On Reading Dylan Thomas Away from Home

It is summer and I am nine. My father and grandfather have driven me up to the valley. Through my window, which is dusty with the dry ground of a rare, droughty Welsh summer gouted and swollen with an unbearable heat (twenty-three degrees), I can see the aqueduct. It is ringed with foxgloves and green, mossed-over bricks. I thought that I would recognise it, somewhere, in my toenails and in the bones of my heels.

I do not.

—-

I am from South Wales. I am Welsh everywhere. I revel in my Welshness, almost to an absurd degree. I can hear it in my voice, as the accent comes harder and sing-songy every time I even mention where I’m from, or when I speak to my mother on the phone. That dusky, sensual Bridgend twang rings out of my tonsils like a silk-covered Calon Lan (if you aren’t from Wales and don’t know Bridgend, and if you haven’t heard me speak in real life and think I am being serious here, please note that that was sarcasm). I am more Welsh (Welsher? Welshier?) now than I ever have been in my life.

Because, before I left Wales, I wasn’t Welsh at all.

(This may be the hardest article I’ve ever written.)

—-

We park the car and I count the mud rings on the tire. My father and my grandfather get out, and they point at the switchback angles of the hills. When I remember said hills they take on the two-dimensional flatness of acute triangles, like the geometric tiles you’d play with on the floor when you are young and your mouth is sticky with orange juice and you have plunged your hands into too much mud and the sugar and the dirt seem like a perfect combination to improve your mathematical skills. I fiddle with my seatbelt and the sun comes through the window.

—-

Before I left Wales, it ceased to hold any appeal to me. Well, this isn’t entirely true. I liked my crooked little part of it-I live way out in the country, and down the road from me there is a humpback railway bridge where ivy pushes out the greying bricks and Himalayan balsam flowers turn their floating pink heads back and for in turn with the trains as they carve on by, like they’re watching a tennis match. There are two farms just a bit before the bridge, in the dip of the hill. One is huge, monolithic. It has a glossy, velvet green silo, the Ghallis tower of Court Colman, and empty barns that stretch on as far as the eye can see. It is abandoned, and the kudzu and thorn leaves and inch-thick layers of graffiti cushion any sound when you enter (for any fans of Resident Evil 4, my boyfriend says that it reminds him of the cultist village, which, there you go. Welcome to Wales). I always think that it would be much improved if there was a crumbling statue, a shattered visage half-sunk in the remnants of choking ivy, forgotten Strongbow cans and sweet, old mud, a sneering face of some red-cheeked farmer wearing a broken dai-cap. Under him these words would appear; I am Evan Evansdias, Farmer of Farmers; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! It would fit the mood a bit more.

On the opposite side of the road, where, if you’re following, the unmighty were meant to live and look upon the works of the mighty and despair, is the other farm. It is a collection of an old train carriage, loud geese, one or two strutting hens, and a soft lovely little dog who sticks her head through the fence for you to smooth her. This farm has triumphed and sat there, messily and rather proudly, for my entire life. It feels no need to proclaim its mightiness, unlike Silo Big Barn the Third opposite. It is bizarre and there are more unlatched tires than farm animals but by god, does the little guy try! If you’re like me, reader, you can’t resist an underdog. The other, that hulking monument to industrialised agriculture, has rotted away. You, reader, can make a point from that if you wish-it is not this article’s concern and I am perhaps far too lazy or not well read enough on the state of farming today to make it.

But, yes, Wales. I like this small, weird part of it where I can romp along like a forgotten aristocrat with my dogs and break into fallow fields and get my knees wet by high-grass and not hear sight nor sound of anyone else, and I must admit that I have always felt this way, even before I threw my red-spotted handkerchief over my shoulder and packed off to the wilds of Scotland. But this part didn’t feel like Wales to me. Indeed, it felt like my escape from Wales. When I left school at the end of the day and my brain ached and I didn’t want to be my school-or-person self anymore, this corner of the world felt like nothing and nowhere at all. In the summer it could be Edwardian England, and I could be a lazy daughter of the gentry, whose only concern iss whether taffeta was in this season, or which MPs’ son I would grant with my favour at my debut ball, and I could slink among the grass with my loping liver-spotted spaniel pretending to hunt for pheasants or whatever I thought the gentry did. (This is just a brief aside to talk about Kennedy, said liver-spotted spaniel. Just out of scientific curiosity, has anyone else’s Springer ever been mistaken for a bear? We’re worried that somewhere along the line there was a mix up and we received a grizzly by mistake. That would be very Wales for you. In for a spaniel, receive a bear. Keep being you, you rotund weirdo with your heart of gold and love for barking). In the autumn when the sun went down at four, I could wrap myself up in the twilight and gaze mournfully over the bridge and raise pumpkin people from the ground and become a skeleton madame of a Halloween world (if anyone’s interested I did write a story about these pumpkin people, which can also be found on BRIZO. Well, if you don’t promote yourself, who will?). In winter I would count the frosted hedgerows and listen to the robins and wonder idly about any nearby ice queens. In spring, the clouds of cow parsley and dandelion would make it seem likes I was on a separate planet with green and yellow cushioning and a blue empty sky. None of these places existed in Wales. They were entirely separate to and adjacent from Wales. I wouldn’t have liked them if I felt they were a part of the same place.

