We all fawned over Blair calling out to Chuck in season 2, episode 1 of Gossip Girl: Three words, eight letters, say it and I’m yours. Our hearts resoundingly broke when he turned away from her, tragically refusing to utter those eight letters for another twenty-four episodes. When he finally let them slip out, our thirteen year old selves rejoiced in the name of true love, of love tortured by linguistic bounds. We sighed woefully and let our hearts ache for Chuck’s inability to transmit those simple words, those words loaded with so much pre-existing meaning, (words we knew Blair deserved to hear!). Of course, at that age, we never stopped to consider what she really meant, or what he really meant, or why, beyond Chuck’s difficult relationship with his cold family (damn Bart Bass!), Chuck found it so hard to say those words, or why, as a collective, it is so difficult for us to say those words.

I love you. Often the hardest words to say in the English language, as well as the most loaded, the most honest, the most vulnerable. The verb, (to) love, is slotted between two pronouns: a direct transmission of a feeling, from one being to another. I, pertaining to nothing other than an individual’s honest emotion, am attempting to translate the weight of those feelings, debatably the most intense human feelings, love, to another being, you. It is one of the most universally understood terms; more than just an emotion, but a developed, curated and sustained feeling. Whether the words I love you are shakily being said to a lover for the first time, or a flippant Love you! said at the end of a phone call to your mother, or a fond Oh, I love her! when talking about Lizzo, it is also the term in the English language that has the most malleability. It covers an extensive range of understandings: romantic connection, familial affection, appreciation for a friend, reverence for an artist, and more. We can appropriately use the term love to express our feeling towards those closest to our heart in our physical reality, and those who have touched our heart in a less physical sense.

Although in the English language we have different ways to redress our expression of affection to make it more elaborate or casual, it still comes down to that single word: love. We take away the I in I love you, to make it more digestible and less intimate, we add an in and with to add vulnerability and ardour to the bold pronouncement I am in love with you (which also implies that there is an answering state of being out of love with you), we transform ‘love’ into an object of endearment when we call much love to our friends. The word love is a shape-shifter, it is a spectrum, it is an umbrella term; a singular word used in an extremely wide variety of contexts. The Second Edition of the 20th volume Oxford English Dictionary contains over 170,000 words in current use and over 47,000 obsolete terms; yet love is our only commonly understood and accepted term to display the heights of our affections.

When au pairing for a family in Madrid this summer, the mother called ¡Te quiero! out to her twin ten-year-old sons as they lopped off to football training. After my enquiring, she explained to me the difference between te quiero (I love you, in a familial or friend sense, more soft and general connotations) and te amo (I love you, in a romantic sense, very strong and intimate connotations). Similarly, in Italian, ti voglio bene is exclusively used to express familial love or love to a friend, whilst ti amo is reserved for romantic love. It struck me that we who share the common tongue of English do not have a way of linguistically differentiating between the expression of those feelings. Those feelings which are inherently different; I think we can safely say the way we feel about our significant other, our mother, and Lizzo are all extremely different, each with their own particular level of intensity, significance and, well, meaning. We only lump them together under the term of love because, due to our linguistic understanding, that is the only term we have ever had to describe them.

As I began the article by saying, I love you is one of the hardest phrases to utter in the English language. Arguably, this is purely because of the human fear of opening up, of possible subsequent rejection, of vulnerability. Yet I can’t help but wonder: have we limited ourselves in the realm of expression by placing so much meaning on one phrase – even, one word? Te quiero and te amo, ti voglio bene and ti amo are employed and embedded into their respective languages, thus providing whole communities and cultures with two different ways to express affection. In English, however, we are confined to the same phrase to be employed in a range in contexts.

It is in human nature to be able to distinguish between passionate love and compassionate love, even if in English we cannot linguistically differentiate between them. Yet, are there implications of limiting our expression of love down to one phrase for our cultural (English-speaking) identity? Although I am not one to advocate for attention to be paid to cultural stereotypes, typically, Spanish and Italian cultures are considered to be more amorous, expressive and affectionate, when held in comparison to that of the English populace, whom are typically thought to be as cold and, at the very least, awkward. Love as a term carries so much weight because of the multitude of intense feelings we have learnt to associate with it; but is this appropriate, or useful? Has our linguistic limitation translated onto how we express love as a culture?

We can plainly see that we are nothing without our language. The way we express ourselves is the basis for our collective identity. We form our community based on shared ideals, and we then develop a common tongue to enact action within this said community; our language is a product of our collective mannerisms. We clearly formulate language in a way that is useful to us, to communicate in a way that makes sense within a particular environment. Vast valleys of differences are blatant between existing languages; the tongue-produced sharp sounds of the Khoisan click language of the African Kalahari Desert, varying from the pin-yin and character combination of the Mandarin Chinese tongue. As a result, all emotions in their behavioural expressions are culturally conditioned. Each culture has their own patterned perspective of love and loving. Thus, there are inconsistencies in how we linguistically express love across the spectrum of languages, as our understandings of love are steeped in distinct cultural circumstances. For example, it has been suggested that the Indonesian conception of love may place more emphasis on yearning and desire than the American conception, perhaps because barriers to consummation are more formidable in Indonesia, which is a mostly Muslim country (Shaver et al. 1991). As so many words and emotions are steeped in the cultural understanding of their particular environment, their translation from one culture to another is near to impossible.

In English, to alleviate some of the weight placed on the statement I love you, we manipulate the same phrase, simplifying it to be more digestible in attempts to break free of the bounds of our linguistic limitations. We break down I love you to luv u and ily as we increasingly become digitalised, to again attempt to make it more bitesize and casual in transmission. Our love language continues to develop with each generation; our parents stare at us blankly, confounded when we tell them we are seeing someone, and a few weeks later that we are now exclusive. We then wince when they ask us when they can meet our boyfriend/girlfriend/partner (Mum, it’s not a relationship!). Love and romance have their own unique place in English-speaking, Western society, and within that, their own unique place in the psyche of each generation. As a result, we have a unique way of expressing these feelings, within the framework of the language available to us, which we use as a vehicle of expression. Perhaps, due to our linguistic limitations, along with an array of societal circumstances unique to our culture, love is more difficult and frightening to communicate in comparison to other cultures.

In the text A Lover’s Discourse, philosopher Roland Barthes attempts to define the phrase I love you. He concludes that it is a blank, meaningless statement, representative of an emotion that holds no bounds. In English, we fill that empty, singular phrase with all we understand to fall under it. We do our best to mould the phrase to communicate a range of affectionate feelings in the most appropriate way. The timelessness of the phrase I love you will prove difficult to budge, and we will continue to redress, undress and overdress the phrase to compensate for our lexical bounds. At least we know are all in the same boat, from Roland Barthes to Chuck Bass.

Three words, eight letters, say it and I’m… I’m linguistically limited.

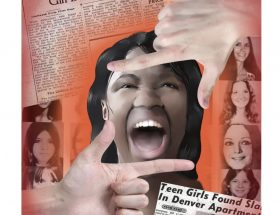

art by Mafer Martinez