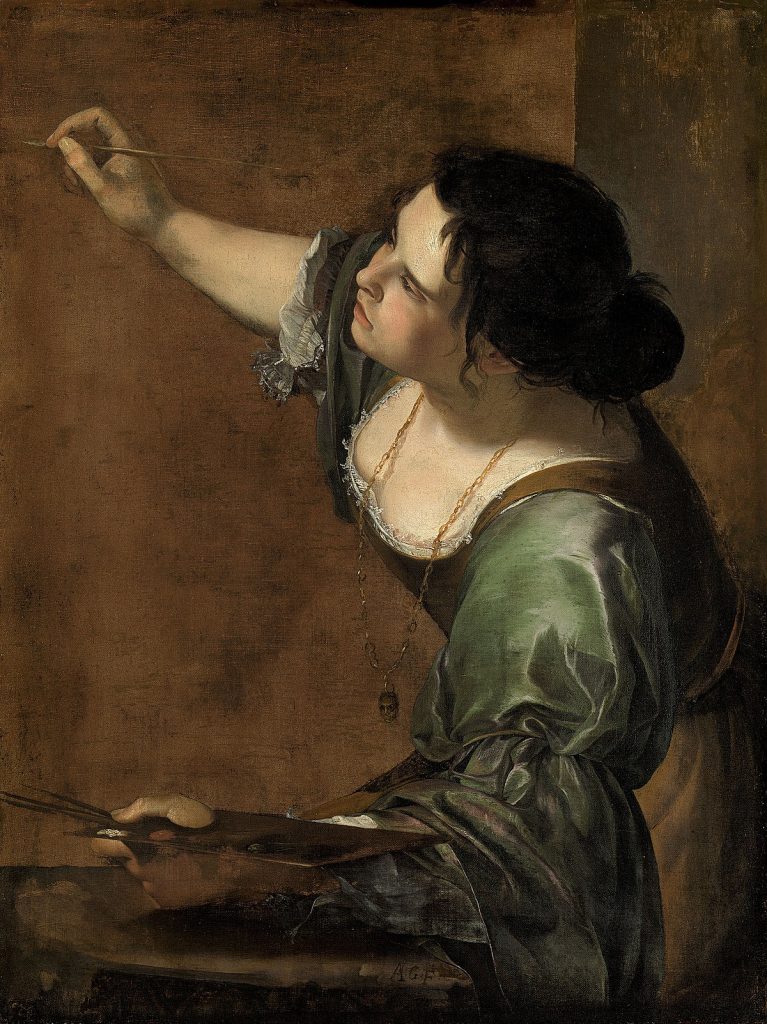

The first time I ever heard of Artemisia Gentileschi was when I saw her artwork– Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting. It was on one of those trips to Hampton Court which, my mother decides, for reasons unknown to the rest of us, is completely and utterly necessary at that given point in time. (As a consequence, I have visited Hampton Court many times throughout my twenty years on this earth, so all the visits by now have blurred more or less into one indistinct memory adaptable to pretty much any anecdote). It must have been raining that day as I found her inside. It would have been in the Cumberland Art Gallery, which displays pieces from the Royal Collection. It is a winding set of rooms by the Haunted Gallery, a very different environment to the bright austerity and openness of an art gallery.

In many ways, it feels sectioned off from reality, a step back to an impossible time where Rembrandt coincides with Gainsborough and Andy Warhol. The painting shows a woman standing at an easel. One hand is raised, the paintbrush poised, a palette in the other as she leans forward into

Artemisia Gentileschi was born in Rome in 1593, the eldest child of

The event that has become the most well-known aspect of her life, however, is the rape that occurred in May 1611. She was assaulted in her own room by Agostino Tassi, a landscapist who often collaborated with her father. In March 1612, Orazio Gentileschi formally accused Tassi of the rape of his daughter, procuring, and the theft of a painting.

What followed was a long legal battle in the Papal courts. During the proceedings, Artemisia was tortured by thumbscrews whilst giving her testimony, for persistence despite pain was meant to demonstrate the validity of her accusation. It could have permanently damaged her

Following the trial, she married Pierantonio Stiattessi, and they moved to Florence by the end of December 1612, in an attempt to escape the scandal that was still resounding across Rome. Once in Rome, Artemisia focused on establishing a successful studio of her own. The arts flourished in Florence and she could also aspire to a position at court. Her first child was born in 1613. By 1615, there is a suggestion of Medici patronage and she became the first woman to be accepted into the Academia del Disegno on July 16, 1616. This is an incredible achievement, especially in the context of the seventeenth century where women were discouraged from having any career at all. Additionally, the art world has a long history of not taking women seriously as professional artists. For example, the Royal Academy in London, founded in 1768, had still only admitted one female student in 1860 and women were barred from life drawing classes until the 1890s. By 1936, the RA had only had three women Academicians.

By 1620, Artemisia and Pierantonio had separated and she left Florence that year. The exact details of the separation arrangement are unknown, but Artemisia was left in full control of her dowry which gave her a degree of financial emancipation. She quickly re-established herself in Rome, gaining cardinals and princes as patrons in a highly competitive market through a combination of artistic skill and business acumen. For the first time in her life, she was completely independent. Her daughters also became artists and worked alongside her as they travelled in order to pursue career opportunities and find new patrons. It was at the court of Charles I of England where she painted Allegory of Painting. In 1641, she moved to Naples where she lived out the rest of her life, painting until the end.

We often focus on the life stories of female artists, perhaps more than we would do if they were men.

Frida Kahlo, for example, has become better known for her mono-browed image, rather than the range of her work. In Gentileschi’s case, we should not make the mistake of letting the rape dominate her narrative. We should not project our own assumptions onto her work, as much as we would want to view a clear relation or feminist message. Her painting of Judith and Holofernes (1614-20), for example, is most likely a rendition of a popular baroque subject rather than an indication of her feelings towards Tassi. Like any 17th century artist, she would have still aimed at pleasing patrons in order to sell her paintings. To view her life’s works in reference to this one event would be a form biographical reductionism that ultimately reiterates Tassi’s temporary dominance over her for eternity.

Instead, what we should see is the work of a practical, successful woman, and above all, a master of her craft.