What you have to understand, here, before you crack out the pitchforks and get to burning me alive is that Wales and I were like two animals circling each other in some high-jungle clearing. Ones not too far removed, like a panther and a mountain lion (sorry, Wales, but I’m totally the panther). Or a snow leopard and a regular leopard. Or a cheetah and a tiger. You get the point. We had shared features: our mouths looked the same when we raised them just so, our eyes narrowed and bloomed together. Our paws were both big and padded. But our furs were different colours, or our yowls rang out at different pitches. We stalked around each other, looking to see whether there were more similarities or differences. It is the trick of my trade to exaggerate, and I did so at the start by saying I wasn’t Welsh at all. There were some moments where I was. When I was small and wild, scrambling over the bracken bay of Southerndown with my dad and hearing about the ship-wreckers who lured in sailors to their deaths on Dunraven Bay and the man who became a lord from salt-stained gold and built a secret garden for his wife; then I felt Welsh. (I have no idea if any of that is historically accurate, by the way, and I have no desire to fact-check it. I like that version). But Wales most of the time seemed stultifying, stagnating. There was only one way (well, two. I’ll get into that later) to be Welsh and though our pelts fit the same in some angles, Wales had bones in some places where I was flesh, and had organs in some places where I had joints. I couldn’t be Welsh, I couldn’t fit the very narrow measurements of the Wales I saw. And so I fled from it.

(‘Caitlin, you faker!’ I hear you cry. ‘All you ever talk about is being from Wales!’. And you’re right. If I’ve ever met you in real life, I probably introduced myself with ‘Hi, I’m Caitlin, I’m from Wales and that’s the most important fact about me.’ I did, didn’t I? And now, you’re wondering was this all for clout? Some half-hearted, Young Adult Novel Heroine attempt to be different? Well, stay tuned for answers. Ow, ow, move the torch back a bit! I don’t mind being tied to a stake, but would you mind loosening the ropes?)

—-

My grandpa smiles and opens the door for me. I step down and the ground is wetter than I imagined it would be; from the window, it looks dry and crackly but when my feet come down on it the earth sinks and releases a small puff of that rooty, damp sweetness of stored up water and vegetable skins. It has been a long day of catching up with brothers and uncles and cousins that I don’t quite know and I am a bit sleepy and overwhelmed. My grandpa tilts his head back to look at the late sun, and the light picks out all the warm lines baked into his face and for a bizarre moment it seems like he has grown straight up from the ground, like the oak trees fanning at the edge of my sight. He looks a part of this place, like even if he wasn’t here you would know where he was from, just by the crinkles of his eyes.

—-

What is Wales, then, I hear you clamouring for the answer. And I am so sorry to disappoint, but I don’t exactly know. All I know was that for a long time I wasn’t it.

Speaking Welsh, for instance. I can’t beyond a few phrases, and it aggravates me beyond belief. I feel like every time someone asks me if I’m bilingual on some level it feels like they’re asking me if I’m really Welsh, or just English masquerading as Welsh. If I hear someone speak it I am viscerally jealous, and afraid of them finding out I can’t speak it in return, and I feel a deep, bitter seed of shame take root in the wet mushroom ground of my heart, a shame that says they are Welsh. You are nothing.

