When Women Lose Their Manes and Minds on Screen, and I would urge you to do the same. The narrator questions the misogynistically reductive treatment of women’s mental health onscreen, by way of this culturally repetitive visual motif of hair cutting or head-shaving in topically diverse films ranging from twee-if-cult-teen-romp Empire Records (Moyle, 1995) to hard hitting, based-on-real-events crime drama ‘The Accused’ (Kaplan,1988). Historically, a strong thread of shame can be found woven into the act of female head-shaving; indeed, many refer to it as a form of mortification of the flesh, or disfigurement.

Since Biblical times, the act of head-shaving has been conflated with prostitution, and the position of the ‘shorn woman’ as undeserving of the head-covering, a status object befitting only married women. Throughout the ages and in many religions, head-shaving is a documented punishment for adultery. On entrance to the Victorian poorhouse, heads were shaved as a preventative measure for lice, an undertaking simultaneously demarcating the women in question as morally reprehensible enough to be poverty-stricken. At the end of the German occupation of France during the Second World War, women who were seen to have collaborated with the Nazis (even prostitutes who were rumoured to have serviced German officers) had their heads shaved as punishment for their transgressions.

Who could forget the controversy and constant commentary in 2007 when pop sensation Britney Spears shaved her head during a period of intense stress around her divorce? The ten year anniversary of the ‘event’ two years ago prompted a whole new raft of jeers, ‘remember- when’s’ and memes at the expense of what Spears herself described as an act of small rebellion in the face of an industry and a world that had robbed her of her autonomy from a very young age. And yet, the images from that period are still described as grotesque.

She’s not grotesque; she’s just bald. My mum’s granny took to wearing wigs in her later years as a way to hide her hair which was thinning due to age and decades of damage by way of backcombing and clouds of hairspray. ‘The Witches’ by Roald Dahl, in its most terrifying scene, sees the coven remove their wigs and turn from ‘normal women’ into hideous, bald monsters.

There are vast amounts of resources online for people dealing with cancer, and the impact of hair loss as a result of chemotherapy, alopecia, thyroid disorders and menopause. Conversely, people shave their heads in support and in order to raise money for Cancer Units among other charities. It would seem that through our collective cultural obsession with hair as a marker of health, sexuality and fertility, female baldness has become a signifier of the three great woes of womanhood: madness, illness and ageing.

As an aside, in the face of all this demonization and othering of the bald woman, might I recommend looking up the #omgshesbald movement on Instagram. Also read Jo Shapcott’s brilliant and moving poem, Hairless: an exaltation of the state of female baldness, and an antidote to the constant intertwining of head-hair and female sexuality and beauty.

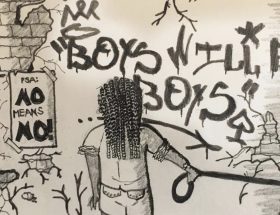

Hair has become a tool by which to discriminate, and not just by the lack of it. Countless cases of employers sacking black employees, telling them their hair is ‘unprofessional’ and ‘unacceptable’, point to yet another level of racial stigmatisation and bigotry, intersecting with an additional unfair and unnecessary standard placed on women. Furthermore, in recent years, a worrying trend in the circles of high-fashion, and on the red-carpet, has led to controversy for several white celebrities, such as Katy Perry, Cara Delevingne and any number of the Kardashian/Jenner clan, coming under fire for wearing their hair in styles such as cornrows. While, superficially, this may appear a minor issue in the grand scheme of institutionalised racism that our society is subject to, the actions of these women in appropriating traditionally Black hairstyles for simply edgy-style-fashion, without considering both the historical and cultural implications of their actions, suggests an apathetic disregard among the upper echelons of our perceived ‘elite’, especially when they make no use of their highly privileged status to advocate for any pro-Black movements, not even Black Lives Matter. The problematic nature of this subtle form of ignorant racism is thrown into sharp relief when one considers the storm that was whipped up when Zendaya, a Black woman, wore dreadlocks, a traditionally Black hairstyle, on the red carpet. She had insults hurled at her from the fibre-optic fortresses of the internet; the most glaring example of which came from Fashion Police’s Giuliana Rancic, who suggested that Zendaya’s dreads made her look like she “smells like patchouli oil. Or, weed.” It would seem that the white-centric, patriarchal society in which we are currently trapped would have us believe that not all hair is equal.

At the start of this article there is a quote from the hit BBC series Fleabag, which ends with the mantra-like proclamation from the eponymous heroine of the series: ‘Hair is everything.’ And it would appear she is correct: not only can one tell almost everything about an individual’s recent health history from an analysis of a single strand of their hair; we would be told that women’s hair holds at least half the weight of their whole identity, and whether that hairdentity is perceived positively or negatively is bound up with questions of race, age and sexuality. With such vast swathes of our personhoods being meshed into it, it is no wonder that in these times of greater liberation, hair has become an integral tool of transformation and self-expression. In a world that seems increasingly out of the control, to change one’s hair could be seen as a way to change oneself, and then by extension, one’s immediate circumstances. A drastic haircut can render you unrecognisable to even your nearest and dearest— it’s quick, its cheap, and more often than not, you can do it yourself. It can be an ethical change too: hair is increasingly becoming a more environmentally conscious industry with the rise of movements such as #NoPoo and the radical increase in sales of shampoo bars as opposed to traditional plastic bottles.

Greta Thunberg, the environmental activist, with a face that seems so young for her sixteen years, favours two sensible plaits, and terms her autism a ‘superpower’ in the face of those comb-over wearing men in suits that deride her for it. There is sense and vision far beyond her youth in what lies beneath those plaits: Thunberg’s vision of the future is not an easy one to face but perhaps it is time to address our societal preoccupation with looking in the mirror, and start looking out the window instead. In an ideal world, we would all take a leaf out of Greta’s book, keep it simple and natural, and get out there and do something to change the bigger picture, not just the one of ourselves on Instagram showcasing that new asymmetrical lob that Vogue recommended.