We quantify time in many different ways. If you have ever worked a minimum wage job, you will know that, by some standards, an hour is worth £7.70. That’s an hour in the UK – a Lithuanian hour is worth £3.35 (€3.72), an hour in Luxembourg is the most expensive in the world, equalling £10.68 (€11.97), while Liechtenstein have refused to enter into discussions about what price to put on 60 minutes. Our university degrees are quantified by time – a certain number of contact hours a week, twelve weeks a semester, two semesters a year, four years to a course. We quantify distance in time – I’m not sure how far from London I live in miles, but it is about a 2 hour drive, or an hour and a half on the train, or 8 hours in horse and carriage. Same distance, completely different timescales, obviously. In Jane Austen’s time, it was impolite to stay at a formal morning call for more than half an hour – etiquette too can be quantified by time. How long is it rude to spend talking to one person at dinner, or how late to turn up to a party? And, finally, one of the clearest ways we quantify time is through crime – a crime is worth a set number of hours of community service or a certain number of days, or months, or years in prison. But what about fines, I hear you cry! Those aren’t hours spent in prison! This girl is talking nonsense! The minute I’ve already spent reading this twaddle I can quantify as a minute wasted!

I defend my case; I am to tell you that, no!, it is not a minute wasted. Fines are a set amount of money. To earn a set amount of money you must work a set amount of time. Unless, of course, you are so wealthy that fines aren’t truly a form of punishment. It’s worth noting that the transition from corporal punishment to time served in a penal institution occurred around the same time as workers began to be paid by time worked. Angela Davis explains this best in her book Are Prisons Obsolete: ‘the computability of state punishment in terms of time – days, months, years – resonates with the role of labour – time as the basis for computing the value of capitalist commodities.’ And in many ways workers, especially minimum wage workers, particularly those who work for even less in the prison system (prison labour), are seen as commodities, rather than people. To those who are paid by the hour, fines, like prison sentences, are paid by time.

Here I’d like to just make clear that in this article I will be discussing the British and American criminal justice systems, because they heavily influence and inform each other, and because I have not had the same academic or cultural exposure to the systems of other countries.

Back to the point. A significant element of these criminal justice systems is the use of time to punish. Or is it to rehabilitate? Because it is this question, the question at the heart of most debates about penal systems, that really needs to be answered. It should be clear cut; the punishment should fit the crime, the time spent in prison should reflect the size and weight and impact of the criminal activity. And yet it seems that the time that is paid for crimes committed is one of the most arbitrary measures, even more so than the number of minutes you should remain at your coffee date. The first time I properly encountered this concept was in Les Miserables, when Jean Valjean received 19 years in prison for stealing a loaf of bread. Comforted by the fictional nature of this injustice, it wasn’t until the case of Brock Turner, a rapist who only served 3 months in prison, that I realised how far from standardised prison sentences actually are. Your socioeconomic status, gender, race, employment history, the skill of your lawyer; all of these factors can be used as mitigating circumstances, or as a means to heap more barred time onto your back. All of these factors will change how much time your crime is worth. Whether it can result in a life sentence in one country, or be classed as mildly petty in another. In this sense, even geographical location is a ‘mitigating circumstance’.

The weight of a mitigating circumstance is ultimately up to the judge, as is the sentence length. The guidance given to judges in the UK is that the more severe the crime, the less mitigating circumstances should be taken into account. Leaving the sentence length to the discretion of the judge can both work for, and against, the creation of a fair system. On the one hand, it allows for the circumstances of the crime to be taken into account, and the benefits or detrimental effects of a prison sentence on an individual, or their close relatives and community, to be considered. A judge can be made aware of any danger, or absence of, that an individual poses to society. On the other hand, personal judgement allows for personal error, systemic bias, and injustice. One article that surfaced during the height of the publicity surrounding the (continuing) BLM protests showed how three black men convicted of the exact same crime as three comparable white men, by the exact same judge, received over double the length in prison sentence. Systematically, in the second half of the 19th century, women were sentenced to far longer time in prison than men for the same crimes. Because women essentially didn’t have civil rights (no longer being a citizen when they married, and passing over their name and assets to men), their transgressions were expected to be more in the domestic than civil sphere. If they were to have broken a law, this seemed so out of the nature of a ‘good woman’ that they were assumed to be ‘genetically inferior’ and therefore the system wanted them incarcerated for as long as possible during their childbearing years to avoid these ‘inferior’ genes being passed on to their offspring, and producing more delinquents.

On the opposing side to judges’ discretion there are countermeasures such as mandatory minimum sentencing laws. Introduced in America during Regan’s presidency, these aim to establish a minimum sentence length for certain crimes, so that even when considering mitigating circumstances there is still a standardised unit of punishment. The issue is that these standardised units target petty crimes, particularly drug crimes, as they were brought in during the ‘War on Drugs’. For example, drug mandatory minimum sentencing laws are often based on the weight of the drugs seized – a minimum sentence of 5 years must be imposed for the distribution of 5 grams of meth. To contextualise this, 5 grams is roughly 5 days worth of a heavy user’s supply. While there are federal laws on mandatory minimum sentencing for drug offences, there aren’t for other crimes, such as rape. The starting point for a rape sentence is 0 years in prison, and in most states carries a maximum (rather than a minimum) sentence length.