I am trying hard to learn it now, thanks to the valiant efforts of the Welsh society at St. Andrews and the brilliant tutoring of George (if you’re reading this, George, I have learnt more with you in three sessions than in approximately ten years of schooling, and while I am more willing to learn now than I was then you are a singularly encouraging and illuminating teacher), but for the longest time I was proud that I couldn’t speak it. The people that I knew in South Wales (where it is generally rarer to have a full-Welsh speaker than in the North and West) that could speak it were of a largely singular type. Athletic, assured girls with a healthy glow on their faces from that time spent outdoors playing sports I was and am absolutely no good at, who could banter happily and let the language of our fathers roll from their tongues with the naturalness of fresh clean water crashing down a green mossy hill, and with an ease that I could only dream of possessing. An ease in the language, and an ease in themselves. I was still very heavily invested at that time in my resentment of other women as a means to make me both feel better about myself and allow me to be different and so I rejected Welsh as a means to further reject them, in some roundabout, horrible way. I would never look like that, or speak like that. I was awkward and always had about eight times too many bags that would crash into tables when I walked by and never felt that confidence that they seemed to carry about by the shedload.

That, perhaps, is the thing that never made me feel Welsh. In my mind, there are two ways to be Welsh. In the North, I thought they were delicate and druidic and soft, ethereal; a friend described the North Walian accent as ‘that lovely, whispering’ one, and let me assure you I definitely do not possess that. That was real Wales, a Wales with men who herded sheep and stood like bastions of the old world, skeleton dark lines in the field against the purpling sky. They had lamplight eyes and spoke like the sea crunching rocks in its watery maw, and there were women who would dry their large black petticoats under the trees, crushing fragrant herbs and blackthorn to make healing soups and fertility sweets.

I have just eaten a punnet of grapes and in a week have watched twenty-two hours of a YouTube Let’s Play of Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice. Do I seem like I hold that mysticism and grace to you, reader?

Then, here’s where the South Walian dimension comes in. (I love you, West Wales but you’re a whole other kettle of fish, one that I do not have time to boil). South Wales has been the site of heavy industrialisation, coal mining and port activity for a long, long, time (at one time Cardiff’s Tiger Bay was the centre of the coal trade for the world, and Swansea was absolutely decimated in the Blitz due to the strategic value of its docks). Creeping over the green that still characterises North Wales, the grey spread of cities and terraced houses and mining equipment hopped from valley to valley in South Wales from the late 18th century onwards. If you’re south of Swansea, you probably have an ex-coal site no more than fifteen minutes from you; my local is no more than five. Most of these have also been the sites of utmost tragedy. My nearest, mentioned above, was in 1892 the site of a terrible explosion that killed 112 men and boys. Now, after regeneration projects in the 1980s, it is utterly tranquil. Bees hum lazily about waist-high stalks of yellow rapeseed, and there is a still, slow lake bordered by blue, frozen grass and filled with golden-rust reeds that my dogs like to get lost in. You can find adders down there, and badgers, and soft robins with bloody chests.

That is South Wales. Beauty amongst unimaginable tragedy.

Mining, a profession slowly winding down since Thatcher’s gutting in the 1980s, still casts a very, very profound shadow on our homes and our towns. I was seven when I learned about Aberfan, a disaster in 1966 where a waste-tip of coal-slurry careened down the mountainside towards a small Welsh town, smothering the junior school five minutes into morning registration. It killed 28 adults and 116 children, wiping out the majority of an entire generation for that village, and leaving the children who were rescued under their desks from those suffocating graves of choking, black, coal-silt with a lifetime of survivor’s? guilt. The National Coal Board had been made aware of the dangers of the tip, did nothing, and then firmly resisted the attempts to clear out the remaining tips surrounding the village after the disaster. We learn about Senghenydd in 1913, the worst colliery disaster in British history, where 432 miners were killed in an explosion, with some bodies not being found till days later. There had been explosions before, in 1901, and on the 25th July of that year an independent investigator highlighted the extreme danger of the mine, made even more clear in 1910, when a falling roof created firedamp. We learn of the Merthyr Rising, and the Rebecca Riots (a bunch of Welsh farmers dressed up like women and went around burning toll gates down with appropriate theatricality), bizarre pockets of history that speak to a lifetime of exploitation and pain. South Wales colliers turned out in record numbers to fight in the Spanish Civil War and a collective of Merthyr miners sent funds to the Union army in America. They knew what it was to be expendable, forgettable. You know about these tragedies; you feel them in some bizarre, lost place between your collarbones as if you were there. This isn’t unique to South Wales, of course. However, it is funny to see such a small country with such vast differences in history, even in the sounds of the language, how it rolls about your tongue, from North to West to South. My friends who were brought up in North Wales learnt of the glory of the Welsh Princes, the brutality with which they were put down. We learnt nothing of Llewellyn, or Owain, at least not in my schools. Our histories, and our tragedies, were different, and coloured black with coal.

