“She slipped in the shower and cracked her head open. They just found her lying in a pool of her own blood.”

I don’t think I will ever forget Carmen’s face when she told me about the death of her ballet teacher. Her eyes were the size of plates. We must have been around thirteen years old. The funeral was the day after.

The dark realist living inside my brain picked apart the imagery of the event with a combination of aesthetic curiosity and utmost skepticism– on the one hand, a naked vulnerable body, a snap of fate tearing life to shreds, the cliché paleness of the skin almost glowing against a velvet-red puddle, a fragility reminiscent of the broken sweetness depicted in Michelangelo’s Pietà; on the other, the impossible pool of blood, the water still running and washing it down the drain, the fact that she was probably not lying down, but had tumbled over like a ragged doll, that her flesh had hardened not like marble, but into a stiffness too alien to the usual vitality of her body; that the scene was not delicately horrifying, but painstakingly sad and pitiful, too real to be reduced to an imaginary aesthetic composition.

At the time, and still today, I was fascinated by depictions of death, by the intrinsic paradox of portraying someone who is simultaneously both there and not there: if the mind is an essential part of the individual– cogito ergo sum, and all that jazz– how accurate can a representation of the individual be, when the mind, or soul, call it what you will, is not there?

Is the corpse enough to truly embody the character of that who is being depicted?

Now, one could question the importance of the mind in pictorial representations, challenge the idea that something that is by definition not only abstract, but almost ethereal, could be reduced to the physicality of oil on canvas. Is there really a difference between the dead and the living when they only exist two-dimensionally?

Is the mind there when the subject is alive?

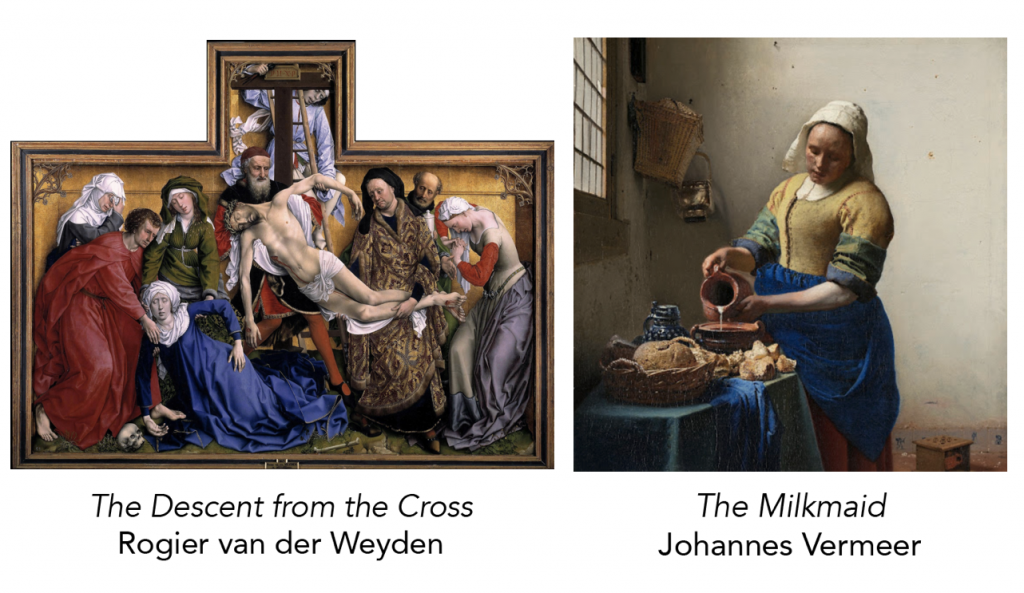

Historically speaking, Art has strived to make sure that it is: even before the technique was improved during the Baroque period, before critics swooned over Rembrandt’s portraits, artists tried to capture the facial expressions of their subjects, to employ them as the mirrors of emotions. If emotions, to whatever degree, are by-products of our thoughts, and our thoughts are, in turn, manifestations of that which we call the mind, then the air of concentration on Vermeer’s Milkmaid’s face, is a latent reflection of the mind pivotal to her being. The peculiar point here is that, following the expression-emotion-thought-mind logic, even dead bodies in paintings can still retain their minds.

