Throughout history, the media has always portrayed disability negatively. Among the most recent additions to inadequate disabled representation are SIA’s music, and movies like Me Before You close behind. Whenever a movie or TV show attempts to tackle what it feels like to be disabled or features a character with a disability, the disabled community screams in horror, knowing we will witness something that promotes terrible messages. Scenes from films and television feature backward medical care, wanting to commit suicide because you are stuck in a wheelchair–something that has been shown a thousand times– and the inspirational moment at the end where a person manages to walk, miraculously.

There is hardly a movie, TV show, or comic book character that doesn’t feel like it’s filling some quota on inspiration porn or doom and gloom for the non-disabled. These characters rarely have agency, and the consequences of a lack of bodily autonomy are seldom explored.

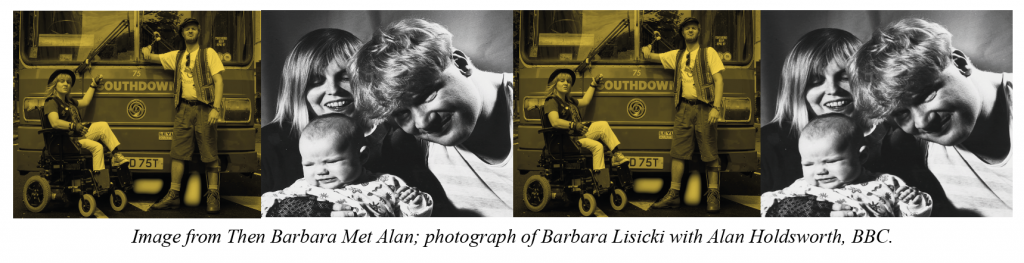

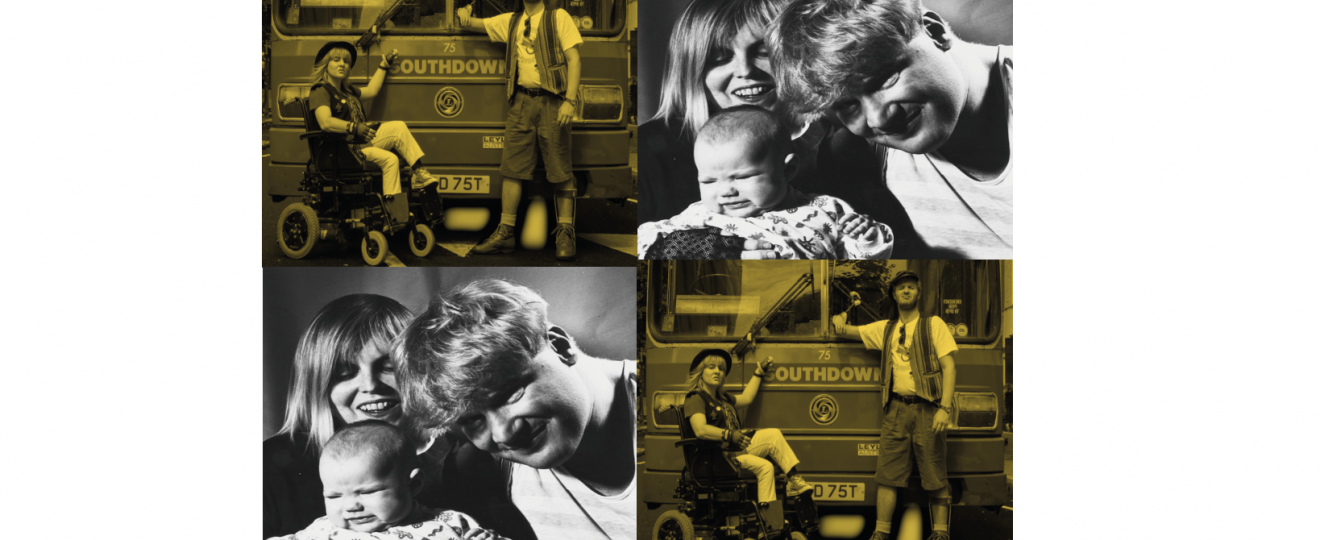

However, Then Barbara Met Alan is the antidote for poor representation of disability on screen and behind the scenes. Then Barbara Met Alan is a biopic penned by Jack Thorne and Genevive Barr. It tells the story of Barbara Lisicki and Alan Holdsworth’s fight for Disabled Civil Rights in the 90s. Years and Years’ Ruth Madeley plays Barbara, and Arthur Hughes plays Alan Holdsworth. On the surface, it might not seem like the most fantastic programme. But for many people like myself, this was a landmark cinematic moment.

As I mentioned before, people with disabilities in the media are treated as weak, infantile, and unable to care for or protect themselves. When you add in other elements such as race or being LGBTQ+, the infantilisation and view that people with disabilities can’t stand up for themselves are worsened.

In Then Barbara Met Alan, there are many examples of these poor characterisations being subverted; in our introduction to Barbara, she is standing and writing ‘piss on pity’ at a bus stop and then transferring back into her chair. This opening scene, Barbara’s handwriting over the bus stop, is excellent for many different reasons. Firstly, it shows us that she is rebellious and doesn’t fit into the box of being the ‘good’ disabled girl: she is fiery and will tell you what’s on her mind; she doesn’t get silenced, she’s gutsy. The scene rejects those quiet, unable-to-look-after-yourself labels the disabled get stuck with, even though independence and interdependence can, and do, co-exist. On top of that, it shows the punk anarchist tone of the biopic from the outset, proving the stereotypes wrong from the beginning and making a fun, dynamic show that brings something new. It is rare to have a disabled woman shown in this way.