That is not to say that this shadow of mining is all bleak. Indeed, South Wales has a lot of fairly brightening history of culture mixing and immigration. If you go more than two generations back, you’ll probably find a miner amongst the sooty branches of your family tree. South Wales often isn’t purely Welsh beyond those two generations; a melting pot of American, Irish, English, South African, Scottish, German, Spanish, people of a thousand different nationalities flocked to Wales during the mining boom. Even in my own lineage, my paternal grandfather’s grandfather and my maternal grandmother’s father were both English (shock horror, imagine being repulsed by your own blood. If my English flatmate and best friend is reading this, I am only kidding. Reader, I’m not. No, no, I promise I am). That’s why Rugby is our national sport. If you track the history of rugby, the game we play now was actually invented in England in the early 19th century, rumoured to be in Warwickshire Boys’ School. It is a private school boys’ game. And yet, we have hymns and traditions and the Welsh old boys’ who have spent their lives underground or in industry (the furthest thing away from Eton and Harrow one can imagine) pour into Cardiff on game day. It was introduced into Wales in the mid-1800s by a Welsh boy who was educated at Eton and Cambridge and brought it back to teach, and it was taken up first heavily by English imports to Wales before we adopted it as our own. South Wales takes all sorts of threads and sews them into a weird, colourful tapestry.

Why, then, have I spent the majority of my time in Wales feeling like a dropped stitch?

—-

He is talking about the intricacies of where he’s grown up, and he’s pointing out-here is where I found my Roman coin, this place used to have new houses being built and we’d scramble amidst the rubble and jump off the roofs down to the construction fabric below, don’t know how we didn’t kill ourselves-places that beat in him, and I am thinking, where are my places that I will tell my children? I don’t know. My dad is smiling and interjecting with his own memories of my grandfather’s mother, or of the pub they drank in when he was younger, in a different town but with the same honey gloss of blissful nostalgia. My grandpa must notice my worry in the crook of my furrowed brow and points out a brilliant butterfly. It is black, velvety black, and spotted with a jewelled red. This red falls and curls in bands like ribbons in the night of its hair, and the edges of its rippled wings are pocked with white, like eyes. It is so close to us, dancing and nibbling on a bright green leaf (do butterflies eat leaves? I don’t think they do, but that’s what I remember it doing. A nine-year-old’s brain, right? Magical. They need to work out how to connect cameras to those things. We’d make millions in movies, you and I, reader. If you could only figure it out. What a disappointment).

‘That’s an admiral,’ my grandpa tells me.

‘Like-in the navy?’

He laughs, long and loud.

‘Perhaps. It’s a type of butterfly. We used to catch them. There are lots of rare ones around here.’

I see it, then. His life. The hum of the earth around us, the golden haze of transparent memories that must fade in and out all around him in this place. I cannot breathe them, like him, as they are not my own. But somewhere in my gangly arms and freckles they strike a chord. I know them, even though I have not been here before.

—-

For all its melting history, though, South Wales seemed to have set traits, certain rhythms, that I always seemed out of time with. There were the jokes, the ribbing, that I, as a generally agreed upon unfunny person, could not grasp, always a step behind. There were the songs that I, with all the tune of a broken whistle, could not carry. But there was a being. A lightness, a gaiety; for all the roughness of our history there is a certain buoyancy I did not possess. I would be a few seconds behind, or the fun fact I would interject would fall flat. Even with my family, or friends who have been friends for so long they are akin to family, sometimes I would be the puzzle piece that is all corners. As my father delights in saying often, (I know you’re reading this Dad), I am the changeling. Indeed, I do have some behaviours that make it seem like a real Welsh baby was spirited away and I, an odd little witch child, was deposited in their place (rum deal, sorry parents).