While the individual remains dead, the depicted subject never seems to simply be the individual herself, but the act of death subjugating her, the remnants of the individual’s nature still surface through, like tiny daisies blooming through the cracks of a rock. Take van der Weyden’s Descent from the Cross: not only do the transparently visceral reactions present in the living characters’ faces share their inner nature, making their minds almost palpable, but Jesus’s dead visage, the lack of anger and the evident pain, the almost calmness despite the horror of his end, plays the same role. I was and still am fascinated by depictions of death because they illustrate the human obsession with asserting dominance over time– as if it were us who construct time, and not time who defines us.

As if even after death, one could control one’s existence.

Platonists believe– roughly– that time is like an empty container that may be filled up with events and temporal relationships but which, ultimately, exists independently of those things- of us. Are we floating in a container that does not necessitate us? Some days I think we are. Some days I think time is not real at all. I don’t know. Maybe Reductionists– the opposing side of the debate, philosophers can only thrive if they’re arguing against one another– are right, maybe, in an epistemological sense, it’s only reasonable to posit a concept of time that views it as defined by temporal events and relations.

Are we willing the container into existence? Are we, me spilling my chaotic stream of thought into paper, you reading it and wondering why, constructing a tiny figment of time together? That would be poetic.

For the current purposes, we don’t have to worry; regardless of whether Platonists or Reductionists are correct, both views encapsulate a shared quotidian insight. We are made of time. We exist because time is there. We cannot exist outside of it. Think about that for a second: we were born because a microscopic sperm, one out of millions of useless ones that tried and failed, managed to get to the egg and stick its head inside right in time, because the uterus lining hadn’t started breaking down– that time of the month– yet, because the cells that construct a body took the time to grow and develop and form a being, that then lived and died.

We exist because mortality is death and death is time.

We may be floating or constructing the container in its grandest, most abstract sense, but if we bring it down to our very mortal perception, the fact remains that we can’t, not individually, not even collectively, end time.

But time can end us. It does through its very design.

I’m not merely talking about the process of aging– tempus fugit and Rubén Darío’s treasured youth– but about the temporal coincidences that may put a premature end to our lives.

Whenever I cross a road, my mind’s eye sees the me from a parallel universe lying bloody and translucent in the middle of the street. She’s been hit. In her timeline, she took five more seconds than I did to get to the edge of the sidewalk, and the car that hit her turned left slightly more quickly than the one that just slowed down when they saw I was crossing.

Whenever I cross a road I think of premature death.

The death of Carmen’s ballet teacher never traumatized me, but the image stuck to the walls of my mind because it coincided so perfectly with something my mother loved to offhandedly throw into our conversations about life.

“You never know when it’s coming. You could be the healthiest, most precautious person in the entire Universe, and still get into the shower one day and, bam!, you slip, crack your neck and that’s it. Al carajo.”

(That’s how you talk to a child– you remind them of the fragility of their own life.)

In her own blatant and graphic way, my mother was referring to the temporal coincidences I just mentioned: the collision of even the most minute of events that one didn’t even know could be variables at play in the game of survival. The speed at which you get into the shower. How long you let the water pour before you step in. The angle at which you end up falling.

For my mother, the cracking of a neck, and blood all over green shower tiles, symbolized our lack of control over life. Over time. It was her way of telling us that she couldn’t, not really, not fully, keep us safe. That no one could, not even ourselves. That the only condition we accept when we were born was a compromise with death.