Secondly, the scene opposes the non-disabled notion that if you need to use a wheelchair, you are stuck in it constantly, that there is no room for being able to walk. Ambulatory wheelchair users or having a good day are presented as non-existent options– if you can walk for a while, you are labelled a faker and a cheat. The binary labelling between needing a mobility aid and being perfectly abled is very stark and defined. Yet, anyone in the disabled community will tell you that mobility (and disability) has a grey area, where you can walk short distances and need an aid such as a walking stick or a wheelchair. Although this nuance– Barbara’s ability to stand on her own feet despite needing a wheelchair– is much more subtle and more likely to be noticed by those in the community, it still represents the part of the disabled community that is ambulatory mobility aid users, and will make them feel seen. It still plants the seed in non-disabled people’s minds regarding the grey areas of disability.

It’s not only the levels of mobility that are treated as a grey area in the movie, but the relationship between these characters and their disability is too. Much like how non-disabled people often see mobility as black and white, they also see a person’s relationship with their disability as one of two things: it can either be joyous and happy or downright dismal and sad. The lack of nuance in media representations means that the latter tends to be depicted as the standard, leaving little to no room for more joyous portrayals that fight the stereotyped idea of disability.

In Then Barbara Met Alan, this binary, the happy-or-dismal dichotomy, is rejected and substituted with a more realistic and complex depiction of the relationship between the characters and their disabilities. For instance, Alan (Barbara’s partner, in crime and romantically) has a condition that requires him to use Callipers (aids that protect the legs and are more accessible, and provide more movement, than a typical leg brace.) However, throughout the biopic, his condition progresses, and he requires the use of a wheelchair. Instead of showing us a character that is overtly content with relying on a wheelchair, he goes on a journey from being happy and rebellious to being rebellious in the name of self-pity. Providing us with this nuance creates an interesting character arc for the audience to get invested in, without, sticking Alan in the box of being happy or sad regarding his disability. Many will feel that this depiction is more true to life in terms of how they personally process their chronic illnesses– between the highs and the lows there is a neutral state, one in which we usually live. When it comes to Barbara’s character arc, complexity and nuance also underline the evolution of the character: throughout the film, Barbara’s unwillingness to stand up for herself, to fight for a space in the world as an individual with a disability, is substituted by the protagonist’s newfound ambition and drive to become a leader in the fight for disability rights.

Disabled people are typically stereotyped as asexual. We are rarely shown as having sexual needs or relationships, so the romantic relationship between Barbara and Alan that plays out on screen is new. It’s a love story that helped create the movement, and we follow it from its beginning to its bittersweet end. It’s refreshing seeing disabled people have a love story, having sex, and for it not to be some inspiring moment! It also works to help us connect even more to the characters, refusing to deny or attempt to conceal an aspect of their humanity.

Yes, we want representation that presents disability as a more positive thing, but that doesn’t mean the bad stuff that does happen should be sugar-coated. We need stories like Then Barbara met Alan, rebellious tales that show the freedom and hardship within disability and help counter the highly problematic depictions from the media.

Throughout Then Barbara Met Alan, there is footage of protests from the ’90s. Featuring radio reports of D.A.N (Direct Action Network) activists throwing themselves under trains to the demonstrations against the telethon. The combination of the footage with the characters’ gleeful protests against bus stations and the dramatic and wrongful take down of the first bill of disability rights, enhances the punk rock tone of the documentary. Watching these people tear up the system makes me proud. Proud because that was ‘my history.’ It’s the story of people who fought for me to get on a bus and get into mainstream education. Despite not being related in blood, I felt their own trials and tribulations from inaccessible housing to getting on trains– we’ve all felt it.

But it wasn’t just pride and loss I was feeling. Throughout my life, I knew the bare minimum surrounding disability rights. I never knew the full picture of how bad disability rights and accessibility were twenty years ago, and I never knew how we managed to get them to a barely decent stage today. No history class I’ve been in has ever taught a lesson on disabled civil rights. I never knew disabled people had to protest for the stuff I’ve had since birth. In Then Barbara Met Alan I watched these people protest against the telethon hosted by ITV and struggle to be properly arrested because the police cars were inaccessible; I witnessed footage and recreations of activists lying in the middle of the road and making as much noise as possible. Watching all of this felt like some part of me had been found. I knew they weren’t me, but they were ‘me’. Seeing disabled people be rebellious and fight the system, finding out about my history– which had been denied for so long–, felt right!

But the movie isn’t just some biopic paying lip service to a marginalised group. For once, we weren’t being tokenised! During the making of Then Barbara Met Alan, writers Jack Thorne and Genevive Barr created a pressure group called Underlying Health Conditions (UHC). The UHC was designed to address the lack of support and accessibility for disabled creatives in media, and its work is supported by partners 1in4, Creative Diversity Network (CDN), Disabled Artists Networking Community (DANC), and Deaf & Disabled People In TV (DDPTV).

What is more, the movie’s production employed over 30 disabled cast and crew and 55 disabled extras, including activists like Amy Kavanagh, better known as BlondeHistorian on Twitter. This is a record number of disabled people within production, especially given that only 20% of disabled people working in broadcasting were full-time in the past five years, and only 5.2% of off-screen workers and 7.8% of on-screen workers involved in movie or TV productions are disabled. Having such a massive disabled cast is a huge win.

Then Barbara Met Alan is landmark cinema because it takes terrible stereotypes and turns them upside down with an anarchist punk tone to match. It shines a light on a piece of history many (including me) didn’t know existed. Watching Then Barbara Met Alan, for once, I could look at the silver screen and not feel red hot anger or bitter betrayal at what I saw. For once, disability was loud, bright, and defiant. For once, we were allowed to be proud, to ‘Piss on pity’ as the D.A.N network would say. Then Barbara Met Alan is important not just to me but to all the other disabled people out there; it shows what we’re truly capable of.