I don’t drink, or at least not often; although the stereotype is usually applied to the Irish, South Wales are also notoriously fond of a good, old-fashioned brew-down. I have tastes that run towards the macabre, or the weird. My poor boyfriend, when I was staying with him for two weeks I made him walk with me at least every other day to the grand old cemetery near his flat, through the crumbling, ivy-eaten graves in the fading twilight (the only correct time to go, of course) peering at the faded letters from the 1800s describing sudden drowning deaths or a man passing away after being taken ill from a cup of tea (definitely poison, right, reader? I mean, there’s no other explanation!) while monologuing like an Addam’s family extra on not being afraid of death’s beautiful, pestilent face. My passions and intense obsessions were not normal, and disjointed, and my own inability to make sense of who or what I was, what I wanted, how to be, led to a childhood and particularly an adolescence of feeling that really, Wales wasn’t for me. I didn’t quite fit in (I’m so sorry for the amount of Jughead Jones nonsense coming through here, I am really trying to avoid it the best I can) anywhere. I had friends, brilliant friends, but I never felt like I quite understood them. They seemed to connect to this Wales, this happy go lucky, take-it-on-the-chin boys, sing-song down the stadium, warm Wales where everyone knew who they were and were satisfied with their place. I understood, I felt, the tragic, weird Wales-the mining disasters, the highwaymen stories, the freaky traditions like Mari Lwyd (they stick a horse skull hooded in white on a pole and knock on the door, requesting entry in song. You have to sing back at them if you don’t want to come in, and it is a test of the wills to see who breaks first. If it’s you, Mari Lwyd and her carriers get to come in and have food. And somehow it is Christmas as a result? God, I love it. What theatricality! How macabre!). I was most Welsh when I read about them. But I felt too late for that; those traditions were dying and dead, and the tragedies were sunk in a mist-logged past century. This contentedness, this ease with people and place, this rough, happy charm; I couldn’t get it. I didn’t have it, as much as I longed for it. I was never satisfied with my place, or with who I was.

So I rebelled. Quite frankly, indeed. I wanted to be in England, or Scotland, or Ireland; all three of these lands occupied an entirely beautiful, and ridiculously artificial, veneer in my head. Silvery moss and pale firs. Empty, black moors and lonely, tumbledown estates with haunted corridors of gaunt, gilted, wild-eyed portraits that I could float down dramatically, alone and ghostly and macabre to my heart’s content, with no people around to not laugh at my terrible, long-line jokes or just pity me for being not-quite-right. The people whose town my blue-moon estate would hulk over would be something almost Lovecraftian, paranoid, quiet, or perhaps they would be villagers of old, red-cheeked and removed. I wanted to be in America, which in my mind was a series of violet, snow-capped mountains and empty, coyote-howl plains. I could be a cowboy, alone and not lonely under the endless skies, unbothered, distant. Wales seemed too alien.

But this is where Dylan Thomas comes in.

—-

It is summer and I am twenty-one. (Particularly eagle-eyed readers may have worked out that the summer I am referring to here is not the smudged one of memory but the one just past). I am in Swansea, in my grandmother’s house. My mother is boiling a kettle for tea out in her kitchen, and the house smells like pasty tart (for those unacquainted, imagine the hot corned-beef and onion filling of a regular pasty, and put it into a big pastry pie. It is…exquisite). My Nana, a similarly wild-eyed woman with a cloud of white-candyfloss hair and a penchant for the inappropriate, sits regal in her bright pink jumper and long, floral skirt that my mother bought her for her birthday in July. I like to ask her about our family, and her memories; she’s lived through a lot and likes to frame her tales through a particular brand of caustic, sarcastic humour that my mum groans and laughs at in equal parts from what she can hear in the kitchen. She is telling me about my grandfather-her husband-and how their first date was a Jazz night in one of the local theatres. My Bampa was a jazz fiend, this I know, and she tells me how she wanted to impress him.

‘What did you think, Sylvia,’ she mimics his deep voice, ‘I loved it, Gwyn!’ She then rolls her eyes and draws a hand across her neck in a faked throat-cut. We are laughing. She tells me about her father, and my Grandfather’s father, a union organiser (cool) that had a vicious temper and wasn’t very nice to his wife (not as cool). She tells me stories of when she was little: how she passed the eleven plus and had to walk thirty minutes and catch a bus to go to the grammar school, where she loved art and biology but hated many of the other girls.

‘Snobby madams,’ she sniffs.

She tells me what Swansea used to look like and knits together a sparkling silver city of bad smells from the docks and bustling shops and a father that swung her hand and bought her a china tiger.

—-

You’re thinking-finally. His name is in the title and you have taken 4,629 words to even get to him yet. He’s who we came to see, not your teenage angst ‘where do I belong’ ramble. I know. I do. But. I had to get you into the zone, didn’t I? Set some exposition. So here we are, ready to begin.