The rumble of death is no stranger to society; it covers the ground we tread on and lingers above us even when the sky is clear, forever present in our collective psyche, an inescapable mumble hiding behind our eyelids. Society has accepted the concept of death– we didn’t have a choice– but we haven’t fully grasped the fact that it is untamable. Death does not allow us to get one last say– oh, the beauty of some eminent genius’ last words– not in the almost rehearsed way in which we would like. If someone called Jesus did really die on a cross, his face was not peaceful and pure in the way that van der Weyden envisioned it; it was probably contorted and sweaty and bloody, tense from the pain and unbearable to look at, a mirror of the cruelty inflicted on it, rather than of the grace of some higher being. Death does not allow us to set an exact date, to set a vase of poppies by a table and lie on a bed after 80 years of life, to know that we enjoyed the time that was promised to us. Death only promises death.

Sometimes, incidents like the death of a ballet teacher, the cracking skull against the bathtub, spill the guts of the meaning of death into our hands, forcing us to look at them closely. We shiver and shake and push them away, deciding to call them tragedies, not only because they are, but also because this allows us to treat them as exceptions. As events that do not follow a studied rule.

This is the topography of time we have socially drawn– a straight line on which we can pin-point birth-dates and death-dates, a work-in-progress ideal with the final objective of ensuring total security. No tragedies branching off; only a solid black line.

Security in itself is a fallacy. The progress made in medical technology and care, the developments in automobile safety and food processing, the myriad of changes and improvements that have unfolded over the past century, have reinforced the idea that death can be put on a leash and forced to behave. We have almost grown to believe that we are the masters of time and life, that we can keep on turning the biological hourglass around, that our perfectly modern polished societies have finally arrived at the point of ensuring almost risk-less existences. And, yes, we have managed to look life in the eyes and assert ourselves by curing diseases and providing lasting treatment for others, we have successfully tricked time into allowing us to do things not only faster, but also more safely than before, but we still haven’t been able to control all of the variables that the trinity of life, death and time are playing with.

We never will. We can’t flip over a game we didn’t design.

The problem with the fallacy of security is that it has become a social obsession. Not one we’re proud of, not one we want to admit, but one which trickles down walls and drips from our TV screens. We hand over power to those in the institutions governing us because we want to be safe– and the ultimate epitome of safe is alive. No matter the cost. Covid-19 has thrown the world on its back not only because of our collective fear of dying, but because it has proven that the institutions that swore to protect us, that the shiny faces on our screens and precious welfare states, did not have everything under their control. That they never did.

I’m not claiming we should only blame politicians, and I do not intend to get into the responsibility debate– despite having quite a few thoughts on the matter. I’m merely pointing out that our collective panic, our collective sense of uncertainty, while undeniably warranted, are not new at all.

We had simply buried them under an illusion of control.

We take risks every day, even before Covid-19 made us aware of it: we drive cars and drink alcohol, we use lifts and planes, we eat fast food and exercise less than we should, we have sex with people we don’t know, and put our hands near our mouths before even thinking about the surfaces we’ve touched. We cross the street. We take showers. The uncertainty will always be there. Death will always be there. We cannot force it to be beautiful, we cannot turn it into an option.

But we cannot allow it to define our existence either.

If there is never a vaccine for Covid-19, what will we do? Will we stay inside for years, living in a state of continuous frightful delirium? Will we stop touching our loved ones and sitting on the grass? Will we stop doing everything that defines life within time for the sake of survival?

If there comes a day when we realize that we cannot control Covid-19– will we be able to abandon our desire for security and accept that we never had any power in the fight against time?

Heidegger believed we had forgotten das Sein, that we had forgotten to notice the fact that we’re alive; I wonder if precisely because we are so aware of the fact that we are alive, we have begun to overlook the bigger notion of time. To forget that it does not depend on us, that it never has. That our job– whether we’re Platonists or Reductionists– is to fill it up, not to fear it.

A couple of days ago, I was lying on the grass under the sun, a cigarette between my fingers infusing the air around me. I could discern the shape of my eyelashes against the sky, the optical illusion of discs glowing both too closely and too far away. I thought about death and life. I want to appreciate the beauty of every second and millisecond to the point that I can almost grasp it. I hope Jimena managed to do that. She was Carmen’s ballet teacher. The one who cracked her head open and died.

art by Alcira Hava