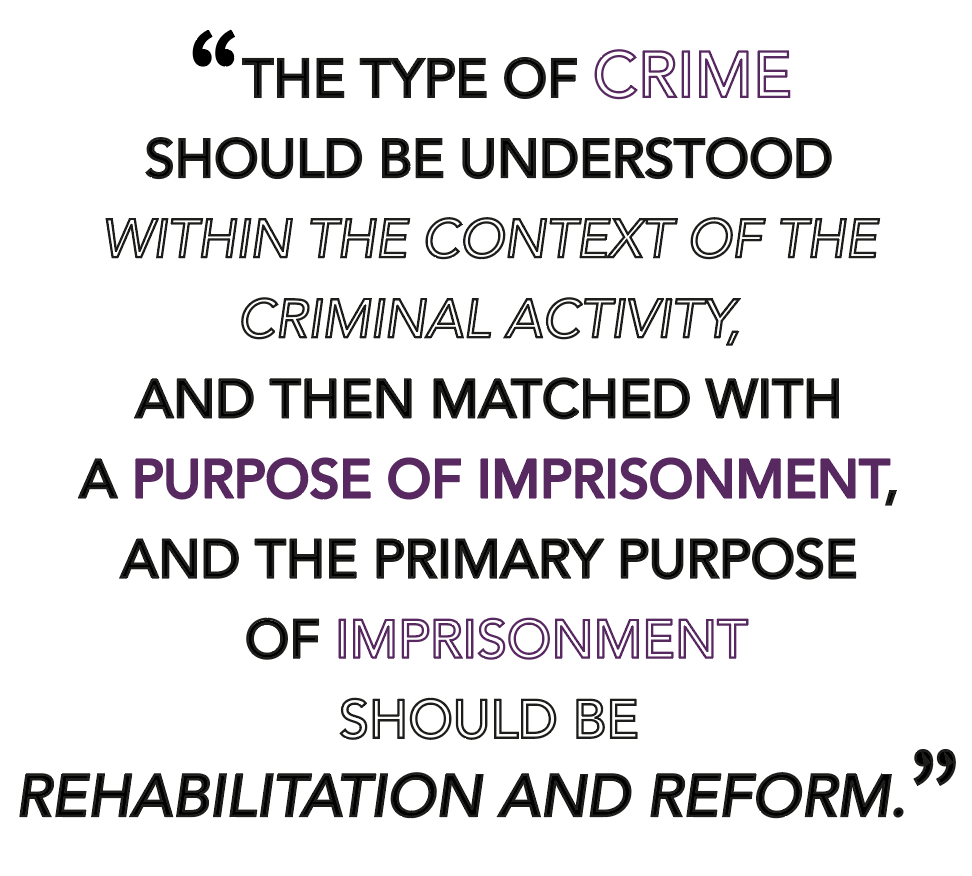

A large part of understanding the calculation of time for crime, or the problems with these calculations, is the lack of clarity about the purpose of imprisonment. Rehabilitation? Punishment? Protecting society? The range of crimes that a person can be convicted for reflects a range of reasons for committing them – people do not rape for the same reason that they embezzle money; they do not sell drugs for the same reasons as those convicted of fraud. The type of crime should be understood within the context of the criminal activity, and then matched with a purpose of imprisonment, and the primary purpose of imprisonment should be rehabilitation and reform.

If the punishment fits the crime, why does time in prison follow ex-convicts throughout their lives? The sentence does not finish once you leave the prison gates, or even if the crime has been legalised –many people are still in prison for dealing marijuana in states in which the drug is now legal, or continue to have the conviction on their record. Ex-convicts are required to flag their status on job applications, are prohibited from applying to or gaining certain jobs, or going to some countries, must check in with probation officers – not unlike Jean Valjean in 18th century France, plagued by his crime long after he was released. If prison is for rehabilitation, why would the prisoner still be a danger to society, a danger to an employer or their neighbour, if they spent the stipulated amount of time in prison? Then again, lifelong identifiers such as the sex offenders list are put in place because some crimes, particularly sexual abuse, are likely to be repeated. This is reflected in US guidelines for sentencing – on a repeat offense of conviction of sexual assault it is recommended that the sentence is doubled.

The punishment following on from a prison sentence that I have the most problem with is the removal of voting rights. Felony disenfranchisement has resulted in 5.3 million people not being able to vote (as of 2008). A removal of voting rights continuing once you have served your sentence is specific to America, and does not happen in the UK. In some states, voting rights are restored after release from prison, in others after parole. In 17 states an ex-convict can only vote after completing probation, and in 11 states ex-convicts must petition the court individually, but can be denied a vote permanently. In terms of time, this elongates the punishment far beyond your prison sentence– not only are you considered less of a citizen, you also have no control over who is in charge, who is making the laws you must live by, therefore affecting your life for long after you walk out the prison gates. As 13th, a documentary about prisons and racial inequality in the US, explains, felony disenfranchisement has a racial dimension, disproportionately impacting people of colour. 7.4% of the African American adult population are banned from voting because of felony convictions; only 1.8% of the rest of the population cannot vote for the same reason. The lifetime likelihood of incarceration for black men is 1 in 3. Considering that only Vermont and Maine allow convicts to vote while incarcerated, and the rest have restrictions even after release, this massively impacts the voting pool, and therefore the people who make decisions about prison policies, police power, laws and criminalisation. From this you can see that even if the time spent in prison is carefully calculated, the time spent being punished is exponentially longer, and very difficult to quantify.

So time is arbitrary, particularly when it comes to imprisonment. This is problematic, seeing that we have based the majority of our criminal justice system on the basis that a certain amount of time corresponds to a specific crime. This is obviously quite a large problem to tackle. I would suggest starting with a clear decision on whether a prison sentence is for punishment, rehabilitation, or protection. Once this is done, more research into the psychology behind law-breaking and the experience of prison would be useful, so as to ascertain exactly what solves a problem, and what aggravates it. For funding, look no further than the police/military budget. Simple.

art by Desiree Finlayson