Dylan Thomas has equally cast a long shadow over my life of a much similar veracity to mining. Firstly, I write and he is by and large one of the only very well-known Welsh writers. He also came from Swansea, which is the seat of my ancestors (by which, I mean, my mother and her half of the family apart from that rogue English great-grandfather were all born there). Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly in my life, he is where I got my name. His wife was Caitlin, and on visiting Laugharne, a coastal Welsh town where he had his home in later life, my parents saw her name and loved it.

Thus, enter me.

But, for all of these multitudinous (Really? Yes. let me have this.) connections, I had never read much of Thomas’ work. Until this semester. We were set a research essay in my 1940s writing class and as I had spent the majority of that semester proclaiming my Welsh pride (it is always easier to love home when you are away from it, and just because I felt that Wales didn’t understand me and vice versa, did not mean I did not love the bones of that weird, warm country. People can be complex and contradictory, okay?) I felt that I had better write on one Welsh author. It was kismet. I could not complete my degree without strolling down the old Welsh path. Thomas was one that there was enough of a bulk of work from which to create an actual argument. What a nice little story, I thought, to tell the tutor, about my name and how I was excited to read Thomas because of that.

Then I began to read.

And I fell utterly, utterly in love.

His writing was bizarre and nonsensical, full of burning bodies and doppelgangers and winged people and darkness and rage and humour and ghosts, and I felt every beat of it. But more than this, there were the works of his childhood. In 1945’s Memories of Christmas he described the neighbourhood jokes-Mrs Protheroe banging on the gong like ‘a towncrier in Pompeii’ calling out fire, Mr Protheroe standing around saying ‘Well, isn’t this a fine Christmas Eve,’ the young boys losing their mind over the excitement, planning to ring all the emergency services to make it as DRAMATIC AS POSSIBLE: I sat in my chair and read this world rendered with love and as familiar to me as my own face and I laughed aloud. I could hear their voices, the nuances in tone that would make a completely ordinary set of words the funniest thing you could ever say. I tried Under Milk Wood next, and the characters sent me rolling-the crematorium head named Evans the Death was such a South Walian thing I couldn’t breathe. I read them aloud to my non-Welsh friends, and received pleasant smiles in return, but none of the raucous side-splits I had been afflicted by the previous day. This shared humour, this relation, this sketch of people who existed in the South Wales of eighty years ago resonated with me now. They may have lived in a different time, but their faces, their speech, their oddities-my face, my speech, my oddities-remained almost static. It was then I realised that I was not divorced, a nationless woman desperately in love with a country that she did not gel with. We had a shared secret language, a secret humour, that I knew! I was in on the joke! For all of Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities, I had never been able to imagine myself as belonging to Wales, but Dylan told me I did. And I longed for this home, reading him. I couldn’t wait to step down from the train, to quote another great Welshman (Tom Jones, for the philistines amongst you). It felt like home would be waiting for me, ready to embrace me in its beautiful, odd patchwork quilt in which I no longer marred the pattern but understood it. Reminiscences of a Childhood furthered this realisation that yes, actually, perhaps I am the Welsh I have so desperately tried to be. In two neat little paragraphs Thomas had summed up the entirety of the South Welsh experience. There is no way I can capture it in short so I’m going to include it here.

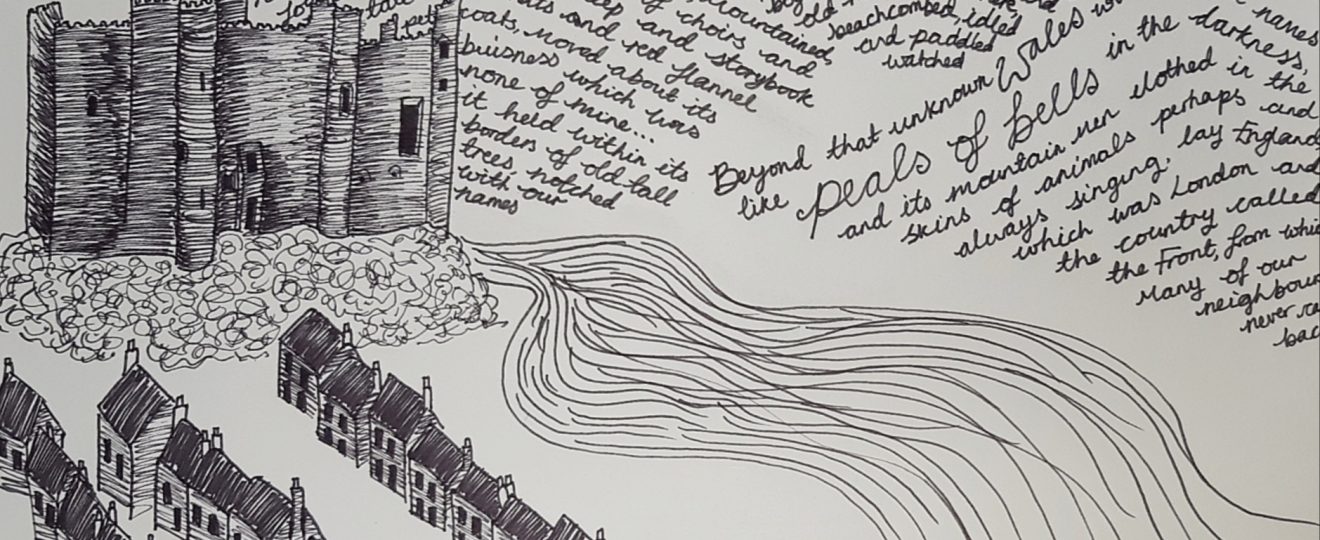

This sea-town was my world: outside a strange Wales, coal-pitted, mountained, river-run, full, so far as I knew, of choirs and football teams and sheep and storybook tall black hats and red flannel petticoats, moved about its business which was none of mine.

Beyond that unknown Wales with its wild names like peals of bells in the darkness, and its mountain men clothed in the skins of animals perhaps and always singing, lay England which was London and the country called the Front, from which many of our neighbours never came back. It was a country to which only young men *travelled.

South Wales. That is it. The constant, creeping feeling that you are not truly Welsh; that the real Wales, the bone deep song of the land, is spirited away in distant, dark, mountainous places beyond the North Walian border. A Wales that perhaps thrummed in you somewhere along a lost sugary bloodline, but a Wales that you could not ever partake in, an old Wales, a real Wales. That phrase, ‘wild names like peals of bells in the darkness’; God, what a collection of words. I can hear it in my throat, the bright, river-run language, the lost, starry hills. If I live to be a hundred I could never sum up such a lonely, lovely, untouchable (maybe unreal-the debate about hiraeth, homesickness and nostalgia for a home, a Wales, that has been lost to time, is a debate that I will not wade into) place with such beauty and grace and sheer casualness.

But yet, you are not England, either. That is a place for the young and the smart and the bright, and even when you are there you do not belong. One only needs to read Alun Lewis’ short stories, where the eponymous Welshman amongst the English is called Taff and only fits in amongst the fringes, to see that. You do not feel that that culture, the culture of high tea and manners, belongs to you either. We are stuck between, a whole chunk of a country unmoored. And it made clear to me that perhaps this sense of unbelonging was not sole to me, and perhaps in its disjointedness I could find a joint. Maybe in the collective unbelonging of South Wales, there is a belonging. There is comfort in our contrariness. In our ‘ugly, lovely, towns’. There is a space for oddness and wildness and the margins of behaviour, a space that South Wales has perhaps forgotten. Thomas saw it. His Wales had space for girls ‘as mad as birds’ and the macabre, doppelgangers of old and young meeting in the October mists, burning children, and women who had lovers made of the eerie ghosts of Blitzed buildings. It could hold paradoxes: the swinging, golden children of Fern Hill starcrossed with the stultified, decaying apple boys of I See the Boys of Summer. It was both ugly, and it was lovely.

Perhaps this is a ramble (Caitlin, you’re saying, there’s no perhaps about it. Wrap it up.). But to me, to come across a text that tells me I can be every weird which way and still be Welsh, that Wales can hold all of those ghosts and oddities as well as its characteristic warmth, created the sense of finally feeling at home. Thomas often left Wales, but inevitably, inevitably drifted back, whether through physicality or through his poems. I hope it will be the same for me. I don’t think, now that we’ve settled our differences and curled up around each other, sleeping in comfortable camaraderie, that we can be easily separated.

Art by Kate Grant

*Dylan Thomas, Reminiscences of a Childhood, in Quite Early One Morning, published by New Directions Publishing Corporation, New York, 1954